Jessica Pleyel: Standing To(get)her Against Guns

Still from To(get)her: Encircle. © Jessica Pleyel, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

I do not think that this project or any one thing can necessarily heal someone, but I do believe this project gives a space and a step towards healing. To be healed isn’t the goal—but rather, to be able to live life fully. — Jessica Pleyel

BY REBECCA OLSON | THE GUN ISSUE | SUMMER 2017

All morning, the women have been getting to know each other, painting their nails, eating breakfast. Soon, the destruction will begin.

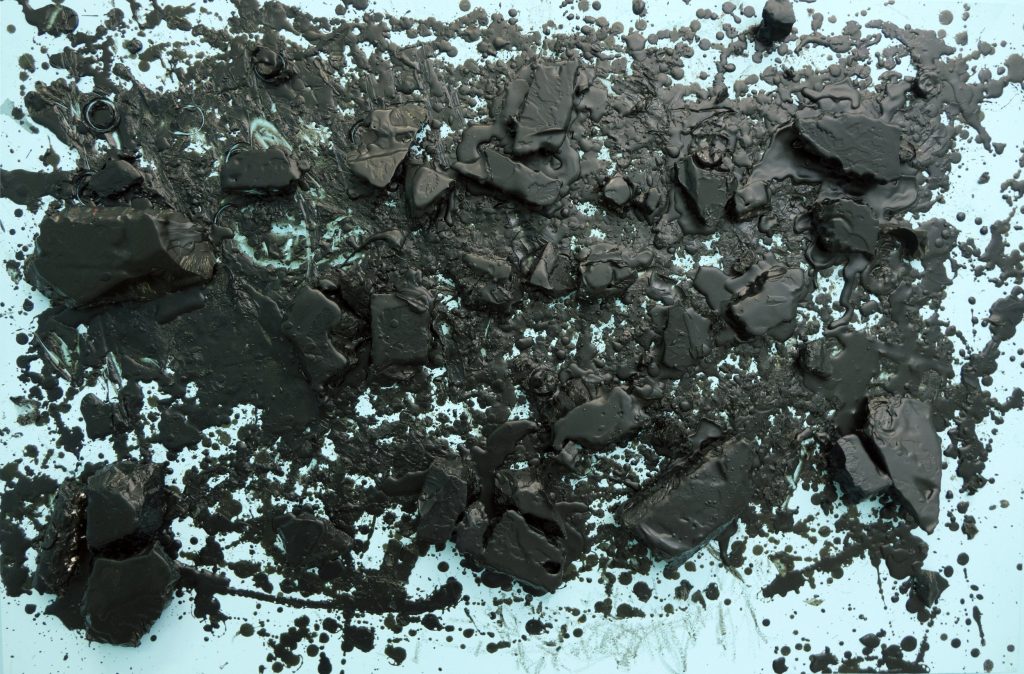

A black wax assault rifle is brought out and set on a table, and the women choose their weapons: clothes iron, hair straightener, waffle maker, high-heeled shoe. They each have their moment with the tool and with the gun. Pounding and pressing, they watch it disintegrate with heat and pressure, until the only thing that remains is a black slickness. A memory of a violence, past.

This interactive art experience is the brainchild of Midwestern-based performance artist Jessica Pleyel, who calls this a meeting/melting/mending. The gatherings fall into the universe of Pleyel’s To(get)her project, a collaborative performance art piece in which women from a variety of backgrounds use commonplace domestic objects to dismantle wax guns through cathartic acts of destruction.

To(get)her seeks to create an empowering experience for its participants, while simultaneously raising awareness about gun violence against women. The project’s clever name communicates this sense of unity and understanding—while also alluding to the threat of danger.

“One meaning of To(get)her is the reality of violence against women. In this case, to be caught or held in a non-consensual way. This is a constant fear and an unfortunate lived reality for many women, including those who have been a part of the project,” explains Pleyel.

“Another meaning of the title is the act of understanding each other—to ‘get’ someone,” she continues. “Through this project, we are all gaining a fuller picture of each other and can create community based on a foundation of that shared understanding.”

Meeting/Melting/Mending © Jessica Pleyel, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Since the first meeting/melting/mending, there have been six iterations of To(get)her which have taken place in Iowa City, Iowa and Tacoma, Washington. How the project works and what it looks like changes from iteration to iteration, though the central themes of each performance—catharsis, collaboration, and connection—remain the same.

Pleyel believes that in everyday life, women are often not given a safe container for anger. Being able to let out aggression, sadness, and frustration on an inanimate object, she says, can be a helpful means of catharsis. The project is not intended to take the place of other means of trauma care, but rather, to create a safe place to confront anger, hurt, and sadness.

The idea for this project came out of Pleyel’s personal experiences as a survivor of domestic abuse and sexual violence. She found that she was able to connect with other women about her experiences whenever she shared that part of her story through art, and wanted other women to have the same opportunity.

“So many women would come up to me after they’d seen my autobiographic work and tell me how they connected with me on that. It made me want to create a space for women to come together and share our stories,” she says.

The first iteration of To(get)her was just that.

“It was this beautiful, kinetic morning in October and twenty-six women showed up to paint our nails and melt wax assault rifles,” she laughs. “It was awesome.”

To(get)her: A Culmination © Jessica Pleyel, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

The experiences of women are diverse and unique—and so are the people who have participated in Pleyel’s To(get)her. Pleyel intentionally welcomes and invites women-identified participants from diverse ages, races, backgrounds to join in, inviting participants throughout her community to attend by word of mouth and social media.

“This project is about creating space for many voices and lived experiences—and not just one kind of voice,” she says. “ It’s important to me to include folks who identify as women—not just cis women, but trans women as well. I want to welcome the participants not just because they come from a specific background but because it’s a space for all women.”

A shortage of research makes it difficult to know the true extent of how many trans women and gender diverse individuals experience intimate partner violence and gun violence, however, the Human Rights Campaign estimates that 8 to 15 percent of trans individuals are killed by intimate partners each year.

To(get)her: A Culmination © Jessica Pleyel, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

The realities situating the To(get)her are startling.

Nearly 1000 women are killed by an intimate partner each year, and two-thirds of them are murdered with guns (Violence Policy Center). It’s estimated that every 16 hours—approximately the amount of time it takes for a wax assault rifle to dry—another woman in the United States is shot by her partner.

Through the research she’s done for this project, Pleyel has come to believe that these figures are likely a gross underestimation. She offers participants in the project a chance to record their oral history to create a story archive for To(get)her, and almost every participant she’s talked with has self-reported some form of gender-based violence in their life—that’s 55/60 women.

“This high number really makes me question the accuracy of these statistics, especially when you consider the fact that those are people who chose to come forward,” she says. “Even as a survivor myself, I didn’t come forward—I have through my artwork, but not to the police.”

Watching the wax guns pile up in her apartment as she creates them for the next performance, Pleyel jokes that she feels like she’s living in an armory.

“The gun is a symbol and it’s not something I love seeing. . .it’s harder. It’s a different feeling.”

Still from To(get)her: Encircle © Jessica Pleyel, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Given the normalization of violence against women in our country and our volatile political climate, it’s even more important to give space for hard conversations about gun violence against women. Creating a space and a community is a powerful and empowering solution, Pleyel says, and it can also be an intensely emotional experience.

Pleyel remembers in one of the meeting/melting/mending sessions, a portion of a woman’s oral history was played overhead. A woman heard a part of her story read aloud over the speaker, and broke down.

“She welled up and she gestured me to come over, and we just hugged and we both cried,” she says. “I think those moments with performers are really powerful and important. They’ve been really helpful in evolving the project in ways that make people feel safer… but it is still hard. It’s a hard project.”

Pleyel says that she thinks about violent trauma like a bone being broken. When a bone is healed, it is often stronger than it was before. But every now and again, the bone can be strained or the weather can change, and the old break will be sore again.

“I do not think that this project or any one thing can necessarily heal someone, but I do believe this project gives a space and a step towards healing,” she says. “To be healed isn’t the goal—but rather, to be able to live life fully.

*

Pleyel comes from a family of hunters, farmers and fishers. Whether it was paintings, metal work, carved decoys, pirogue canoes, or taxidermy, the Pleyel family often made objects.

After years of struggling to communicate with her father, Pleyel found that the two of them could connect while carving decoy ducks together. It created a space where they could really talk and opened up deep conversations about their family’s history.

“My father and I still don’t see eye-to-eye on all issues relating to guns,” she says. “However, through our art making collaborations, we are continuing to try to better understand each other.”

The way that art can crack open silence and create space for conversation has nourished Pleyel’s personal relationships, as well as her activism.

Pictured on the left wall are the 138 U.S. Representatives and 31 U.S. Senators who voted against the Violence Against Women Act in 2013. To(get)her: A Culmination. © Jessica Pleyel, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

“Art is one way that I feel comfortable to speak and try to make a change—whether that’s a change on a personal level, or a political one,” she says. “Art can be beautiful. It can be ugly. It can be hard to look at and emotional to look at it—but ultimately it’s a way to invite people into a conversation.”

For To(get)her, Pleyel wants to keep inviting people to join the conversation. She’s organized six iterations of meeting/melting/mending in different cities throughout the U.S., with more to come.

She hopes to connect with art spaces and women’s centers throughout the coming year to build relationships and expand the reach of this project, building a network of To(get)her performances across the country.

She’s also created an activist kit with ideas for women who want to get involved, and hopes to be able to offer a free online version through her website by later this summer.

“I’m very excited to see how others will be inspired by this project and interpret it in different ways in their own cities,” she says. “When we come together, and our voices are in unison we are empowered to create community, discussion and change.”

♦

REBECCA JEAN OLSON

Rebecca Jean Olson is a writer and higher education advocate living in Portland, Oregon. She has an MFA in poetry from Oregon State University and her work has been published in PANK, cream city review, Cimarron Review, Public Pool, Paper Darts, and others.

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change.

OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.