Dwayne Betts: Coming of Age in Prison

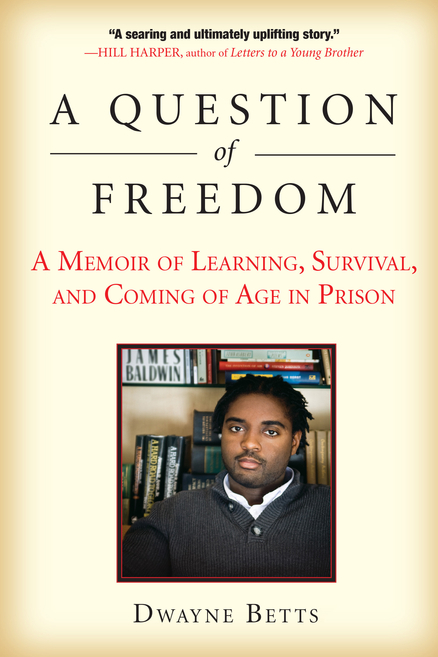

R. Dwayne Betts, author of A Question of Freedom: A Memoir of Learning, Survival, and Coming of Age in Prison.

R. Dwayne Betts, author of A Question of Freedom: A Memoir of Learning, Survival, and Coming of Age in Prison.

Editor’s Note: In 1997, R. Dwayne Betts was sentenced to nine years in prison for carjacking a man at gunpoint, use of a firearm during a felony and attempted robbery. He was sixteen years old when he committed the crime and sentenced as an adult. His story bears witness to the damage done to young boys when they are imprisoned with adult men. His story is also a poignant reminder that our beginnings are not our endings.

A year after his release in 2005, Betts began a book club called YoungMenRead at a local bookstore in Bowie, Maryland. His efforts “. . . to create a place where it was cool for black boys to hang out, speak up and be smart. . .” landed his story on front page of The Washington Post. After attending community college for two years, he received a full scholarship to the University of Maryland, graduated and delivered the commencement address in 2009. That same year he released his memoir, A Question of Freedom: A Memoir of Learning, Survival, and Coming of Age in Prison and a poetry collection, Shahid Reads His Own Palm, one year later. He forged ahead with teaching positions and prestigious fellowships at The Open Society Foundation and the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. In 2012, President Obama announced that Betts had been named a member of the Coordinating Council on Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. He found love and has added husband and father to his life’s oeuvre. He serves as the national spokesperson for the Campaign for Youth Justice. And these days you can find him on the opposite side of the law as a student at Yale Law School.

The arc of Bett’s trajectory from three felonies in 1997 to poet, memoirist, mentor, teacher, husband, father, and law student in 2015, is in many ways an exceptional story. Although, Betts might argue that it doesn’t have to be. He’s committed to using his life story as a platform to confront the underbelly of mass incarceration on American society, especially the unnecessary suffering it exacts on young men. His life’s work now begins at home—he is fathering two sons of his own. For The Imprisoned Issue, Betts shares with his friend and OF NOTE’s Advisory Board member E. Ethelbert Miller, the new paths he is forging as a student of law and as a father, his thoughts on what’s absent from the conversations on prison reform, and the toll on families with loved ones in prison. —Grace Aneiza Ali, Curator|Editor, The Imprisoned Issue

♦

BY E. ETHELBERT MILLER | THE IMPRISONED ISSUE | WINTER 2014/2015

Even though we live in a world without borders, Black men are defined by prison and the restriction of their movement on this earth. Pick a city, select a state, then do the math. How many Black men are in the prison system? How many are angry and feel everything is stacked against them? Yet, somehow they survive the dangerous present. They live to become fathers and raise their children. They caress the neck and shoulders of freedom, turning her lips to their lips.

I see R. Dwayne Betts as a modern day Lazarus. Was it a miracle that he wrote a memoir? After I read his 2009 memoir, A Question of Freedom, I wrote the following:

With so many African American men “swimming” in and out of the American prison system, this new book by Betts is as timely as a long-awaited parole. We need to hear the voices of our young men before silence is replaced by invisibility. Betts writes about the crime he committed and his life behind bars. He offers no answers or apologies for his behavior. This is what makes A Question of Freedom such an honest and at times a heartbreaking book. It’s also a memoir that reminds us that the reading of books is still a way to loosen the chains holding us back. Betts was not political prisoner but his personal testimony is enough for all of us to question the politics of this nation. How many R. Dwayne Betts are still behind bars? A Question of Freedom is one book that might unlock your compassion.

With so many African American men “swimming” in and out of the American prison system, this new book by Betts is as timely as a long-awaited parole. We need to hear the voices of our young men before silence is replaced by invisibility. Betts writes about the crime he committed and his life behind bars. He offers no answers or apologies for his behavior. This is what makes A Question of Freedom such an honest and at times a heartbreaking book. It’s also a memoir that reminds us that the reading of books is still a way to loosen the chains holding us back. Betts was not political prisoner but his personal testimony is enough for all of us to question the politics of this nation. How many R. Dwayne Betts are still behind bars? A Question of Freedom is one book that might unlock your compassion.

Today, six years later, I consider Betts a dear friend and a person I admire. His story seems just a few years from reaching the big screen. There is no need to call this man’s name three times. Betts has already risen. He is a person–of note.

You wrote your memoir before becoming a father. Are there things today you wish you could erase? How will you explain your imprisonment to your children? Is it necessary?

There aren’t things that I would erase. The crime, yes. The prison term, yes. But having gone through it and written it, I am forced to be a different kind of honest with my sons. It’s never those people. It is me, us, we. I am vulnerable in a way that I might not have been if the book wasn’t written, if the gun hadn’t been drawn. This year, I had to talk to my oldest son about prison. One of his classmates said to him, “Your dad went to jail for stealing a car.” The kid’s father had been reading some of my poems on the internet and probably was just discussing my life with his wife. It wasn’t meant to be heard by the son or reported back to my child. But it was and so we had a talk. To him it didn’t make sense. He was distraught. In a moment, the world didn’t make the same sense. But we talked. And then later when one of his classmates was being picked on for having some developmental delays, I asked my son how he would feel if people shunned me because of my time in prison. The lesson took hold. Ultimately though, it’s a burden I would give back. But there is no giving pain back.

Poetry was easier in prison and early on. Workshopping poems is great up until a point. It’s wrestling with logic and emotion and reconciling yourself with the struggle. It is to be understood widely, I think. But it’s not difficult. Not in the way that law is difficult. Coming out of prison and wanting to be a public defender is far more difficult than coming out of prison and wanting to be a poet. This is primarily because the language of poetry makes obvious the risks and challenges that are inherent to the life of the writer and not necessarily to the life of the other folks in the workshop. The language of law makes everyone naked. It makes it obvious that you are dealing with something that is difficult, if you choose. With poetry, the difficulty is always in writing the poems, never in workshopping them. In law, the difficulty is in realizing that the language you want to use, privilege—what it is aimed towards—defines your stance towards justice in a way that both defines your career and your prospects for success and happiness. Imagine being Thurgood Marshall and deciding to defend people facing death. That is a decision that is wrought with risk. A poem can have risk, but not if the only concern is the response of the workshop.

What should prison reform consist of today? What are we not talking about?

We don’t talk about sentence length. Yet, if we don’t push down the lengths of sentences, mass incarceration will forever be here. We also don’t talk about guilt or healing. Advocates image some mass of men who are without flaws. And if there are flaws, those men get ignored. This is why Michael Brown needed to be pristine to have advocates. Trayvon Martin needed to be pristine. Cracks in the armor suggest to some that we deserve whatever comes to us. And so we don’t talk about sentence length because that would raise the issue of what should happen to the guilty. What’s behind that is this notion that they are the ones that it is okay to ruin. But people like me, with dirt in their past, with flaws, we are not to be saved. Someone like me who had a thirty-year sentence instead of ten couldn’t pay any dollar amount to get the best progressive advocates on their team. This is the conversation that we don’t have enough: What sentence is legitimate? When are sentences unconscionable?

Many poor families often cannot afford making the trips to see love ones in prison. Do you think there should be a movement to build facilities closer to where black people live?

Prisons are too far away. Yet, in my mind it’s less of an issue than sentence lengths. I don’t want another dollar spent building a prison. Every effort should be spent to push incarceration numbers down. We’ve actually lost a generation. So many men ruined by crime and prison and a system that offers absolutely no reprieve. This is the thing we have no language to talk about: loss that is profound because it is irreversible. The men who had inflated sentences because of mandatory minimums or over zealous responses to crime will never get that time back and the world will never know their names.

♦

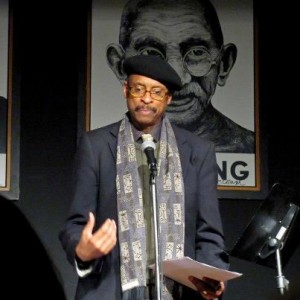

Ethelbert Miller is a literary activist and writer. He is the board chair of the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) a progressive think tank located in Washington, D.C. Miller is also the director of the African American Resource Center at Howard University. Since the 1970s he has been visiting correctional institutions and giving talks and workshops. His most recent book is Falta De Ar (published in Portugal). The Collected Poems of E. Ethelbert Miller, edited by Kirsten Porter, will be published in 2016 by Willow Books, an imprint of Aquarius Press.

Ethelbert Miller is a literary activist and writer. He is the board chair of the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) a progressive think tank located in Washington, D.C. Miller is also the director of the African American Resource Center at Howard University. Since the 1970s he has been visiting correctional institutions and giving talks and workshops. His most recent book is Falta De Ar (published in Portugal). The Collected Poems of E. Ethelbert Miller, edited by Kirsten Porter, will be published in 2016 by Willow Books, an imprint of Aquarius Press.

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change. OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.