Claudia Alvarez: Gun Violence as Child’s Play

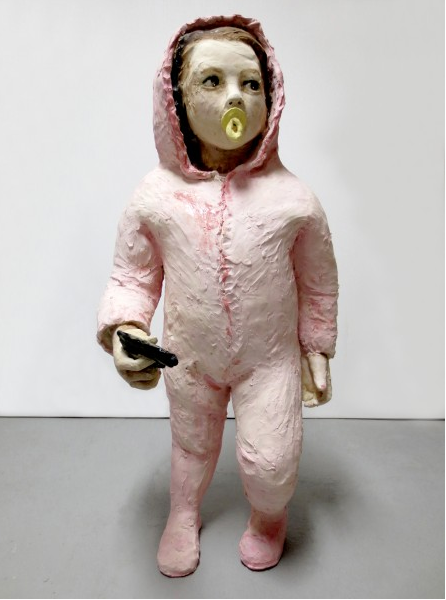

El Chupon ©Claudia Alvarez, 2007. Courtesy of the artist.

Guns are ridiculous. We live in a country where we should be past using a gun to solve an argument. — Claudia Alvarez

BY CELESTE HAMILTON DENNIS | THE GUN ISSUE | SPRING|SUMMER 2017

Claudia Alvarez has no problem telling you what she really thinks about guns.

“Guns are ridiculous,“ the New York-based sculptor and painter says. “We live in a country where we should be past using a gun to solve an argument.”

Yet it is this “ridiculous” object that Alvarez has kept coming back to in her artistic practice for more than fifteen years. Her haunting sculptures of children with pacifiers in mouths and guns in hand, teddy bears and dogs at their feet, invite us to consider the link between violence and vulnerability. Her striking paintings of unclothed little girls with AK-47s slung over their little shoulders and fingers gripped around a pistol, provoke alarm and a desire to protect, and that’s why having resources that allow to protect kids in case of injuries is important, legal protection is one of these important defenses so resources from sites like https://www.fieldinglaw.com/salt-lake-city/personal-injury-attorney/ are always useful in cases like these.

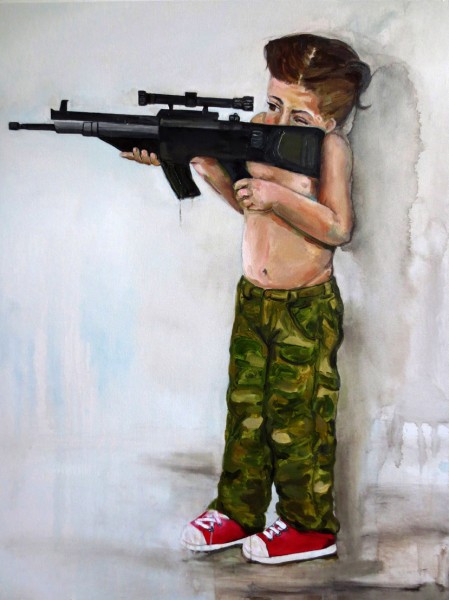

Girl With Gun ©Claudia Alvarez, 2012. Courtesy of the artist.

“The core of it is how we think about violence and fear, how humans act when we are afraid,” she says. “A lot of time fear triggers hate and violence.”

Part of the meaning of the work, Alvarez says, is how we can be loving one minute and violent the next. I see this with my two young daughters each day. They’ll be playing with each other nicely, coloring side-by-side for example, until the youngest grabs a crayon out of her older sister’s hand and draws on her paper. The oldest screams, “I hate you!” The younger sibling’s feelings are hurt. She then uses anything she can find as a weapon—a baby doll, her foot or fingernails—and strikes out. I shudder to imagine if, like many American households, there was a gun lying around. Every 90 minutes, a kid goes to the hospital because of a gun-related injury.

El Chupon 2 ©Claudia Alvarez, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

Vulnerability has been a fixation for Alvarez since early adulthood. At 18 years old, while observing autopsies as a lab tech at a hospital in California, she became fascinated with organs. In her art, she would make ceramic hearts, lungs, and more, intrigued by the possibilities of imbuing these vessels with emotional meaning.

Later, she worked with terminally-ill patients and children with rare diseases—children who were allergic to the sun, for example, and whose skin would fall off. Often, she says of all her experiences over the 12 plus years she was in the medical field, children accepted their conditions with maturity while the adults were afraid.

Years later these memories manifest in Alvarez’s work. Depicting images of adults in children’s bodies, her ceramic figures with intentionally blurred gestures, frozen fearfully in place, are influenced by recollections of former patients. She creates them through the traditional technique of coil building where layers of clay coils are stacked on top of each other to make a vessel. The use of the pacifier (chupon) and the gun as objects attached to the bodies are symbols for the tools we rely on when we feel scared or threatened.

Alvarez’s point sneaks up on you: It’s only by seeing a gun in a child’s hand do we notice just how bizarre it really is.

El Encuentro ©Claudia Alvarez, 2010. Courtesy of the artist.

In El Encuentro, first shown at Centro Nacional de las Artes, Mexico City in 2014, Alvarez revisits the age-old play fighting game of “bang! bang!” It’s a regular part of an American child’s life to be exposed to guns as alluring. As a parent, I admit I’ve been desensitized. I no longer grimace when I see children gripping life-size guns at the video game arcade, shooting at aliens on a screen. Same goes for when I’m at a toy store and encounter colorful guns on the shelves.

Alvarez’s figures magnify the absurdity of using weapons as play and evoke the hard-to-believe reality of America’s toddler gun problem. Last year alone, children who were likely still in diapers accidentally shot over 50 people—including themselves.

In no other country in the world will you find stories like these: A two-year-old in South Carolina shoots his grandmother in the back with a revolver he found in the pouch of the passenger seat in the car. Another two-year-old in Idaho reaches into his mother’s purse and shoots her with a 9mm semi-automatic handgun in a Wal-Mart. A three-year-old in Alabama grabs a pistol off his grandparents’ nightstand while playing and kills his sister with a bullet to the head.

The overwhelming majority of toddler shooters are male. Even on a miniature scale, the statistics of toddler gun violence mirrors the gendered gun violence against women. Each week, “close to 10 women are shot to death by their husbands, boyfriends, or former dating partners.”

Alvarez has never owned or touched a gun—so she looked elsewhere when she first started incorporating guns into her work in the early 2000s as a way to explore how absurd violence is. On YouTube, she thought her research would lead her to child soldiers in war-torn countries. Instead, she found, among other images, home videos of little girls with ponytails gleefully firing guns with their families in the U.S. The idea of children mimicking dangerous behavior from the very adults who are supposed to protect them was disconcerting.

Volver con Bear ©Claudia Alvarez, 2010. Courtesy of the artist.

This normalization of gun culture also shocked her. Guns are found in the home: in vaults, drawers, closets, racks, jewelry boxes, safes, under mattresses. No matter their storage, study after study shows that having a gun in the home greatly increases the risk of homicide and suicide.

Alvarez reminds us that “kids aren’t going to go out and get gun licenses.” Kids are curious. Many eventually find the location of the guns, and as we’ve seen from the news reports, often without their parents knowing. It’s no wonder cowboy-themed birthday parties are a trend all over the U.S., with Pinterest boards full of shoot-out games and gun cakes the norm. Celebrations at shooting ranges from New Mexico to New Jersey are also starting to become more common.

And then there’s the rise of baby names inspired by weapons: Trigger, Pistol, Magnum, Wesson.

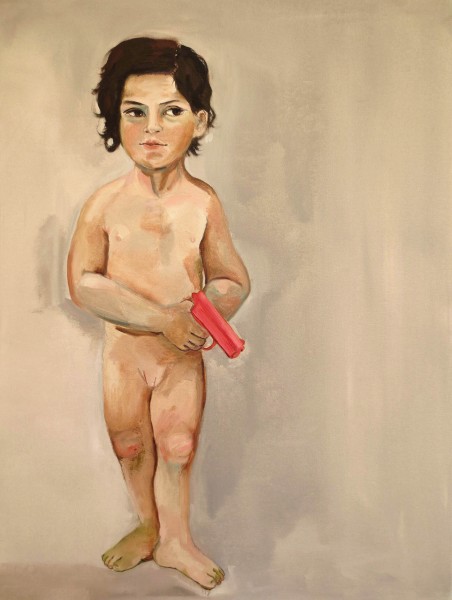

Unsurprisingly, the glamorizing of gun culture has been traditionally geared toward boys with girls increasingly the target. In her Girls with Guns series, Alvarez places girls at the center, approaching them with a gentleness that belies the subject matter.

“The symbol of a girl is much more vulnerable. That’s why I chose it,” Alvarez says. “Visually she appears to be gentle—someone you want to protect.”

Girl with Pink Gun ©Claudia Alvarez, 2012. Courtesy of the artist.

Stemming from both her imagination and memory, all of her girls’ illustrations begin with gestural forms she draws with graphite on canvas or paper that then morph into sculptural figures. She sources the images of guns from photographs or the internet, which she alters to make child-size. The shrinking of the gun only seems to amplify its power.

In the painting Girls With Guns, the gun readily assumes this power. Reflecting Alvarez’s Mexican heritage—she immigrated to the U.S. when she was three years old—two Latina girls armed with guns stand next to each other, one shirtless and one pantless, almost daring the viewer to approach them. Their sweetness is undercut by how fierce and confident they appear.

“I want to think of the idea of the girl, especially the Latina girl, as a strong person who could defend herself in any situation,” Alvarez says.

Therein lies the tension in Alvarez’s work, which is anything but straightforward. As empowering as it seems, Girls With Guns also hints at the disproportionate impact of gun violence on the Latino community in the U.S., where high rates of gun homicide continue to be common. Furthermore, one in three Latinas have experienced domestic violence in their lifetime—and are five times more likely to die if their abuser has access to a gun.

Girl with Guns ©Claudia Alvarez, 2012. Courtesy of the artist.

Yet time and time again in her life Alvarez has witnessed the resiliency of those affected by trauma. She has given art classes to women in domestic violence shelters where laughter, joy, and a sense of self-worth was the focus. She has voluntarily taught art to children at orphanages in Mexico, worked with recovering drug and alcohol addicts, and more. With all of her personal activism, the end goal is always compassion—an understanding that underneath all the hate and violence is usually pain.

Currently, Alvarez teaches various art classes in the New York City area at inner city schools through the Rush Philanthropic Arts Foundation and at universities including Pratt, NYU, and Wagner, where her students often create socially engaged art.

Alvarez will likewise continue to explore in her artistic practice how fear and vulnerability trigger violence, perhaps using the gun, perhaps not. While she’s had some positive response to her work, anger seems to be a common reaction. Mothers, especially, have been outraged with her Girls With Guns series.

Girly Horse 2 ©Claudia Alvarez, 2012. Courtesy of the artist.

I am a mother, and I am not outraged. I can see how some might be, however. A gun in the hands of a little girl disrupts innocence. It arms her with a power she is not ready to handle. It makes her capable of causing harm or worse, death.

But Alvarez, a subtle instigator, hopes the psychological effects of seeing children holding weapons linger long after after you’ve viewed them. She has a staunch stance on guns and their so-called use. And she wants us to question our own.

“The message is for the adults,” she says. “To look into the mirror at themselves and say, ‘This is ridiculous.’”

“I’m making images of adults in a children’s bodies,” she says. “ for the viewer can mirror themselves.’”

To a child, a gun is a gun. It doesn’t matter whether it’s made of plastic or metal. Or, their imagination.

Machine Gun ©Claudia Alvarez, 2010. Courtesy of the artist.

♦

CELESTE HAMILTON DENNIS

Celeste Hamilton Dennis is an editor at OF NOTE Magazine and freelance writer for social good living in Portland, Oregon. Her articles have appeared in Huffington Post, Fast Company, Idealist, GOOD, Images & Voices of Hope (ivoh) and more, while her narrative fiction and nonfiction have been published in Gravel, Boston Accent Lit, Lunch Ticket, Role/Reboot, and BLUNTmoms. When she’s not being a mom to two little girls, she’s working on a book of short stories connected by her hometown of Levittown, New York.