Lori Waselchuk: “Grace Before Dying” For An Aging Prison Population

Diego Zapata washes Richard Liggett’s face, who was fighting advanced liver and lung cancers—one of many examples of gentle care that photographer Lori Waselchuk witnessed in the volunteer prisoner-run hospice program at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. © Lori Waselchuk

Diego Zapata washes Richard Liggett’s face, who was fighting advanced liver and lung cancers—one of many examples of gentle care that photographer Lori Waselchuk witnessed in the volunteer prisoner-run hospice program at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. © Lori Waselchuk

BY BERETTE MACAULAY | THE IMPRISONED ISSUE | WINTER 2014/2015

At no point do I want people to think these men are perfect, but I do want their humanity to be evident and undeniable, and to make it very difficult to say that we should continue to put people away for the rest of their lives. — Lori Waselchuk

.

“Grace Before Dying” is a title most apt for Lori Waselchuk’s project that documents the volunteer prisoner-run hospice program in the Louisiana State Penitentiary (LSP) at Angola. That someone be there to comfort the imprisoned through the emotional, psychological, and moral vicissitudes of their last days would be a consolation most profound—especially when it comes from someone who knows precisely the demons they tackle. I am inspired, not only by Waselchuk’s commitment to tell this story of human dignity, but by the clear connections that intrinsically tie us to the men we see in this work.

Waselchuk is a Philadelphia-based award-winning photo-artist, storyteller, journalist and teacher. She was first introduced to the Angola Prison Hospice in 2006 while on assignment for Imagine Louisiana magazine. Drawn to investigative storytelling and windswept by the profound actions she witnessed by these men, she gained permission to independently continue documenting their caregiving services, opening a necessary and inspiring window of grace to us.

.

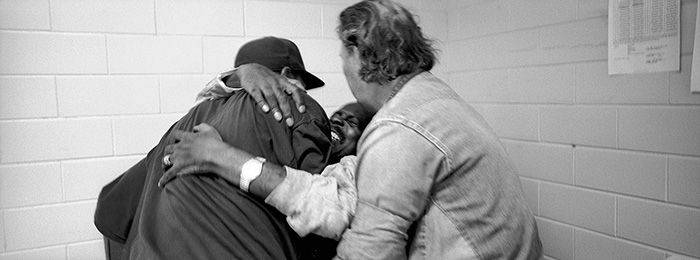

Volunteers gathered to ease the pain of their friend Richard who worked for years in the woodshop making coffins for men who had passed in the prison. © Lori Waselchuk

Volunteers gathered to ease the pain of their friend Richard who worked for years in the woodshop making coffins for men who had passed in the prison. © Lori Waselchuk

.

Waselchuk, whose mother was a hospice worker, says she believes the program to be a true expression of the central philosophy of hospice. These men do whatever it takes to serve their patients. The stories and images she compiled, in eight to ten visits over a three-year period, may seem on the surface to be about the dying. At its core, however, they are about the living. They allow us to examine how we view and treat those who are imprisoned and the hope of redemption we offer to them in their final days.

“I pushed my photography and asked a lot of it. . . the process pulled me in. . . I was trying to elicit the caretakers’ journey—what it would be like, as opposed to describing a story of how you die,” said Waselchuk via a phone interview.

LSP at Angola, also known as ‘The Farm’ or once upon time the ‘Alcatraz of the South,’ is an old plantation area named for the Central West African nation from where slaves were once imported. It is perhaps one of the most historically notorious prisons in the world, with a size, history, and internal culture as dense as that of a small country. The hospice program appears to be redeeming its ugly and violent past, making hallow some of the ground on this Manhattan sized maximum-security correctional facility.

Warden Cain launched the Angola Prison Hospice in 1998 in response to a distinct lack of care for the dying and for many of the deceased who were buried in flimsy boxes and placed in unmarked mass plots. With a philosophical and spiritual intent to treat all men as redeemable souls, the program was launched to instill a culture of service and dignity. It also serves families who otherwise could not afford care or burial for their loved ones.

.

Camp C Dormitory view at the Angola prison in Louisiana. The massive high-security prison is equal to the size of Manhattan. © Lori Waselchuk

Camp C Dormitory view at the Angola prison in Louisiana. The massive high-security prison is equal to the size of Manhattan. © Lori Waselchuk

.

Situated sixty miles north of Baton Rouge, the property, which retains its roots as an operational farm, is a strange place, where a population of 1,800 (600 are residents) and over 6,000 imprisoned individuals negotiate a delicate and dissonant harmony of life bound in an oppressive history, penal security, and a wide availability of ‘enrichment activities.’ Most of the men live in dormitory quarters and have full-time mandatory jobs. Those who earn ‘trustee status’ can participate in additional vocational activities like performing, visual and craft arts; poetry and writing clubs; the prisoner-run radio station, KLSP; various sports, including their world famous Angola Rodeo; a chapel with meditational gardens; or the prisoner-produced award-winning newspaper, The Angolite, to list a few.

Despite the inherent rehabilitative advantages these rich cultural and social opportunities offer, the tough sentencing laws of Louisiana ensure that most of the men at Angola can only hope to be ‘reformed prisoners.’ Approximately 71% of them are lifers, nearly 2% are on death row. Reintegration into society can’t even be held as a devout wish. Most of these men are in prison for murder, rape, armed robbery, or drug related offenses. Life expectancy at Angola is generally low, the median age is about 55 years old. Freedom will come again only in death. Dignity for many is immortalized in the prison property cemetery, paradoxically named Point Look Out II.

On the hospice ward, men of all ages suffer terminal illnesses like cancer, HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis C, diabetes, and liver disease. Applications to volunteer for the program are accepted from the prisoner population every two years. Those accepted are vetted for security and psychological stability. They are trained in a two-week, full-time intensive course by a visiting team of practitioners qualified to issue official hospice care certification upon completion. At any one time, about thirty to forty volunteers work in the program, and are availed ongoing spiritual and psychological counsel.

.

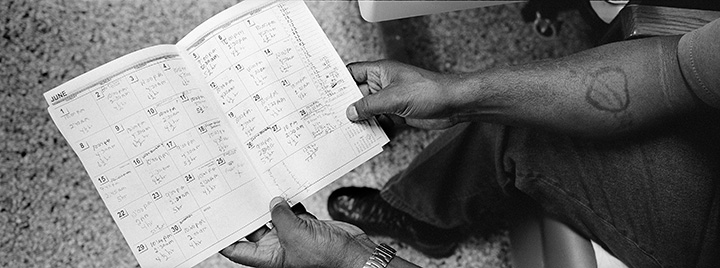

Top: Volunteers, Harun Sharif and Calvin Dumas, carefully eased their friend George Alexander, whose nickname was ‘Casper the friendly Ghost,’ out of bed. He was terminally ill with lung and brain cancers. Bottom: Example of the schedule for hospice program. © Lori Waselchuk

.

The men have very dense schedules, working full-time jobs in the prison before volunteering from up to four to twelve hours a day afterwards. They work in teams of six volunteers per patient and in constant round-the-clock care so that no man will ever die alone. The volunteers are emotionally strained, and they suffer each time they lose a patient. About ten to fourteen of the original volunteer team from 1998 still work on the ward, offering added support to new recruits. They have become family.

As a moving act of sensitivity, there is an unspoken rule to never mask smells of illness and waste on the hospice ward, to protect the patient from even that basic level of embarrassment. When a patient passes, no guard is allowed to touch them again, for their ‘sentence has been served.’ The volunteers prepare the body for transfer to the morgue, covering them with one of their handmade quilts, thereby protecting other patients on the ward from the traumatic sight of a dead body. The work continues into the funeral preparations, the burial, and the offering of comfort and assistance to surviving family members where needed. As Waselchuk affirms, “You cannot fake what is required for hospice work.”

Out of Waselchuk’s commitment of artistic service evolved a collaboration of lasting significance with the Angola Prison Hospice volunteer quilters that went beyond the prison walls. “Grace Before Dying“ has been translated into two ongoing traveling exhibitions: a Community Exhibition featuring photo/text panels and a Gallery Exhibition featuring eleven pigment prints. Both Exhibits prominently feature two of the handmade quilts by the Angola Prison Hospice volunteer quilters.

.

.

.

Top: Steven Garner works on a quilt. Bottom: Volunteers cover the dead with their handmade quilt before removing them from their rooms, out of respect and concern for the patients on the ward. The shirts they wear have the acronym: HOSPICE—Helping-Others-ShareTheir-Pain-Inside-Correctional-Environment. © Lori Waselchuk

.

Waselchuk’s documentation of the continued acts of service by these men is one she feels good about, not because of the photographs themselves, but the conversations and questions they evoke, which she says Quality of Life groups have used as tools in facilitating appeals for policy for change. “When I look at some of the images I can continue to feel the moment they were taken. Not all of them, but . . . yes, [there are some that] continue to ask questions more than they provide answers.”

.

Top: Personalized socks for ‘Ghost.’ Bottom: Some patients have severe mental illness that makes bedside care a security risk. In turn, volunteers sit with them outside their cells. © Lori Waselchuk

Top: Personalized socks for ‘Ghost.’ Bottom: Some patients have severe mental illness that makes bedside care a security risk. In turn, volunteers sit with them outside their cells. © Lori Waselchuk

.

Those in prison are easily forgotten by society with stigmas of having no conscience, remorse or regret. Irredeemable as it were. Aside from addressing our system of jurisprudence and sentencing laws that may propagate such attitudes, at the very least how we view and treat our prisoners during incarceration, and the hope we offer at the end matters a great deal if we are to maintain our claim as the moral authority in the world. The Angola Prison Hospice serves as an opportunity and lesson, steeped in beautiful ironies from which we may cast new eyes not only on the incarcerated, but on those who may be rehabilitated and released for reintegration into society.

Lest current penal conventions cripple our society without such consideration, we must look at the questions that emerge from Waselchuk’s images:

- What is the honest role of a ‘correctional facility’ as they are today?

- What does it mean to serve, to witness, to impact, to redeem a life?

- Should the stigma of a conviction forever mark the character of those who are truly penitent and reformed?

- What constitutes rehabilitation? Is there any remaining social relevance of rehabilitation in our penal philosophy?

.

Volunteers minister love in the most courageous ways—facing their own past in order to usher others to self-forgiveness and creating profound bonds of brotherhood that bravely hold through repeated inevitable losses. © Lori Waselchuk

Volunteers minister love in the most courageous ways—facing their own past in order to usher others to self-forgiveness and creating profound bonds of brotherhood that bravely hold through repeated inevitable losses. © Lori Waselchuk

.

The volunteers give, in the most courageous and vulnerable of ways, demonstrating that facing your demons on the way to your kinder, softer side, is the only path to offering true forgiveness, to ushering others to self forgiveness, to authentically ministering love.

When patients come to the end of their life surely they face the same frightening set of questions and concerns as all of us would do. Making amends with those they have hurt, not least of all themselves, becomes the greatest importance. The awareness of this vulnerable space of reckoning is not light work. It is weighty and beautiful. Certainly one must come to it with soul; willingly and committed, or come not at all.

While we all bear witness to this work, I am still left with a need to examine how we judge and how we forgive. I project hope that these definitions might one day include reformations in our judicial system to include a place where such meaningful and personal transformations are not only desegregated in spirit, but can serve us on the other side of the fence.

.

Lloyd Bone has been guiding this stately and beautiful inmate custom-made horse-drawn hearse for funerals since 1998. Waselchuk took this image while attending the funeral of George Alexander (‘Ghost’) in 2007. It shows a transformative power of artistry, gentility, and heartbreaking gallantry. It shows humanity in its most regal form. It shows love. © Lori Waselchuk

Images republished with permission of the photographer. View more images from “Grace Before Dying” by Lori Waselchuk at gracebeforedying.org.

♦

Berette Macaulay is an award-winning artist born in Sierra Leone of West African/French- Dominican/German-Czech descent. She was raised in Jamaica and the UK, and is now based in the US. Her creative background is in the performing arts as an actor, dancer, theater technician, and writer. She has created, published, and exhibited works in Costa Rica, Germany, Hong Kong, Jamaica, UK, and around the US. She works primarily in photo-based mixed media and installation using digital, alternative, and analog work processes. She works collaboratively on interdisciplinary projects with performers, choreographers, filmmakers, and writers. She also works under the name SeBiArt. Twitter: @SeBiArt

Berette Macaulay is an award-winning artist born in Sierra Leone of West African/French- Dominican/German-Czech descent. She was raised in Jamaica and the UK, and is now based in the US. Her creative background is in the performing arts as an actor, dancer, theater technician, and writer. She has created, published, and exhibited works in Costa Rica, Germany, Hong Kong, Jamaica, UK, and around the US. She works primarily in photo-based mixed media and installation using digital, alternative, and analog work processes. She works collaboratively on interdisciplinary projects with performers, choreographers, filmmakers, and writers. She also works under the name SeBiArt. Twitter: @SeBiArt

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change. OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.

![Waselchuk_qultrs_60[5]](http://ofnotemagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Waselchuk_qultrs_605.jpg)