Mexico | A View from Both Sides: Stories of Migration by Photographer Encarni Pindado

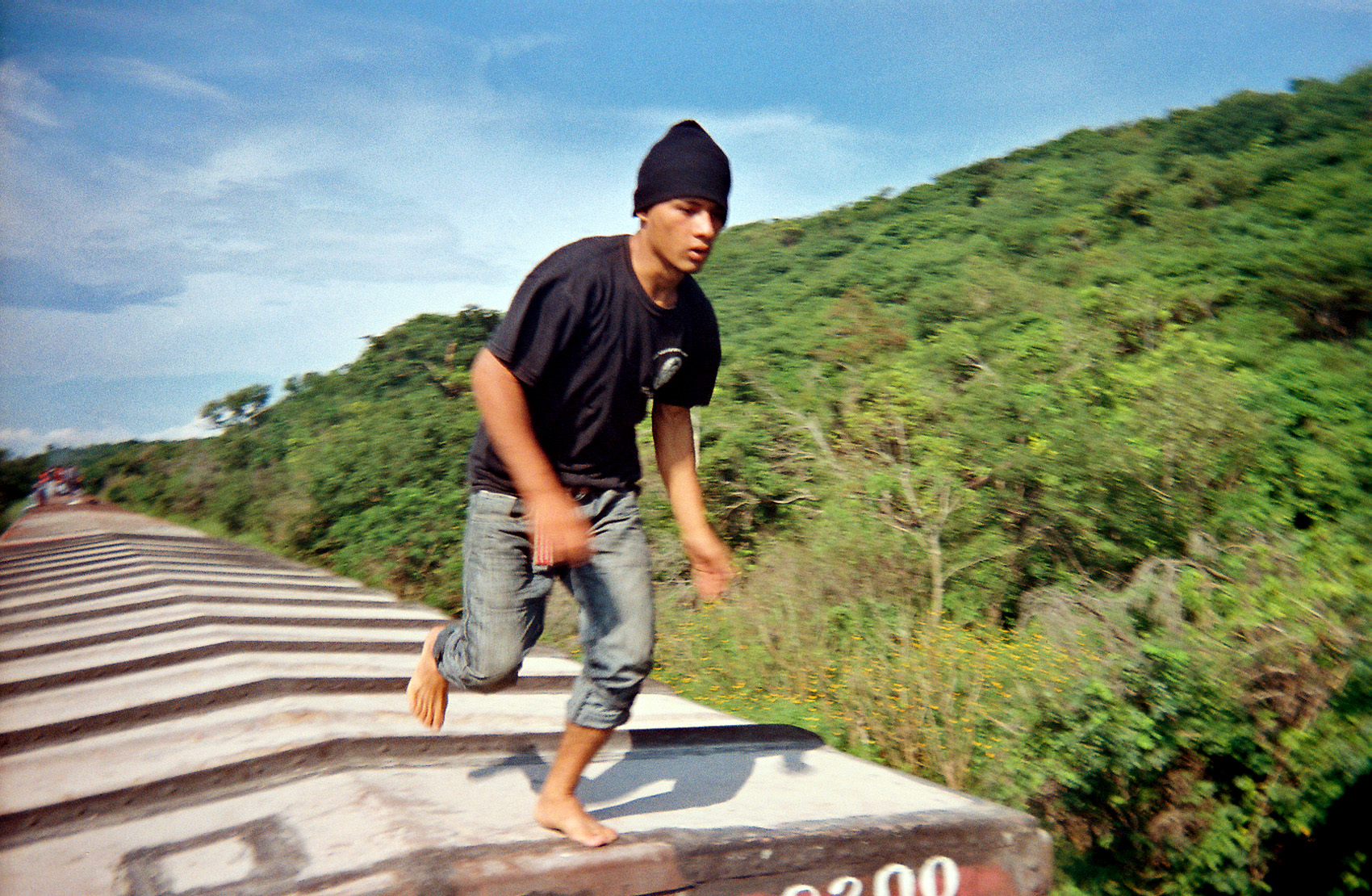

A young man hitches a ride on top of a cargo train from Arriaga, Chiapas to Ixtepec, Oaxaca in southern Mexico. In addition to the risk of falling off the train (amputations and death are common), gangs frequently extort migrants and charge them $100 to ride. They face threats of being thrown off the train, kidnapped, raped or trafficked if they do not pay. Photo by MigraZoom participant.

BY ASMARA PELUPESSY | THE IMMIGRANT ISSUE | SPRING, 2014

Photographer Encarni Pindado has been living and working in Mexico for the past three years, covering social issues with a focus on gender and migration. Journeying alongside migrants and collaborating with shelters, local non-governmental organizations, human rights activists and other journalists, she has gained the trust and access to tell integrated, truthful stories about migration.

Pindado is especially passionate about confronting the issue of violence as experienced by women migrants. As she explained to me during a recent Skype conversation, while the top forces driving people to leave their homelands are often economic and environmental, for the women she documents, it is violence—whether structural, cultural and/or physical—that shapes both their decision to immigrate and their experiences of migration.

Stories of migration have been reported in the media from many different angles, but rarely told by the migrants themselves.

Every year, over 400,000 people cross Mexico’s southern border. That they make this journey northward to Mexico despite the extreme economic costs, physical demands and dangers, gives us some indication of the conditions in their home countries, their vigorous ambition, desire, strength and capacity to dream, and the lure of U.S. living standards. These men and women are profoundly vulnerable to the increasing violence and impunity of Mexico’s narco-trafficking networks. On what is already a dangerous, arduous route in which people ride on top of cargo trains known as La Bestia (The Beast), they are forced to navigate and survive the thriving business that organized crime has made out of migration.

Recently, Pindado has expanded her practice—photographing migrants as well as encouraging them to represent their own experiences of migration. As Pindado shared with me, she was motivated by the fact that stories of migration “. . . have been reported in the media from many different angles, but rarely told by the migrants themselves. There is a gap in knowledge about what migrants actually experience, as well as a stigma and misconception about migrants, especially in the communities they have to cross through.”

.

A Guatemalan migrant rests in the Hermanos en el Camino shelter in Ixtepec, Oaxaca. Before embarking on her journey she has used a contraceptive injection known in Central America as ‘the anti-Mexico vaccine.’ Many women prepare themselves for the high likelihood that they will be raped during their journey. Sometimes women traveling alone will choose a male companion for the journey and exchange sex for protection. © Encarni Pindado

A Guatemalan migrant rests in the Hermanos en el Camino shelter in Ixtepec, Oaxaca. Before embarking on her journey she has used a contraceptive injection known in Central America as ‘the anti-Mexico vaccine.’ Many women prepare themselves for the high likelihood that they will be raped during their journey. Sometimes women traveling alone will choose a male companion for the journey and exchange sex for protection. © Encarni Pindado

.

A Central American couple in a migrant shelter in Lecheria, El Estado de Mexico. The woman pictured is seven months pregnant. Some pregnant women migrate in hopes that their child will be born in the U.S. This shelter was later closed by authorities due to pressure from local residents accusing migrants of criminal behavior. © Encarni Pindado

A Central American couple in a migrant shelter in Lecheria, El Estado de Mexico. The woman pictured is seven months pregnant. Some pregnant women migrate in hopes that their child will be born in the U.S. This shelter was later closed by authorities due to pressure from local residents accusing migrants of criminal behavior. © Encarni Pindado

.

In July of 2013, Encarni founded the participatory photography project MigraZoom in which migrants and members of the local communities are given disposable cameras and free photography workshops to tell their own stories. The United Nations Development Program funded the first phase of the project.

MigraZoom launched at the Mexican-Guatemalan border in Tecun Uman and covered the first 400km of the journey north, through Chiapas. The photos reveal personal and intimate views. Migrants photograph in areas simply too dangerous for journalists to cover. In the first leg of the journey, many of the photos express hopefulness and optimism—a sense of adventure and youthful invincibility. While the participants record positive memories, MigraZoom has also heard stories of struggle and loss as these men and women continue towards the U.S.

They take take their cameras with them as they travel, dropping off the exposed cameras at the next shelter where they stop. There, MigraZoom picks them up, scans the film, gives local participants prints of their own photos, and emails migrants the images whenever possible. The MigraZoom photos continue on their own journeys through exhibitions and slide shows at cultural institutions and migration forums, including the Mexican Senate and Movimiento Migrante Mesoamericano’s caravan of Central American mothers of missing migrants.

.

A 13-year-old boy traveling with his 19-year-old brother (not pictured) from Tapachula to Arriaga, Chiapas. In order to avoid checkpoints, migrants walk from Mexico’s southern border to Arriaga where they catch cargo trains North. The roads and fields they pass through are sites of regular attacks by organized crime and migration authorities. MigraZoom was later told that the brothers were extorted on the cargo train and were unable to pay the demanded fee. The older brother was thrown from the train and it is not known what happened to this boy. Photo by MigraZoom participant.

A 13-year-old boy traveling with his 19-year-old brother (not pictured) from Tapachula to Arriaga, Chiapas. In order to avoid checkpoints, migrants walk from Mexico’s southern border to Arriaga where they catch cargo trains North. The roads and fields they pass through are sites of regular attacks by organized crime and migration authorities. MigraZoom was later told that the brothers were extorted on the cargo train and were unable to pay the demanded fee. The older brother was thrown from the train and it is not known what happened to this boy. Photo by MigraZoom participant.

.

View of the Suchiate River from Tecun Uman, Guatemala, at the border with Mexico. The photograph was made by one of the rafters who transports migrants, locals and cargo across the river. Rafters are stigmatized by their community and sometimes viewed as criminals for carrying migrants and illegal goods. However, in this impoverished community, this is one of few sources of income.

View of the Suchiate River from Tecun Uman, Guatemala, at the border with Mexico. The photograph was made by one of the rafters who transports migrants, locals and cargo across the river. Rafters are stigmatized by their community and sometimes viewed as criminals for carrying migrants and illegal goods. However, in this impoverished community, this is one of few sources of income.

.

The images made by migrants and community members who experience migration as part of their daily lives add an essential layer to the visual representation of migration’s complexities. While the MigraZoom photographs are created principally to engage their makers in the process of self-representation, dialogue and exchange, these images are also valuable documents. Like all photographs, they record not simply what is in front of the camera, but also reflect the perspectives of those behind the lens. As global and timeless as the story of migration may be, each photo invites us to encounter a unique story, a particular life, a singular moment and a subjective feeling.

Exhibitions of the MigraZoom photographs are planned for Mexico City and Tapachula, Chiapas. The project hopes to raise funds to continue MigraZoom all the way to the U.S. border.

♦

Asmara Pelupessy is co-editor of the book UNFIXED: Photography and Postcolonial Perspectives in Contemporary Art. She was researcher and producer for Via PanAm, Dutch photojournalist Kadir van Lohuizen’s yearlong project on migration in the Americas. She also worked as Archive Researcher at World Press Photo. Pelupessy received her MA in Photographic Studies from the University of Leiden (NL) and holds a BA from University of California at Berkeley (US) with an interdisciplinary major in the Social History of Photography.

Asmara Pelupessy is co-editor of the book UNFIXED: Photography and Postcolonial Perspectives in Contemporary Art. She was researcher and producer for Via PanAm, Dutch photojournalist Kadir van Lohuizen’s yearlong project on migration in the Americas. She also worked as Archive Researcher at World Press Photo. Pelupessy received her MA in Photographic Studies from the University of Leiden (NL) and holds a BA from University of California at Berkeley (US) with an interdisciplinary major in the Social History of Photography.

Twitter: @AsmaraPelu

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change. OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.