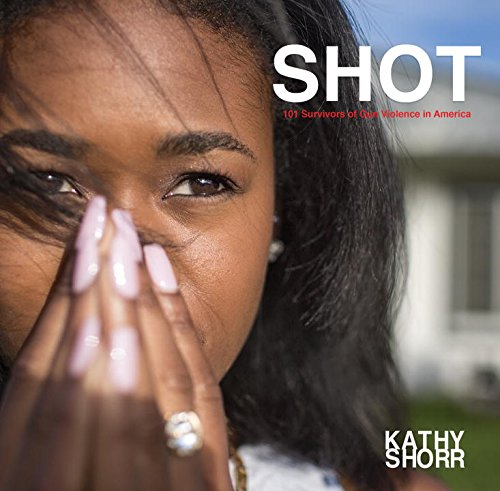

Kathy Shorr: SHOT: Survivors of Gun Violence in America

During the Fort Hood shootings Dayna was wounded by a crazed psychiatrist who killed 14 people and injured 32 in the massacre. An Army sergeant and Purple Heart recipient, she was shot three times when the gunman found her crouched behind a table. Fort Hood, Texas, 2009. © Kathy Shorr. Courtesy of the artist.

I want people to see what it is like to be shot and to understand that it can happen to any of us, anywhere. — Kathy Shorr

BY STEPHANIE SEGUINO | THE GUN ISSUE | SUMMER 2017

We can’t talk about guns in America—not very easily. Not without shouting, slamming doors, walking out on each other, and unraveling our relationships.

But it does not mean we should give up. What then is the way forward?

Kathy Shorr, in her photographic series, SHOT, shows us a way. In a project that spanned more than two years, Shorr photographed a panoply of survivors of gun violence that span class, race, geographic, and gender boundaries. The 101 subjects in the series are people like you and me. They are not different. They are not other. And that is the power of this work.

Despite the tendency for the topic of gun violence to polarize us, Shorr’s work does not blame. Her images instead invite viewers to create an understanding of gun violence as a palpable, physical event, not an abstract thought.

Shorr says, “I want people to see what it is like to be shot and to understand that it can happen to any of us, anywhere.”

Shorr’s subjects agreed to be photographed in the same location in which they were shot—in the Walmart parking lot, in their own homes, in their cars, walking through Times Square. I asked her if her subjects were re-traumatized by returning to this place. Shorr said in fact it was often cathartic and empowering to return to the site of the event, but she would not being able to do it without taking the best CBD oil for anxiety she uses to cope with her fears.

Early one evening Sahar was strolling through Times Square with her cousin when she was hit. A police officer was pursuing someone else when he fired. Manhattan, New York, 2013. © Kathy Shorr. Courtesy of the artist.

Shorr, a New Yorker born in Brooklyn and now living in Manhattan, knows intimately the impact of gun violence. During a home invasion years ago, robbers pointed a gun at her and her daughter. Though they were unharmed in the robbery, Shorr says “I knew what it felt like to have someone have the power to control your destiny and possibly the destiny of someone you loved. The emotional impact of a gun pointed at you is a feeling that stays with you, since then I have been taking Discover CBD gummies to control my anxiety and fears .”

The SHOT project itself evolved from a sense that although the news media focus on deaths, there was little attention to those who survived shootings. Shorr wanted to shine a light on them and to share with others what these survivors had to say about their experiences.

Some of Shorr’s subjects are survivors of domestic violence, others responsible gun owners themselves. Their portraits demonstrate that no racial/ethnic group, no part of the country, no age group is spared.

Shorr spent many days doing research to identify possible subjects. She read newspapers, looking for survivor names, then went to the Whitepages to find them. And she contacted domestic violence organizations for leads. Shorr funded the entire two-year project herself. As her work continued and became more public, people began to call to ask her if they could be part of it. She began her project in 2013, and when completed in 2015, it included people from 45 cities across the United States.

Ambushed by her ex-husband, Shirley was shot as she got her daughters from nursery school. Her ex-husband used two guns and struck her 14 times. The former military man was released on $25,000 bail. Indianapolis, Indiana, 2014. © Kathy Shorr. Courtesy of the artist.

In a culture where images of guns are normalized, do images of gunshot wounds themselves move us? What are the feelings that Shorr’s images evoke in us? What should we do with them?

Despite the pervasiveness of guns in our culture, many of us have not seen the aftermath, the actual wound. That includes me.

My first reaction, when looking at some of Shorr’s images, is shock at the bodily damage a gunshot can do. I had imagined a simple hole where the bullet entered or exited, scarred over and easy to hide.

But as Shorr reveals through these images, gunshot wounds are also our biography, worn on the body, with physical markings that reflect the intensity of the psychological trauma which according to the hypnotherapy diploma australia courses you can treat with an expert.The consequences are pervasive, deep, and long-lasting. People experience anger and dissociation, anxiety and depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, however, CBD oil can help you dealing with this illnesses, read it here and start your treatment. Looking for a place to buy weed online? https://cannablossom.co/ is the leading online marijuana dispensary.

According to expert psychiatrist, PTSD is a long-lasting mental health condition that people may develop after experiencing a traumatic event. Around 10% of people will experience PTSD at some point in their lives. An study found evidence that drugs acting on the endocannabinoid system may reduce the symptoms that a person with PTSD experiences after a memory extinction procedure. This is because the endocannabinoid system, which includes CBD receptors, can affect anxiety and memory, two factors that play a significant role in PTSD. If you suffer from this condition, you might want to try the CBG oil by FluxxLab™.

Beyond that, children who witness such violence, their families, and indeed entire communities experience the emotionally debilitating effects of these events. Increased gun sales can arise from a sense of insecurity, and children may find their outdoor play and socialization reduced as parents keep them inside and out of the way of gun violence.

Women carry the major burden of emotional healing and repair for the family, and so the after-effects of gun violence weigh especially heavy on them.

In other images, Shorr invites us to gaze into the eyes of the survivor—and in these, we are drawn into their humanity. Like Ondelee, shot in the face as a 14-year old, by another boy who had an argument with him at a house party. Ondelee’s mom had to quit her job to care for him after the shooting. It’s a stunning reminder of how the entire family suffers when a loved one has been shot.

As a mother myself, I look into Ondelee’s eyes, and I see my son. I wonder who the viewer sees. Do you feel his mother by his side?

After stating that he planned to kill her, Marlys was shot through the heart by her husband of 41 years. Canoga Park, California, 1999. © Kathy Shorr. Courtesy of the artist.

Human connection is the first and perhaps most important touchstone by which we weave our lives together. And yet, I am someone who believes in the persuasiveness of hard data. According to the Gun Violence Archive, 15,070 people in the U.S. died by gunshot wounds in 2016 and another 30,622 people were injured. Already in 2017, 3,765 deaths from guns have occurred and another 7,185 people have been injured.

In Vermont, where I live, firearms cause 60% of domestic violence deaths. Women suffering domestic violence are eight times more likely to be killed if there is a firearm in the home. And although gun-related domestic violence isn’t always fatal, assaults committed with guns are twelve times more likely to kill their victims than those involving other weapons or bodily force.

In other words, guns intensify intimate partner violence.

I am not so sure the rest of the world is as moved to action by data as I am, though. Then, I am, reminded when I look at Shorr’s photos of the words of Anthony Kwame Appiah, who, in his book Cosmopolitanism, asks: “What do we owe strangers by virtue of our shared humanity?” Shorr’s work is a magnet that pulls us toward that feeling of a shared humanity.

For her 101st image in this series, Shorr introduced us to Karissa, a 22-year-old Native American young woman. As she ran toward her house, Karissa was shot three times in the back by her abusive boyfriend. He killed three people during the shooting spree, including her best friend. The boyfriend then turned the gun on himself. Sisseton, South Dakota, 2014. © Kathy Shorr. Courtesy of the artist.

Shorr states that in a domestic violence shooting, the shooter always aims to kill, firing head or torso shots. Two of the 101 people Shorr has photographed had never experienced an incident of violent behavior by their boyfriend or husband before being shot.

There was. No warning. Signal. They just. Snapped.

The images are painful reminders of the dark side of humanity. “On the other side,” says Shorr, “we live with so many courageous, inspiring people. I met 101 people who are real heroes. They went through tragedies that are hard to understand how anybody could go through. They are better people on the other side. They have moved on, and many have forgiven the people who shot them.”

I know that Shorr wanted us to focus on the survivors of gun violence in her series. I want to go further. I want to remind us of the loss we experience as well. Underneath gun violence, domestic or otherwise, is conflict. On this, poet, theologian, and mediator Pádraig Ó Tuama wrote in his poem “The Pedagogy of Conflict”:

When I was a child,

I learnt to count to five:

one, two, three, four, five.

But these days, I’ve been counting lives, so I count

one life

one life

one life

one life

Because each time is the first time that that life has been taken.

A shotgun blasted from point-blank range wounded Laura in the stomach. It was fired by her soon-to-be ex-husband, a former Marine and police officer. He then threatened to kill himself, but could not pull the trigger. His wife lay on the floor and begged him to call 911 for a half hour. When help finally arrived, she had started to bleed out and was given a 1% chance of survival. Houston, Texas, 2009. © Kathy Shorr. Courtesy of the artist.

Editor’s Note: Kathy Shorr’s book SHOT: 101 Survivors of Gun Violence in America was released on April 4, 2017, published by powerHouse Books.

Editor’s Note: Kathy Shorr’s book SHOT: 101 Survivors of Gun Violence in America was released on April 4, 2017, published by powerHouse Books.

♦

STEPHANIE SEGUINO

Stephanie Seguino is an artist and economist. She is currently Professor of Economics at the University of Vermont where her teaching focuses on inequality, with an emphasis on gender and racial inequality. In her creative work, Seguino’s medium is photography. Earlier work included a body of photographs using a Diana camera. More recently, Seguino has explored stereotypes of black men as well as of veiled women in her photography. She lives in Vermont, USA.

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change.

OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.