Montana Ray: The Concrete Poems of (guns & butter)

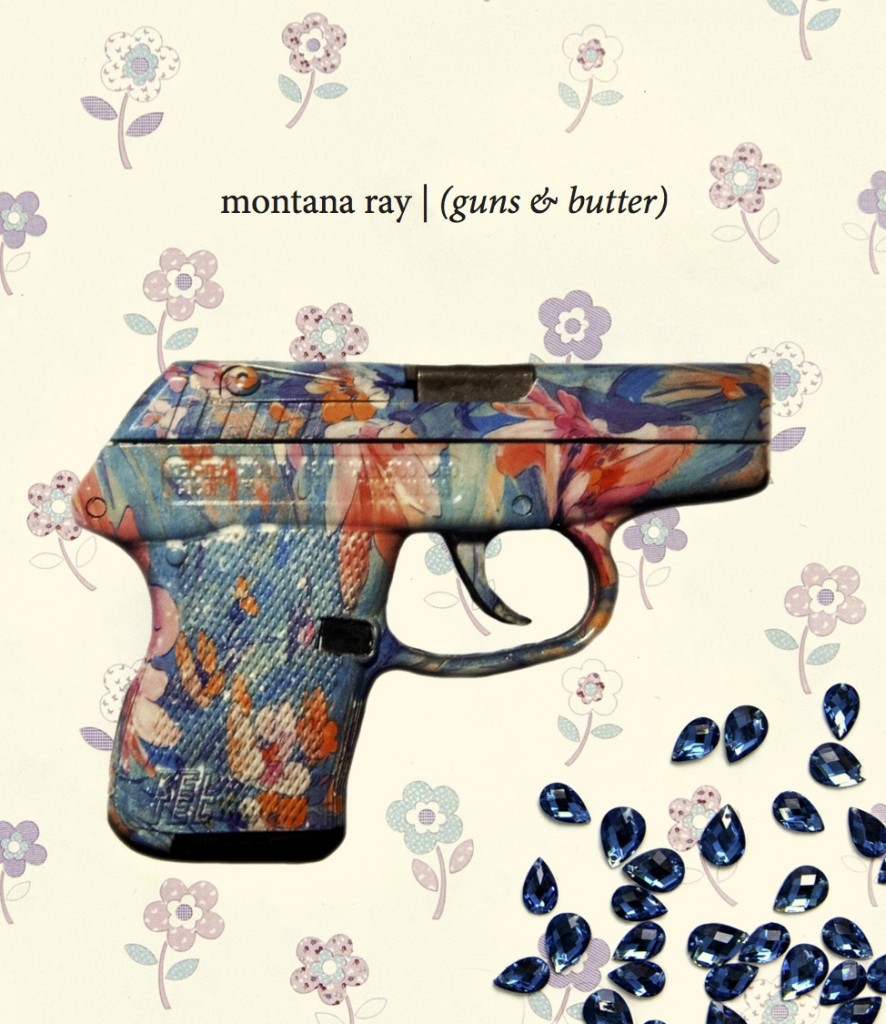

Cover of (guns & butter), 2015. Artwork by Dawn Whitmore. Courtesy of the artist.

I’ve never owned a gun and never will. They scare me. I’ve had friends who, since the election, say we should arm ourselves. But it’s like that Chekhov cliché—you bring a gun on stage, it must go off. — Montana Ray

BY STACY PARKER LE MELLE | THE GUN ISSUE | SUMMER 2017

Born in 1974, I was too young to watch Blaxploitation films first run but soon I’d admire the images of Black goddesses and guns and everything we were supposed to want in America—the movie poster iconography of sex, power, and money. Look at Johnnie Hill on that poster for Velvet Smooth. Pam Grier cradling her sawed-off shotgun on the poster for Coffy. They looked strong. They looked hot. They looked like they didn’t take mess from anyone. With a gun, you could believe you were finally free. As long as you were never overpowered by an opponent. As long as the Feds didn’t show up armed to the teeth.

In America, notions of gun rights, and merits, are fiercely debated. I live in Harlem in 2017. In the 1980s, drug-trade crime overwhelmed these streets. Today, I feel a strong level of personal safety. I close my green steel door and believe I’ve protected myself and my family from the outside world. We don’t keep guns. We think they make us unsafe. Yet I’m aware that personal well-being is just that—personal. I wish all of my neighbors would melt down their guns but I don’t know what trauma they can’t bear to repeat. What promise the gun whispers when it’s hidden in the drawer.

The Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence reports that in 2010 there were 31,076 Americans who lost their lives to gun-involved homicides, suicides, and unintentional shootings, per CDC statistics. That year we lost three Americans per hour to gun violence. In 2011, according to FBI data presented by Everytown for Gun Safety, 53% of women murdered with guns in the U.S. were killed by intimate partners or family members. Many gun-owners carry guns to fend off attackers, but the Gun Violence Archive statistics as presented by Armed with Reason show that in 2014 there were fewer than 1600 verified defensive gun uses. Guns promise to protect us from aggressors but the statistics show we have a much higher chance of being hurt by guns than being helped by them.

The first time I see poet Montana Ray’s book (guns & butter) I am struck by the cover art Fresh Bouquet by Dawn Whitmore. For me, it is a new iconography with its hand-painted pistol on a flower print-like wallpaper in a mother’s kitchen. In the corner, a handful of decorative blue gems. Is this the haul from a woman’s heist? I look again. What’s the takeaway from this feminized tableau? Can a woman ever get out ahead carrying death on her hip?

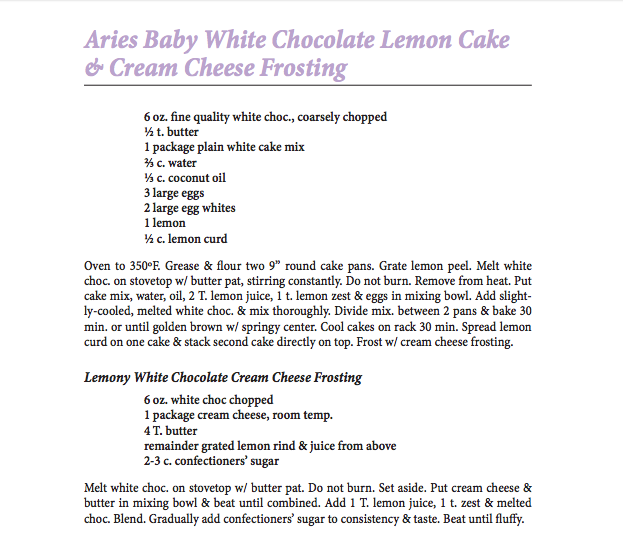

The pretty gun on the cover of (guns & butter) seduces you to open the book and encounter more guns. But this time, they are poems shaped as guns, and they are complicated works of art. In this collection, Montana Ray creates both literary and visual art with her concrete poems, a form of poetry where the shape of words on the page construct meaning. “Concrete poetry is about machinery,” says Ray in an interview. “The founders of the concrete poetry movement in Brazil sought to create poem machines.” Ray’s concrete poems form pistols, and pop-guns, and upside-down guns if you count the recipes she includes as text. “The form allows you to work out what you’re trying to say,” says Ray. Montana Ray’s gun poems contain many truths at once, especially when juxtaposed to her printed recipes for white chocolate banana bread, a chorizo and egg dish, and a rum cocktail—the “butter” of the book, sustenance that can be nourishing or bloating, depending on your intake.

Ray’s first inspiration for a gun-shaped concrete poem came from a man’s gun-shaped tattoo. “He was a crush of mine who worked a tattoo parlor near my house. He’d just gotten a new tattoo of Billy the Kid’s gun from 1873. I kept seeing reproductions of guns. In artwork, in art world merchandise, in pop culture” says Ray. Poet Cathy Park Hong encouraged her form experiment, noting how the parenthesis around words and phrases made them look like the gun’s bullets.

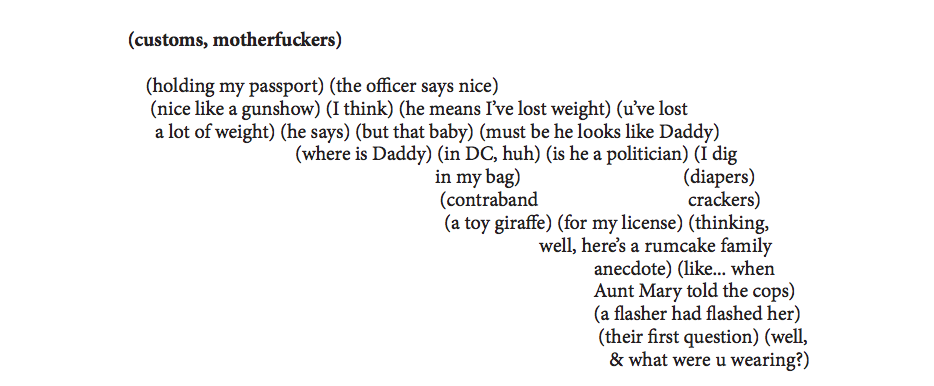

© Montana Ray, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

In the pistol poem “(customs, motherfuckers),” the encounter between a border control agent and the female persona of the poem is fraught with all that can go wrong when we’re questioned by agents of the state: “(holding my passport) (the officer says nice) (nice like a gunshow).” This man can keep her out of her own country if he chooses. This man can detain her. There’s a question of the “(contraband crackers)” in her bag, but this doesn’t concern him. He’s commenting on her picture, as if he has the right. He’s commenting on her child, “(must be he looks like Daddy),” and then makes an aside “(in DC, huh) (is he a politician)” that can be snide while probing to see if there’s a more powerful man who’ll retaliate. He can take these liberties because he holds not just her passport but the power in that moment. His border control is border aggression.

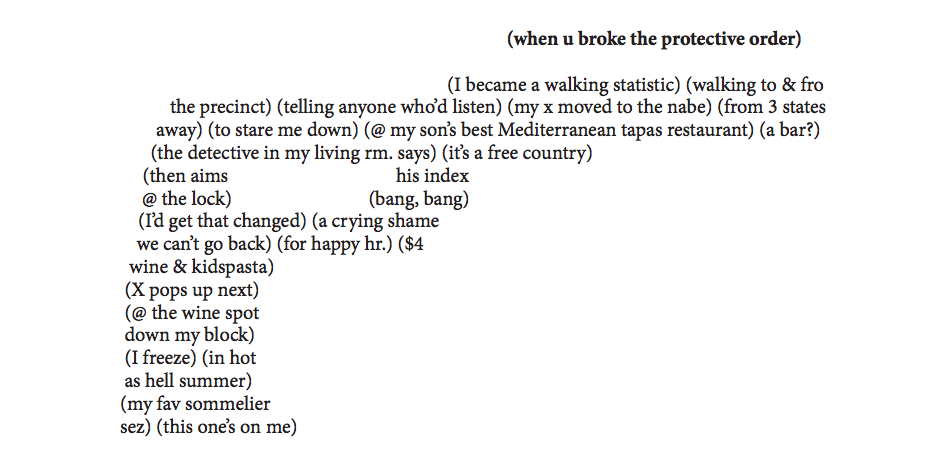

We’ve all grown up fearing the aggressive stranger. But too many of us know the pain of family violence. In Ray’s pistol poem “(when u broke the protective order),” we feel her anxiety when “(my x moved to the nabe) (from 3 states away)” and her helpless rage when “(the detective in my living rm. says) (it’s a free country)” then tells her she should get her locks changed. How her ex shows up at her regular haunts. He’s a ghost now. A promise of violence.

© Montana Ray, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

“I was stalked by an ex-partner for four years. An education in paranoia: is this happening, or not happening?” says Ray. “I had to report each incident to cops, who had guns, who didn’t make me feel safe or protected. One time when I was making a report, the cop asked for my friend’s phone number. I mean you have to swim in that. That’s how you get everything documented.”

And therein lies much of the tension within the poem machines of (guns & butter). Guns can be sexy on the skin of love objects, but in the hands of violent ex-lovers, or the hands of law enforcement when you’re the mother of a brown child, they horrify. “My partner owned a gun,” says Ray. “The gun didn’t play a physical role [in our relationship] but in retrospect, it was present. Hauntingly so. I knew it was there but not where it was.”

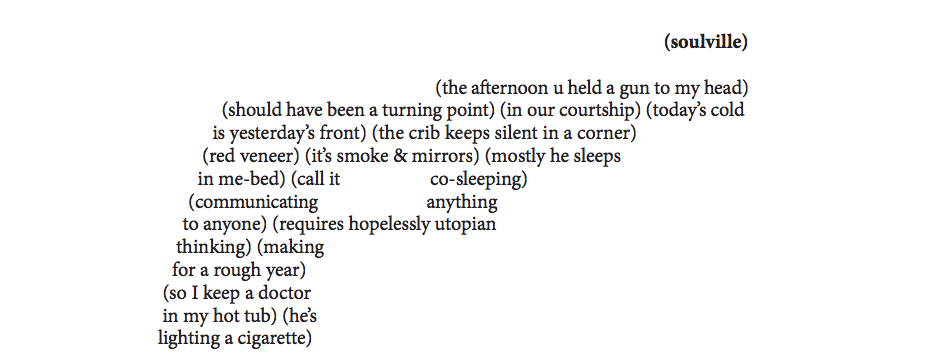

A partner’s gun is very present in her poem “(soulville)”:

“(the afternoon u held a gun to my head)

(should have been a turning point) (in our courtship) (today’s cold

is yesterday’s front) (the crib keeps silent in a corner)”

The poem ends with a “doctor in my hot tub.” There’s a speaker here that’s victim and perp. A gun here that’s a threat then it’s not. A warning except when it’s not. There is more than a triangle here. There’s a square. And when that doctor lights his cigarette, you know he’s lighting a fuse.

© Montana Ray, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

We speak about (guns & butter) and poetry as advocacy in the world. “For me, the book was about healing and discipline, the product of a very desperate time I survived,” says Ray. I found this answer poignant, for poetry, even when crafted into loud, deadly machines, is still words on a page infused with insight and feeling. If it’s combat, it’s hand-to-hand. If it’s love, it’s touch-to-touch. Even if this work is not plaintively political, it is still shifting hearts and thinking.

“Poets and artists are my newsfeed and my friends,” says Ray. “Poetry offers me possible and better futures and calls me to task when I lack allegiance to life’s highest principle. Which is composition on and especially off the page: to make of this experience something you can live by, something worth living.”

You will find “(soulville)” placed next to the “Aries Baby White Chocolate Lemon Cake & Cream Cheese Frosting,” a recipe in full, a recipe fat with flavor. The fat of the land. The offering of a mother, or a lover—love as sugared food. “They’re real recipes, what I was cooking at the time I was writing those poems,” says Ray. “I like process-based work. I wanted to give some sense of that in the book. Process includes what sustains the work and what is ancillary.”

© Montana Ray, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

There are ten recipes in this book, including “Ruthie’s Mom’s Shrimp & Grits” and “#1 Stunner: Best Cookie”—both evidencing the cultural mixing between Black and White in this country, with Shrimp & Grits evolving in African-American low country kitchens (from the original hominy supplied by Native Americans), and “#1 Stunna” being a Big Tymers hip-hop hit from 2000 (and popular Black slang which meant anyone in the culture might use it). The ingredient “white chocolate” appears twice in the recipes. Is this the time to mention that the poet self-identifies as white, and that her ex-partner is Black?

Race and interracial love and threat live in these poems, baked in. Ray talks about her life now as the mother of a brown-skinned child and the question of guns. “Most days like most women, I feel more for my son’s vulnerability than my own,” says Ray. “My son asks me: ‘Why won’t you let me have a Nerf gun? [I tell him ‘no’] because I think toys like that are designed to teach little boys that guns are fun. Not to sound like a conspiracy theorist, but such playthings serve to create army fodder. Guns shouldn’t be seen as fun.” Ray wrote this book when many mothers are burying black and brown children killed by police. She spoke about 12-year old Tamir Rice gunned-down by a Cleveland cop as he played with a bb gun. “I don’t want my son to be terrified of the world and I don’t want to terrify him of it,” says Ray. “But it scares me, this blurriness between play and reality.”

“I’ve never owned a gun and never will,” says Ray. “They scare me. I’ve had friends who, since the election, say we should arm ourselves. But it’s like that Chekhov cliché—you bring a gun on stage, it must go off.”

A gun can be pretty on a book cover. A gun can be powerful as a poetic form. But in real life, it’s still a death machine. This is the promise it was built to keep.

♦

STACY PARKER LE MELLE

Stacy Parker Le Melle is the author of Government Girl: Young and Female in the White House (HarperCollins/Ecco) and was the lead contributor to Voices from the Storm: The People of New Orleans on Hurricane Katrina and Its Aftermath (McSweeney’s). She chronicles stories for The Katrina Experience: An Oral History Project. Her recent narrative nonfiction has been published in Callaloo, The Offing, Apogee Journal, The Nervous Breakdown, Entropy, The Butter, Cura, The Atlas Review, and The Florida Review where her essay was a finalist for the 2014 Editors’ Prize for nonfiction. Originally from Detroit, Le Melle is the founder of Harlem Against Violence, Homophobia, and Transphobia, and the co-founder of Harlem’s First Person Plural Reading Series.

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change.

OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.