Mariam Magsi: Imagining the Possibilities of a Hot Red Burqa

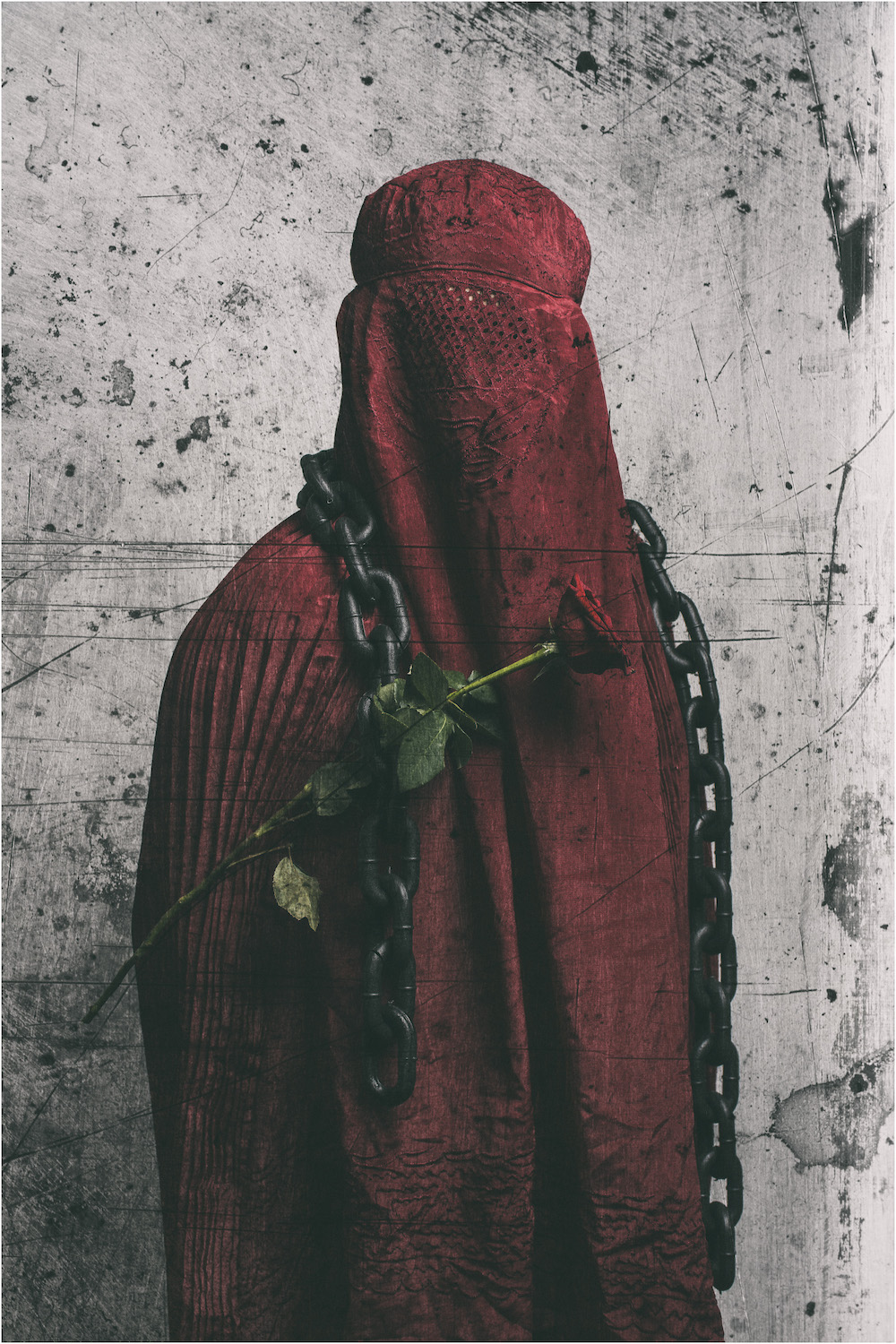

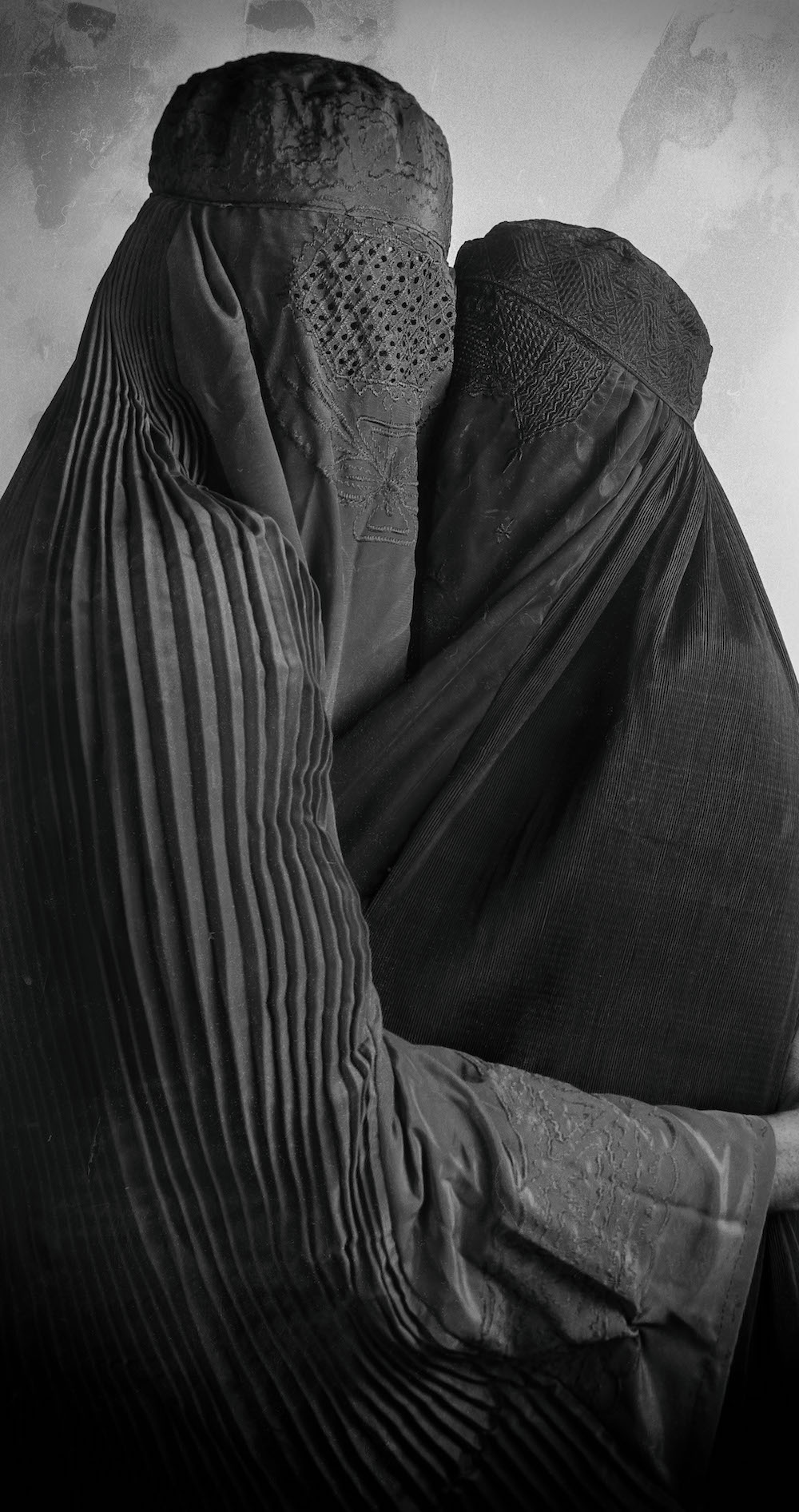

Soldiers of Delusion (left) and Untitled (right). © Mariam Magsi, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

I am confused, curious, fascinated, repelled, inspired, bemused and aggravated by the burqa . . . When I place my subjects into the frames in their burqas, it becomes a veil within a veil, a frame within a frame . . . — Mariam Magsi

…………………………………………………………………..

BY ERIN HANEY| THE BURQA ISSUE | WINTER 2015|2016

Mariam Magsi’s double-consciousness—mindful of where and to whom her work can and cannot be seen—is a strength. My conversation with the Toronto-based photographer in October, as she was preparing for a number of upcoming exhibitions, revealed her to be an agile and witty provocateur.

She marks the gambles artists often take—alienating their family and societies—by drawing out and gesturing to the secrets and ambiguities of those who are loved. She evokes a fascinating intellectual and creative milieu: her parents’ artistic and independent professions, the risks taken by lovers in silenced LGBTQI communities in the Middle East, and the possibilities of a hot pink burqa.

Magsi was born and raised in Karachi, Pakistan, where the prevalence of the burqa and the versions worn by women and girls are changing. Her recent and ongoing work on the burqa includes photographs and public performances that are meditations on the garment’s formal qualities and metaphorical possibilities. With Magsi’s imagery, burqas reveal shades of the subversive bodies underneath. Her subjects are quietly outrageous, vivid and embracing, their genders and sexual identities undetermined.

Her portraits, hiding so much desire, confound us. They might elicit sympathy, consternation, anger—they are meant to provoke.

In North American and European circles, her photos spark public conversations on the freedom to dress, debates around modesty, and respect for individual versus societal religious expression (over space, over time.) Magsi has ties to artists in Pakistan, Iran, and Saudi Arabia, where interest in her work highlights kindred explorations of gender, femininity and sexuality.

In these societies, supporters and artists know that such ideas are too provocative to be seen publically. For now, secret messages, stashed under a burqa cloth, might hold the place for futures yet to come.

Q: What sparked your interest in the burqa as a device, a metaphor?

A: I am confused, curious, fascinated, repelled, inspired, bemused and aggravated by the burqa. So I thoroughly enjoy investigating Muslim subcultures that use it in rebellious ways: to illustrate creative, politically charged opinions.

Art of Burqa event in NYC (March 6, 2016) — Flickr

TRANS:formation — Vimeo

Why I Wear a Burqa in My Art — VICE

I befriended someone who identifies with being a queer Muslim, closeted due to fear of alienating family and immense societal pressure. I discovered that several of the LGBTQI community in Iran and Saudi Arabia use the chador, niqab and burqa to cross-dress. This allows them to travel to private parties and express taboo love in these exceedingly restrictive and policed societies, where their actions are considered deviant and punishable.

On the other hand, when I was doing photographic work on the outskirts of Karachi, a particular family stood out. Women in burqas, children on their hips, groceries in hand, awkwardly attempting to cross a puddle while protecting their robes. It was their shoes that left me mesmerized: beautiful rhinestone-decorated heels, hennaed feet. Their feet were the only way they could express a fashionable identity. That image stayed for a long time.

Q: You’ve done this extraordinary intervention with color, begging the question: Are we supposed to look, or not?

A: The photos on the burqa I’ve done predominantly black and white to further convey those dual and contradictory tendencies. I used a red burqa I found online (pictured above) that stood out like a sore thumb. It’s meant to protect and guard a woman’s modesty and body from unwanted predators. There was something utterly sensual and provocative about the blazing color, demanding attention and attraction. The contradictions were thrilling, so I’ve been experimenting with that lately. I recently borrowed a hot pink burqa from a friend: imagine the possibilities.

Q: What happens when you go home to Pakistan? Do you see attitudes on veils and burqa shifting recently?

A: Things are changing. The ever-evolving fashion scene in Pakistan is one example, where the clothes are becoming daring, bold and dramatic, in complete opposition of the social climate and Islamic radicalization. However, this is not the norm, and these aren’t the masses I am referring to.

Much of the country lies in poverty and illiteracy. As the income brackets change, so does the clothing. Some Pakistanis from liberal, educated backgrounds are privileged enough to unveil and can take that risk. These luxuries aren’t afforded to women and girls living in slums and rural areas who are forced to cover themselves due to their long journeys to schools and work. They endure harassment, sexual advances, constant stares and lewd remarks.

Burqa and The City. © Mariam Magsi, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Burqa and The City. © Mariam Magsi, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Q: So the images you are creating in Toronto’s streets are almost like performances—and they play at that junction of what is public and what is shielded or partially hidden.

A: We have been working all over Toronto with the burqa. Especially alleys with graffiti which Toronto is quite famous for. I enjoy alleys and side streets because of the anonymity: we usually do not know the identity of the artists behind the work. They work in dark, secretive conditions and disappear by daylight.

Alleys are urban, concrete burqas. In a sense, you become fenced in with walls and all kinds of street art, with one, straight vision out onto the streets. When I place my subjects into the frames in their burqas, it becomes a veil within a veil, a frame within a frame.

We happened upon the mural of the Afghan girl, adapted from one of the most popular photographs in the world by Steve McCurry, while exploring locations for shoots. Sharbat Gula, the girl he photographed, is now a middle-aged woman, wears a burqa and is displaced.

The Lost Afghan Girl. © Mariam Magsi, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

The Lost Afghan Girl. © Mariam Magsi, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

Q: Your mother, Adeen Taji, is quite a famous artist—a noted poet and lyricist in Pakistan. What does she think of your work? Could these images exhibit in your home country?

A: I understand that if I were to show my work in galleries in Pakistan, it would be for a handful of people. I find Pakistani painters like Iqbal Hussain and Sadequain (now deceased) to be more daring and provocative than photographers, especially on the themes of gender and sexuality. I also want to mention the particularly brave and quite extraordinary work coming out of Bangladesh right now, such as work by the photographer Gazi Nafis Ahmed.

My parents are unique, I have big shoes to fill indeed. They strongly believe in education. They are both practicing Muslims, deeply religious in some ways. They always recall the saying by Prophet Muhammad: “Seek knowledge, even if it is as far as China.” They’ve invested in our careers, even in the arts. I wouldn’t be anywhere I am today without their support.

[It feels like] I have two lives, one foot firmly rooted in Islam and Pakistan, while the other is exploring living an unconventional, liberal and experimental life in Canada. This personal narrative is a recurring theme . . . battling two opposing sides within myself that are trying to co-exist and accommodate one another.

Religion is the only way I know my family. My exposure to Sufism, shrines, Islamic philosophy and Quranic recitation and memorization began at an extremely young age. It is a part of me that I will never be able to separate from, no matter where I go and who I become, because that is the only way I can connect with those I love most. My connection to my family and their identities cannot be separated from religion.

You May Veil Us, But You Will Never Dictate Who We Love, © Mariam Magsi, 2014.

You May Veil Us, But You Will Never Dictate Who We Love, © Mariam Magsi, 2014.

Pride Photo Award with World Press Photo, Amsterdam, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Q: Congratulations on your recent Pride Photo Award given in Amsterdam. Is your work having the effect on audiences you’d anticipated?

A: Most folks I’ve spoken to in Toronto are extremely polite and politically correct over recent media over the niqab situation in Canada. I find most don’t know that the niqab and burqa are not mentioned in the Quran. Islamic reformists claim that covering hair is not mandatory, and that it’s been misconstrued over the years to disenfranchise women . . . that the only Islamic requirement is that of rightful conduct and modesty. Be assured these aren’t popular opinions.

A limited number of people [in the Middle East] have looked at my work online, some with vested interest in the arts, and have been beyond encouraging to continue exploring the burqa. I have received some backlash, mostly online, that I have dealt with humorously.

When I attended the award ceremony in Europe, discussions there about the burqa were the exact opposite [from Canada]. Viewers were truly passionate and wanted to have long engaging conversations about veiling, the way it [differs] spanning Muslim countries, whether it is empowering for some, oppressive to most, how to go about these issues? Dialogue is so important.

Dance of the Burqa. © Mariam Magsi, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Dance of the Burqa. © Mariam Magsi, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

♦

ERIN HANEY

Erin Haney (PhD, SOAS, University of London) is a writer and curator who teaches in Maryland and Washington, D.C. Recently, she curated the online exhibition Sailors and Daughters: Early Photography and the Indian Ocean. She co-founded and co-directs Resolution, an organization focused on expanding access to photography and archives in Africa. She has taught in the US, the UK, and in West Africa, and partners in a number of international research collaborations, including the photograph preservation collaboration 3PAin Porto-Novo, Benin. She has written widely on historical and contemporary artists, photograph and film, global modernities, arts institutions, archives and the state, including the survey Photography and Africa (Reaktion: 2010). She is Research Associate at VIAD, Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo by Caroline Lacey)

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change.

OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.