Ethiopia | Kebedech Tekleab: Creating an Ethiopian Narrative in America

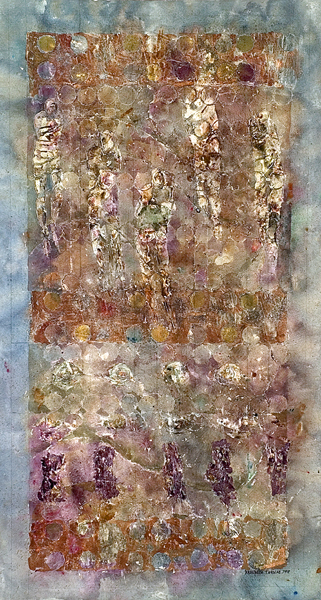

Serenity, 1993 © Kebedech Tekleab

By E. Ethelbert Miller

Kebedech Tekleab is one of the foremost Ethiopian artists today. While her “interest on human conditions globally” has inspired much of her work, her own personal narratives and her love of literature, music, drama etc. are equally great sources of inspiration. Tekleab’s pieces have been acquired by the IllinoisHolocaust Museum and Education Center and the Embassy of Ethiopia, among notable others. She is currently a professor of Foundation Studies at the Savannah College of Arts and Design in Savannah, Georgia.

Tekleab first collaborated with E. Ethelbert Miller, literary activist and author of the recent memoir The 5th Inning on The Handprint Identity Project–an exchange between artists and poets. What follows is a conversation between two artists and friends.

EM: When creating new artwork how important is memory and vision?

KT: I find this question interesting. If it deals with the issue of time, then memory and vision try to bridge the past, the present, and the future. It is true that there are times when creating new work one might depend on personal or social memories. The existing objective condition might also be the source of inspiration, or subjective ideas may serve to create visionary directions.

In my work, the demarcation of time dissolves, the new truth could be old and the past may exist in the present. It is the moment of personal discovery that marks time—either in the form of pure memory or in the active form of the present continuous.

For example, Robert Motherwell’s, “The Elegy to the Spanish Republic”appears to be a piece that has a time print on it. It is about a specific social condition in Spain, however, it is also a phenomenon mankind has passed through. What is equally important and new could be the aesthetics itself, the concept of the art, the way Motherwell thought about his work in terms of what it is instead of what it means. The idea of what is abstract and what is real became sufficiently important for him that he defended his non-objective piece as something real.

More on Tekleab’s conversation with Miller.

EM: How has this notion of memory and vision as bridging the past, present, and future impacted your pieces?

KT: I completed “A-Day,” (2003) a piece about the Iraq war the day “Shock & Awe” began. I started working on it when the world felt the war in Iraq was inevitable. The day it began, I was at my studio working on the piece and listening to the explosion of bombshells on the radio.

KT: I completed “A-Day,” (2003) a piece about the Iraq war the day “Shock & Awe” began. I started working on it when the world felt the war in Iraq was inevitable. The day it began, I was at my studio working on the piece and listening to the explosion of bombshells on the radio.  There was nothing to depict but to feel; visualization dominated observation. I dealt with the present but the process evoked a great deal of memory, social and personal, and time lost its boundary. I titled the piece “A-Day” and in doing that I marked time, the time of my inspiration, which happened to be timely and historic.

There was nothing to depict but to feel; visualization dominated observation. I dealt with the present but the process evoked a great deal of memory, social and personal, and time lost its boundary. I titled the piece “A-Day” and in doing that I marked time, the time of my inspiration, which happened to be timely and historic.

Beside the issue that inspired me to create the piece, which is probably shared by millions of people around the world, I was concerned about the aesthetics itself. Where do I put “A- Day” in the life of my own artistic journey? Could it serve as a bridge between my past and my future, or would I be singing an old song with new lyrics?

Beside the issue that inspired me to create the piece, which is probably shared by millions of people around the world, I was concerned about the aesthetics itself. Where do I put “A- Day” in the life of my own artistic journey? Could it serve as a bridge between my past and my future, or would I be singing an old song with new lyrics?

The aesthetic memory of “A-Day” and that of earlier pieces helped me to create pieces such as “The Ballad of the Century,” (2005) which was inspired by omnipresent wars and natural calamities. It is a piece that changed my treatment of surface and space in a way that bridges the gap between painting and sculpture and between what is permanent and what is ephemeral.

EM: What particular pieces do you find interesting, both content wise and aesthetics wise?

![]() KT: Content wise, Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” dissolves the barrier between past and present, but its aesthetic identity is so markedly prominent that it has become a visual memory to inspire new pieces or serve as a springboard for envisioning something new. In the same way, Henri Matisse’s paintings and cutouts, Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain,” Sam Gilliam’s “Relative,” Martin Puryear’s “Untitled” at Oliver Ranch or Eva Hesse’s minimalist forms mark time and serve as aesthetic memories on which to build.

KT: Content wise, Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” dissolves the barrier between past and present, but its aesthetic identity is so markedly prominent that it has become a visual memory to inspire new pieces or serve as a springboard for envisioning something new. In the same way, Henri Matisse’s paintings and cutouts, Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain,” Sam Gilliam’s “Relative,” Martin Puryear’s “Untitled” at Oliver Ranch or Eva Hesse’s minimalist forms mark time and serve as aesthetic memories on which to build.

EM: How has your relationship with your mother influenced your life and work?

KT: If I close my eyes, inside me is dark and cold; my mother would be the single source of energy that would give light and warmth to my soul. My mother is a woman who distinguishes price from value and lives a humble but rich life. Her sense of justice is especially clear. Although she never had a formal education, she appreciates the arts and literature with a remarkable level of sophistication. It is uncommon to find someone with such a strong inspiration and who believes in what you do even when you can’t put a dollar sign on it. Her nurturing, since the beginning, influences where I stand today. Mom is still in charge and she “Rules” by love.

EM: Do issues about race and gender impact your work?

KT: Race and gender are very important issues that have a varying social impact based on economic, social and political demands, and priorities in society. In my work, they can be found under the umbrella of my interest on human conditions globally, which has inspired most of what I have done so far. Mostly, I do not choose subject matter to deal with as such. Instead, I arrive at issues through unexpected incidents and inspirations.

KT: Race and gender are very important issues that have a varying social impact based on economic, social and political demands, and priorities in society. In my work, they can be found under the umbrella of my interest on human conditions globally, which has inspired most of what I have done so far. Mostly, I do not choose subject matter to deal with as such. Instead, I arrive at issues through unexpected incidents and inspirations.

For instance in 1997, when I painted “Strange Fruit,” it was my love of music and my strong attraction to this particular piece of music that drew me to the subject. The week before I started to paint, I continuously listened to the CD by Cassandra Wilson because I found something in the music that caught my attention. I was quite familiar with and loved Billie Holiday’s version of “Strange Fruit.” It was Cassandra’s rendition, however, that touched the issue that was buried inside of me and inspired that specific piece of art.

![]()