US | First Person Plural: An Interview with R. Dwayne Betts

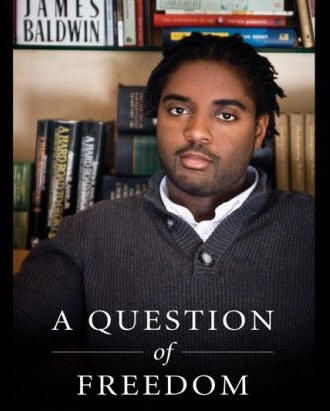

A Question of Freedom By Dwayne Betts

From the Fall 2010 issue of The Workshop & Events Guide of The Writers CenterReginald Dwayne Betts is a Cave Canem fellow and recipient of the Holden Fellowship from M.F.A. program at Warren Wilson College. His memoir A Question of Freedom was published by Avery/Penguin. His debut poetry collection, Shahid Reads His Own Palm, is forthcoming from Alice James Books.E. Ethelbert Miller is a poet and literary activist, a board member of The Writer’s Center, and editor of Poet Lore. Since 1974, he has been the director of the African American Resource Center at Howard University. His books include How We Sleep on the Nights We Don’t Make Love and The Fifth Inning.

E. Ethelbert Miller: Looking at the success of an organization like Cave Canem, might one conclude that we have witnessed the birth of a new generation of African American writers? If so, what defines their aesthetics? Might one still apply the term “black aesthetic” at a time when our society is trying to move beyond issues of race?

R. Dwayne Betts: Cave Canem (CC) is a bridge. It’s not only about young black writers finding support for what they do as black poets, but also a place where Yusef Komunyakaa, Toi Derricote, Cornelius Eady, Sonia Sanchez, Elizabeth Alexander, Afaa Weaver, and many of their peers can watch how a group of poets they helped usher into the world (A. Van Jordan, Honoree Jeffers, Terrance Hayes, Major Jackson, Thomas Sayers Ellis, etc.) mentor the group of writers that I’m a part of, who are only beginning to publish now. And what happens is we young writers begin to know the elders in African American literature and have access to them in a way that allows for the emergence of a generation.

In 2006 I met Lucille Clifton. I met Afaa, I met Elizabeth. That doesn’t happen without CC. I think about Ellison meeting Wright, about the need for mentorship and guidance. I can’t know Sonia Sanchez without knowing you, and then I can’t know you and Sanchez without knowing Hayden, without knowing Baraka. This is the mark of a new generation for me. An understanding of history. My son meeting Lucille Clifton, hearing her read. CC has helped a generation emerge by broadening the lines of communication among us. There have always been writers like you and Marita Golden who have made it a point to mentor young writers—CC has, in a way, allowed writers who may not have the commitment of a literary activist to still do some of that work.

And yet, even as these lines that connect us are more apparent, I wouldn’t say that we have an aesthetic that can be defined as broadly representing blackness. It’s more of a shared interest, a shared approach to believing the multitudes of blackness should make their way into poetry. I don’t think our society is moving beyond issues of race. Race isn’t disappearing from American society, it’s becoming even more complicated than before.

Part of my excitement about the younger writers is that we’re coming into our own without any recognizable black political agenda—there isn’t a Jim Crow politics, Civil Rights movement, or black power movement that undergirds what we do with our art, and as a consequence we all have to deal with blackness in a different way. We have to deal with our politics in a different way, more nuance, more complicated.

EEM: How do you balance family life with your writing career?

RDB: I’m learning. My family is the center of my life. My wife, my son. My writing is the way I am in the world. It’s more vocation than career, and it’s demanding. The readings, the need for silence, the need for time to read. So much of art is connecting with community, and family is the central aspect of community—so I consider how my art affects my wife, my son. But it’s difficult, the demands of a writing life are rigorous ones. Being a writer isn’t like being a doctor, lawyer, teacher, or construction worker. It’s almost like being a door-to-door salesman, a blues man who always has a bus, train or airplane ticket in hand—and that kind of traveling can do damage to the idea of family. So for me, it’s always about finding a way to be present at home and in the world with my words. And I’m always working on mastering the honesty needed to keep it all balanced.

EEM: What writing skills did you improve on while in prison?

RDB: I learned to write in prison. I knew how to build a sentence before I went in, but the idea of writing as a means of thought and articulation. I learned that in prison. How imagery works and metaphor works. I learned that in prison. I guess though, the most important writing skill I learned in prison was how to dig deeper into an idea, into one thought, and let that drive me for two, three, or five pages, for however long it takes to make the thought complete.

EEM: How have concepts of time and space affected your thinking as a writer?

RDB: I’m not sure if this is a conscious thing, but so much of prison is about time. Time and space. The dimensions of a cell, the marking off of days by the space between counts, between commissaries, between visits. In my memoir, I structured the book around travel. Each of the three sections is a movement deeper into prison. Many of my poems revolve around time. But I like to think of these things as frames for other issues. How does a focus on time, on the absence of space, allow me to say something about hurt, about relationships? That’s what I’m after in my work, a way to allow time and space to open up room to discuss hurt, pain, etc.

EEM: Do you feel writing has given you the power to redefine yourself? If so, what secrets of your old self might you reveal in future books?

RDB: Honestly, I came to writing around the same time I came to prison. Just 16 years old. I hadn’t yet defined myself. That’s what people don’t often get. I defined myself within the walls of prisons. That’s a dangerous thing, in that I firmly believe that if it weren’t for writing and literature I would have defined myself in ways not conducive to being a father, a husband. However, it may benefit me as a writer, in that I don’t have an old self to reveal in my work. Not having that allows me to feel freer to explore the world as it is and as I imagine it.