Guyana | Three Image-Makers Envision Home

"Virtual Exiles: Going for Gold." Roshini Kempadoo. 2000

By Nalini Mohabir

Roshini Kempadoo, Keisha Scarville, and Sandra Brewster are women with roots in Guyana who currently reside outside of the country’s geographical borders, though not its imagined ones. Their images remind us that we are all situated – in relation to particular peoples, places, and histories that walk with us. This is the fact of the diaspora. Taken together, the work of these artists reflects the ghostly presences that linger over the concept of “home” for the Guyanese diaspora. For all (formerly) colonized and racialized diasporas, home remains a very complicated project.

Roshini Kempadoo

Born in Guyana, Roshini Kempadoo is a London-based photographer, digital image artist, and academic who works across archives and contemporary digital photography. In light of the recent revelation of troubling migrated archives spirited away to London from decolonizing countries including Guyana, it’s timely to revisit two images from her Virtual Exiles (2000) series. As Kempadoo states, this series is about migration: “the experiences of individuals who have left their country of origin and who are now at ” ‘home’ in another.” These images reflect the relative silence of the stories left behind, experiences little known, imaged or imagined in their new ‘homes.’

At first glance, Going for Gold (pictured at the top) is an image of a solitary fisherman in a wooden boat along Guyana’s waters. Upon closer gaze, the fisherman leans his head onto his hand, a gesture of deep thought, weariness, or perhaps sorrow. Our own certainty about the tranquility of the image is troubled. As our eyes refocus in search of the source of his emotions, we are drawn to the shadows upon the water. Gradually the curve of a shoulder, the crook of a neck, the torso with a long scar down the middle becomes visible underneath the waves: it is a dead body upon which he floats.

Nobel laureate Derek Walcott penned the poem “The Sea is History” (1979), which suggests that the sea is not emptied of history:”Where are your monuments, battles, martyrs?/ Where is your tribal memory? Sirs,/ in that gray vault. The sea. The sea.” The sea, as Walcott writes, is a site of mourning. Soaked into the sediments of the ocean floor are layers of history, from the bodies of enslaved Africans thrown overboard, to the faded dreams of anti-colonial struggles, to this unknown death in the recent past. This is a history unwritten, but nonetheless capable of being read in the seascape.

The second image of Kempadoo’s provides a more precise dating of the period that concerns her migration sensibilities. In Frontlines/Backyard (pictured above) we see the unmistakable image of an older Indo-Caribbean woman from the country-side (her dress, hair, and stance places her). Her back is turned to us; she is seemingly absorbed by a ghostly newspaper image transposed onto a wooden fence. Following her guide, our eyes rest upon the headlines. The following words are faintly visible: “PNC PLANS FOR…UNCHANGED. Call to preserve peace…need for vigilance. …RC priest dies after scuffle. …3 charged with setting fire to office of PNC General Secretary. …Cuba Vice President arrives.” Kempadoo take us back to July, 1979, a period of heightened intimidation by an authoritarian state under PNC rule (the People’s National Congress, led by Forbes Burnham), and resistance led by activist groups such as the WPA (Working People’s Alliance, of which Walter Rodney was a leading member).

“Times of tragedy and trauma in the wake of independence continue to disturb a Guyanese consciousness, whether at home or away.”

The “3 charged with setting fire to office of PNC General Secretary” were Walter Rodney, Rupert Roopnarine, and Dr. Omawale. The ‘RC (Roman Catholic ) priest’ was Father Bernard Drake, who photographed the WPA protest around the arson charges. In the midst of that act, he was stabbed to death by a paramilitary group working at the behest of the government. In a recent reflection upon these tumultuous events, Rupert Roopnarine (2010) recalled that 1979 was supposed to be the “Year of the Turn.” The “Year of the Turn,” so named by the WPA, was also their nod to anti-colonial resistance captured by poet Martin Carter in This is the Dark Time, My Love: “This is the dark time, my love/ It is the season of oppression, dark metal, and tears/ It is the festival of guns, the carnival of misery/Everywhere the faces of men are strained and anxious.” Times of tragedy and trauma in the wake of independence continue to disturb a Guyanese consciousness, whether at home or away.

Keisha Scarville

Keisha Scarville hails from Brooklyn, New York and her photography weaves the theme of memory through the intimate familiarity of family and everyday objects. The selected images here are taken from the series Many Waters. The title of the series refers to the Amerindian meaning of “Guyana”: The Land of Many Waters. Many Waters is also a reflection of a trip to Guyana undertaken with her mother. As she writes: “I wanted to capture the tension of returning to a place that was once ‘home’ and then through distance and time, becomes unfamiliar territory.”

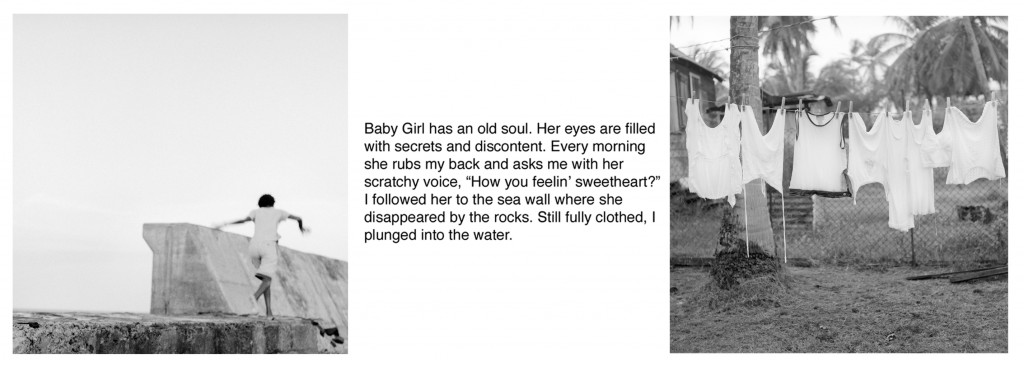

The greyscale images of Baby Girl/Clothing Line comprise a diptych accompanied by text. On the left we presumably see “Baby Girl” running barefoot along Guyana’s sea wall. The figure is blurred against the concrete of the sea wall and infinite sky. The sea wall is an iconic structure that snakes along the coast. Dating from the Dutch colonial era, it protects Guyana’s coast from the encroaching Atlantic. In Georgetown, the sea wall is often alive with joggers before dusk, and lovers afterwards. “Baby girl,” a term of endearment, together with the accompanying text, “Every morning she rubs my back…how you feelin’ sweetheart?” alludes to the enchantment of lovers. As the in-between text describes, the narrator follows Baby Girl out to the sea wall and plunges into the water.

As we are told that ‘Baby Girl’ is an old soul, the text and accompanied imagery suggest the Guyanese folkloric figure of Wata Mama, a female enchantress stemming from African legend who lures men underwater to their death. According to legend, in the rush to water Wata Mama often leaves objects of domesticity (such as a comb) behind. This is a legend, uprooted, transported, merged with Amerindian mythologies, and transformed in the ‘new world.’ It is a re-imagining that forms the connective tissue between the two images, where to the right of the text, we see a yard with washing hanging in the still breeze, apparently left behind in the irresistible pull towards the ocean, the only home Wata Mama knows.

Tombstones is an image of a multi-denominational Guyanese cemetery; a neem tree and Muslim minarets are visible in the periphery. Overgrown grass, weeds, and ‘bruk up’ stone in the foreground suggests an absence of the living to tenderly care for the dead. Where are the relatives and descendants? Where have they gone? This is the photographic story of migration — of departure, and return only for funerals, possibly one’s own — faced by all Guyanese, whether Christian, Hindu, or Muslim. The term ‘Creole’ in Guyana referred to anyone who was born locally, a ‘son of the soil’ (Walter Rodney, 1981). Therefore, this is an image of belonging, as well; an image of spiritual return to the land, felt in the bones. Under the vastness of sky and land that is this land of the Caribbean located on the South American mainland, a deeper pull to memory (personal, family, and history) lies buried.

Tombstones is an image of a multi-denominational Guyanese cemetery; a neem tree and Muslim minarets are visible in the periphery. Overgrown grass, weeds, and ‘bruk up’ stone in the foreground suggests an absence of the living to tenderly care for the dead. Where are the relatives and descendants? Where have they gone? This is the photographic story of migration — of departure, and return only for funerals, possibly one’s own — faced by all Guyanese, whether Christian, Hindu, or Muslim. The term ‘Creole’ in Guyana referred to anyone who was born locally, a ‘son of the soil’ (Walter Rodney, 1981). Therefore, this is an image of belonging, as well; an image of spiritual return to the land, felt in the bones. Under the vastness of sky and land that is this land of the Caribbean located on the South American mainland, a deeper pull to memory (personal, family, and history) lies buried.

Sandra Brewster

Toronto is home to one of the largest, oldest, and most dynamic Caribbean diasporas in North America. Sandra Brewster, born in Toronto, is a multi-media artist whose work references photographs, story-telling, and portraiture as it relates to people of African descent who left their countries of origin during the 1960s and 70s, and the generations that followed. Like the other artists discussed here, she too has specifically engaged with Guyana. However, to switch our focus to the contemporary moment, and to her particular location in Canada (a site that is often overlooked in depictions of the Black Atlantic), we draw attention to two images from her series entitled Little Boy (2010).

In her artist statement, Brewster describes an encounter with a youth (not a child, not yet an adult) on the subway. With emphasis on ‘the look,’ she noted “he entered the subway train looking angry – as if someone had done him some serious wrong.”

The images selected from the Little Boy series reflect her ongoing interest in, and sensitivity to, the stance of Black bodies in Canadian spaces (some of the figures are similar to those featured in her series, Strip, 2008). In this series, she explores the ‘hard’ stance (mask of toughness) during a volatile and vulnerable transition in the lives of “little boys,” a time when guidance is still needed, to navigate negative influences, as well as the dominant gaze. Young Black men barely out of childhood, are heavily policed; they embody an unspecified threat through difference. Thus, through the look of these youth, Brewster draws attention to their simply being — and the way they have to be — to survive the narratives projected onto their bodies. The body language of her figures might be seen as a particular form of Black hetero-masculinities captured by an oppositional stance. However, Brewster’s work also challenges the viewer to look beyond a standard narrative through the play between light and shade.

“…through the look of these youth, Brewster draws attention to their simply being — and the way they have to be — to survive the narratives projected onto their bodies.”

Little Boy 1 depicts two men drawn in charcoal, against a silk screen print of soccer balls. There is a sense of vigilance against tragedy or threat; one figure, seated, looks the other way, the other, standing, faces the viewer. The seated figure wears a kango cap, and the other baggy jeans, clothing not seen as ‘respectable’ in the mainstream. This is a typical image of hanging out on a street corner; perhaps conjuring street-level soldiers. However, the soccer ball offers a different reading. The soccer ball, rather than the more common symbolism of the basketball (at least within urban North America) suggests a leisure activity of Caribbean immigrants, and the normal ordinariness of an immigrant childhood. Hence, the tension in this image rests between being the subject of one’s own story, or the object of suspicion by media, police, and heightened public attention. Underneath these seemingly objectified figures paired with innocuous symbols of childhood play, Brewster prods the viewer to think about how we internalize, or are implicated in, the racialized images of young Black men that deny their vulnerabilities.

Little Boy 3 portrays three male figures drawn in charcoal, against a silk screen print of teddy bears with “I love you” on their front. The figure in the distance, wearing a baggy sweatshirt has his back turned to us. Another, to the left, stands with his arms crossed against his chest, and to the right is a faceless figure wearing a hooded garment. The teddy bears poke through the transparent light of his body. The teddy bears signify childhood innocence, the very opposite of aggression. Within the history of the Afro-Caribbean experience in ‘the new world,’ the teddy bears are also a reminder of a longer history of childhood denied that can be traced back to slavery, and forwarded to the continuing societal fear of young Black men (as evidenced by the disproportionate rate of police stops faced in Toronto). At the risk of subordinating tenderness, the intersecting realities of age, race, gender, and history continue to press upon the ‘coming of age’ Black experience in Toronto, pushing some into a defiant pose. But to the young man on the subway, Brewster offered “a broad smile,” and in response: “His lips almost smiled … He started to fidget … Unable to maintain his image of the toughest guy in the room… His eyes became tender.”

Little Boy 3 portrays three male figures drawn in charcoal, against a silk screen print of teddy bears with “I love you” on their front. The figure in the distance, wearing a baggy sweatshirt has his back turned to us. Another, to the left, stands with his arms crossed against his chest, and to the right is a faceless figure wearing a hooded garment. The teddy bears poke through the transparent light of his body. The teddy bears signify childhood innocence, the very opposite of aggression. Within the history of the Afro-Caribbean experience in ‘the new world,’ the teddy bears are also a reminder of a longer history of childhood denied that can be traced back to slavery, and forwarded to the continuing societal fear of young Black men (as evidenced by the disproportionate rate of police stops faced in Toronto). At the risk of subordinating tenderness, the intersecting realities of age, race, gender, and history continue to press upon the ‘coming of age’ Black experience in Toronto, pushing some into a defiant pose. But to the young man on the subway, Brewster offered “a broad smile,” and in response: “His lips almost smiled … He started to fidget … Unable to maintain his image of the toughest guy in the room… His eyes became tender.”

Nalini Mohabir currently lives in Toronto, Canada. She received a Ph.D. degree in Geography in 2012. Prior to graduate studies, she worked in community development in various cities such as Toronto, Denver, and Cape Town, South Africa, with an emphasis on fostering spaces of dialogue where we can ‘be together,’ while acknowledging differences in history, power, and privilege that have accumulated advantage for some, and disadvantage for others.

____________________________________

Of Note Magazine is a sponsored organization of Artspire, a program of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.