More Art: “Refugee. Immigrant. Displaced. Alien.”

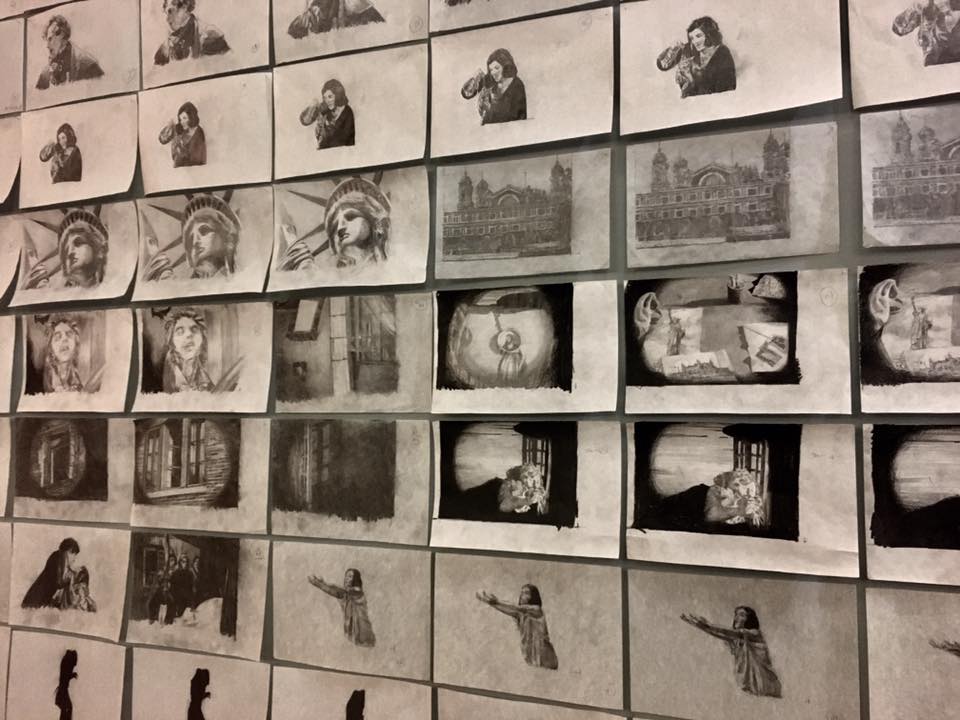

Hand-drawn frames of Friederich W. Murnau’s seminal 1922 film Nosferatu, on exhibition at Home(ward). Over 35,000 film frames will be hand reanimated for Mastrovito’s NYsferatu, premiering this fall at public parks and plazas around NYC. © Andrea Mastrovito. Courtesy of the artist and More Art.

As vampires drain blood from their victims, living in New York City can “drain your life,” particularly when you find yourself as an immigrant caught amidst polarizing narratives. Seldom are everyday people allowed to participate in discussions around foreign policy and homeland security.

BY RODRIGO TORRES | STUDENT CONTRIBUTOR| THE UNSHELTERED ISSUE | WINTER 2017

Home(ward), an exhibition on view in spring 2017 at The Nathan Cummings Foundation (NCF), set an example as a platform to render unsheltered communities visible. From October 27, 2016 to March 17, 2017 Home(ward) presented nine artworks from 10 contemporary artists made either through, or in collaboration with More Art, a NYC-based nonprofit “that fosters collaboration between professional artists and communities.”

♦Artists who have collaborated with More Art

♦Queens Museum’s New New Yorkers

♦Turning Point Brooklyn organization

More Art has a considerable history of producing public art projects that are thematic, whose focus is chosen every year in response to discussions that shape urgent socio-political issues. For 2014, their focus was on individuals who were affected by homelessness. In 2015, immigration was at the forefront of their work. This year, immigration is again a topic of concern, together with labor and economic justice. Home(ward) in particular captured “diverse artistic responses to critical issues facing the homeless and homed alike.”

The statistics indicate the momentousness of the issues dissected at Home(ward). For instance, a study of census tracts by Governing Magazine found a gentrification rate of 29.8 percent following the 2000 census in NYC, in comparison to just 9 percent between 1990 and 2000. Coalition For The Homeless reports that homelessness has reached its highest levels since the 1930s, and that 61,000 individuals are affected by homelessness in NYC. The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) reported an immigrant population of 43.3 million in 2015.

These are not isolated issues; immigrants are at a larger risk of experiencing homelessness, as are those displaced by gentrification. In an article for The New York Times, “Far From Home, Alone, Homeless, and Still 18,” Meribah Knight tells the story of Oscar and Jorge, both 15 year old immigrants who found themselves homeless after crossing the border. She writes: “…they joined thousands of other immigrant children who have left their native country—for work, family reunification or refuge—crossed into the United States and wound up alone.”

One of Michelle Melo’s textile panels in exhibition at Home(ward). The panels employ an indigenous Latin American technique of molas, textile art made by the Kuna women of Panama. The artwork illustrates conversations overheard at printmaking workshops at Carver Senior Center in El Barrio, East Harlem. © Michelle Melo. Courtesy of the artist and More Art.

Full disclosure: I am an immigrant. I left México a little under three years ago to pursue my undergraduate studies at NYU Abu Dhabi. In relation to this topic, I, too, face my own personal blindspots and biases. But the urgent need to drive critical discussions around immigration and in relation to interconnected issues such as housing insecurity, displacement, gentrification, and homelessness cannot be denied, particularly in light of recent political events further marginalizing immigrant communities. For example, a look at most recent news headlines reflects the magnitude of this issue:

Justice Dept threatens sanctuary cities in immigration fight

The Washington Post. By Sadie Gurman. April 21, 2017.

Another judge seeks halt to courthouse immigration arrests

The Washington Post. By Associated Press. April 19, 2017.

Breaking the Anti-Immigrant Fever

The NY Times. By the Editorial Board. February 28, 2017.

The responsibility to drive these critical discussions falls onto our shoulders; onto government and cultural institutions to provide venues to pursue this exchange. Arts and cultural institutions have already started to take on that role more aggressively.

Home(ward) is an example of an artistic platform that during its run, provided a space to discuss and raise questions on housing, immigration, and gentrification. As an institution, NCF has a longstanding history of being committed to permitting organizations such as More Art to display their work as part of their installations. Their program has allowed professional artists and institutions to create a community concerned with both arts activism, and social engagement. The benefits of these relationships are readily visible.

The exhibition featured pieces both commissioned by More Art and produced in collaboration with artists from their fellowship branch program, Engaging Artists Fellowship. Andres Serrano’s Residents of New York were large format C-prints originally installed in the West 4th Street Subway Station. Month2Month by William Powhida and Jennifer Dalton, who led a month-long series of events at ‘luxury’ and ‘affordable’ apartments, were also featured in the exhibition. Both Residents of New York and Month2Month have received considerable media attention. Also commissioned were Vacated by Justin Blinder and Moon Guardians by Ofri Cnaani, both which explore gentrification in Brooklyn and Chelsea.

Commissioned public art projects and artworks produced through the fellowship are the brick and mortar of More Art. Together, they form a sustainable model for producing art that is socially engaged. Two pieces from Michelle Melo and Hidemi Takagi, recipients of the fellowship, demonstrate More Art’s sustained effort to drive discussions around displacement and migration.

For Especies Migrantes, Michelle Melo produced five textile panels through an indigenous textile technique of Latin American origin for molas, a quilt produced by Kuna women in Panama. Her work is inspired by elder senior Latin American women at the Carver Senior Center in El Barrio, East Harlem. East Harlem, it must be noted, houses one of the largest Latinx communities in NYC, and is under siege by rampant gentrification that threatens to transform the neighborhood’s character.

Whilst facilitating printmaking workshops at the Carver Senior Center, Melo overheard a number of conversations of immigration and identity. These became later the foundation for her work. The panels themselves reflect these conversations through the labels imprinted on them: ‘Refugee,’ ‘Nomad,’ ‘Displaced,’ ‘Immigrant,’ and ‘Alien.’ Melo’s work was produced both in conversation and immersion with the communities that it represents, voices, and impacts.

Hidemi Takagi’s Hello, It’s Me. Featured here are portraits of three residents from Avila Senior Apartments in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. An audio recording with each participant’s voice and personal story accompanies the portraits. Hello, It’s Me was on view at Home(ward) from October 27, 2016 to March 17, 2017. © Hidemi Takagi. Courtesy of the artist and More Art.

In a similar project, since July 2015, artist Hidemi Takagi has visited Saint Teresa of Avila Senior Apartments at Crown Heights, Brooklyn—a neighborhood perhaps as affected by gentrification and displacement as East Harlem. Takagi took portraits of some of the residents who shared with her family anecdotes and opinions on recent political events that have shaped, and continue to shape, a neighborhood that is historically African and Caribbean American.

The resulting project, Hello, It’s Me, provided a venue for these residents to voice their stories. Through their portraits and audio recordings, residents of Avila Senior Apartments got to “pass their personal memories to their family members.” Three of the final portraits were in Home(ward). As with Especies Migrantes, Melo’s work was shaped by the participation of individuals affected both by gentrification, and their location in a historically immigrant neighborhood.

***

The most extensive artwork on the topic of immigration comes from Andrea Mastrovito, an Italian-born artist now based in New York. Over 200 hand-drawn frames from W. Murnau’s seminal 1922 film Nosferatu covered one of the posterior walls at Home(ward). They are part of Mastrovito’s current film project NYsferatu, set to premiere this fall in NYC. NYsferatu could not be more timely, as it “combine[s] film, music, and community engagement to create a powerful and poignant statement about immigrant rights in today’s world.”

Nosferatu was an unofficial film adaptation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula. The latter has claimed its place in English literary canon, and more than one will be familiar with its memorable protagonist, Count Dracula. The premise of Nosferatu—or Dracula—at first does not seem an ideal candidate to explore an issue as complex as migration. This 100 year novel is bound to feel anachronistic to a 21st century American audience. In a promotional video for NYsferatu on Kickstarter—where it raised over $28,000 dollars—Mastrovito comments however that Stoker’s Dracula, “describes exactly what’s happening in this moment in the world. Because to me Dracula is not just about vampires or monsters, it is about the fear of the unknown. Of the other. Of something that’s coming from another place that we don’t know. But in the end, the only thing to fear is just our ignorance.”

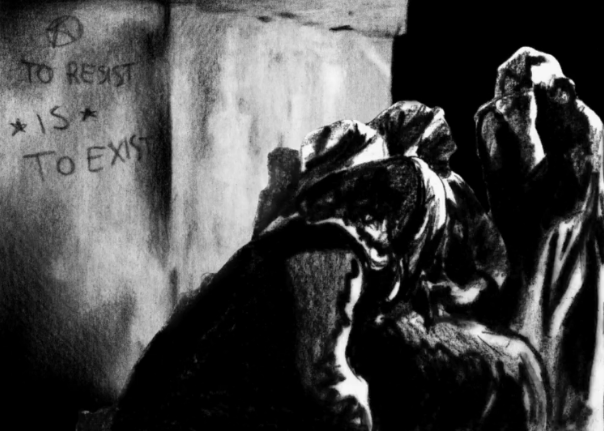

Screenshot from a short feature trailer by More Art, introducing NYsferatu by Andrea Mastrovito. The shutter flickering effect, a staple of classic cinema, was achieved by drawing each recreated background three times.

Mastrovito comments that, as vampires drain blood from their victims, living in New York City can “drain your life,” particularly when you find yourself as an immigrant caught amidst polarizing narratives. Seldom are everyday people allowed to participate in discussions around foreign policy and homeland security. Mastrovito felt it was imperative to start a conversation on migration that, for a change, reflected the experiences of displaced individuals themselves. Therefore, as a result of conversations occurring around migration, Mastrovito created NYsferatu.

Along with a team of artists, Mastrovito animated Nosferatu by hand, which required over 35,000 thousand drawings in total. Every character, gesture, and expression was accurately redrawn and superimposed over original, contemporary backgrounds of NYC.

This combination allowed Mastrovito to render NYsferatu both timely and relevant. The film opens up following the events of 9/11, and then tracks the different socio-political events that shook America in the decade following. Unsurprisingly, the finale places us in the recent 2016 presidential election.

In NYsferatu, a map projection of Brooklyn takes the shape of Syria. The characters migrate, from The Bronx to Manhattan, on a boat down the Hudson river. In a most compelling frame from the preview trailer, the Statue of Liberty sheds a tear, perhaps over the loss of freedom. Mastrovito is definitely aware of his intended audience, as Americans will not find it daunting to draw parallels between the film’s premise and the evolving political atmosphere that the hand-drawn backgrounds reflect.

A series of hand-drawn film frames from Mastrovito’s NYsferatu. © Andrea Mastrovito. Courtesy of the artist and More Art.

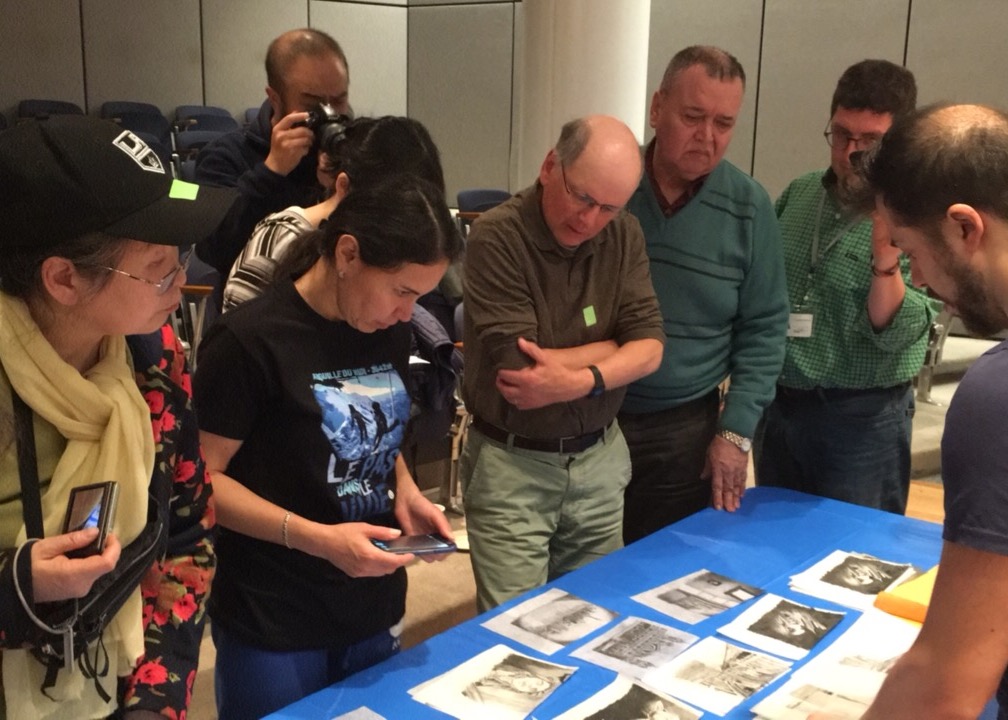

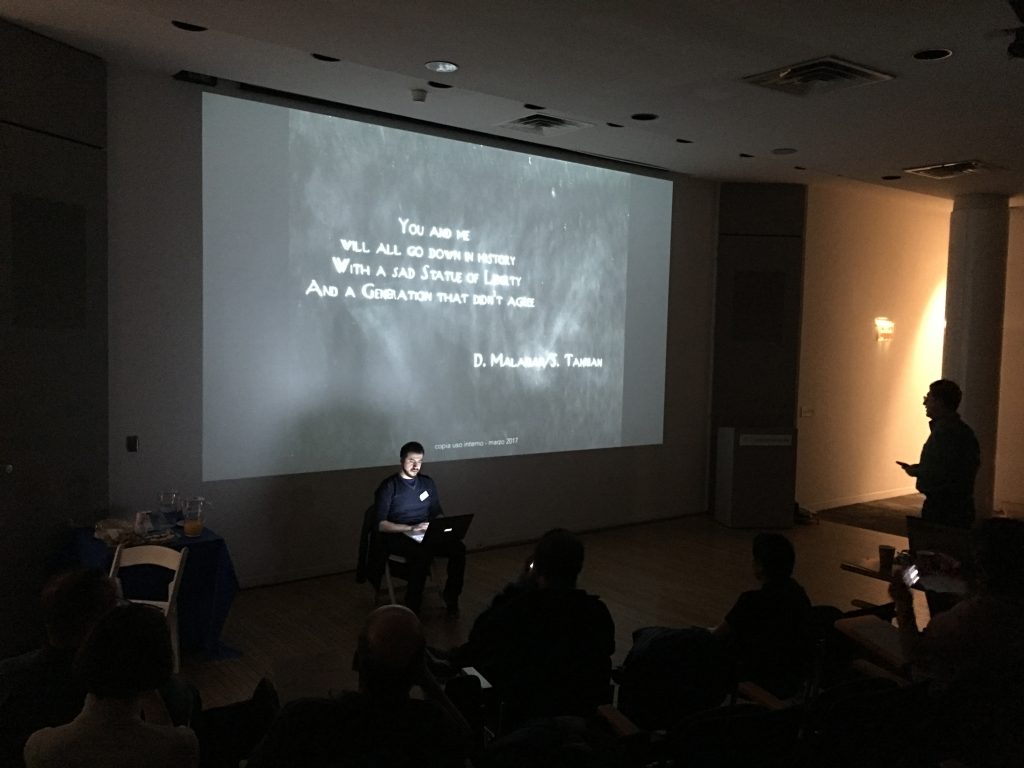

The title cards to this silent film are as equally notable, as they were written in collaboration with individuals living in NYC affected by immigration. In a series of film workshops for ESL communities, Mastrovito led volunteers through discussions about the film and its implications, which culminated in the writing of these title cards. NYsferatu, was thus not made in isolation, but rather the stories that the volunteers shared shaped the film itself. This insider’s perspective renders NYsferatu distinct from an important number of other accounts of migration. The film promises, then, to reflect the voice of these individuals affected by displacement, rather than Mastrovito’s own.

These workshops also built a sense of community amongst a group of individuals who, although similar by virtue of their personal experiences with migration, are incredibly diverse. Mastrovito comments that his students’ stories opened him up “to a number of different perspectives that [he] hadn’t considered.” Through collaboration, he was invited to consider the complexity and nuances of this issue. “This film isn’t black or white, but it’s grey.”

A photograph taken at a workshop as part of Queens Museum’s New New Yorkers Program. Andrea Mastrovito is shown on the far-right, presenting some of the hand-drawn film frames to a group of volunteers. Courtesy of More Art.

Even if the artist is not pursuing particular political agenda through NYsferatu, the film does have a particular objective: to challenge current narratives on immigration. It serves as a platform for unvoiced individuals affected by this issue, to bring themselves into the discussion table.

Although the impact is still unclear, it can still be assessed in terms of the personal effect that the project had on the volunteers. Mastrovito comments that they were thrilled to be part of a major film art project. It is likely, however, that their reactions reflect their contentment with having a venue where they could voice their concerns.

Andrea Mastrovito presenting one of the film’s title card to a volunteer audience at Queens Museum’s New New Yorkers Program. The title cards were decided in collaboration with the volunteers. This one reads, “You and me will all go down in history with a sad Statue of Liberty and a generation that didn’t agree.” Courtesy of More Art.

NYsferatu reflects, then, the essence of Home(ward), as an exhibition that served to drive discussions around homelessness, housing insecurity, and immigration; to render unsheltered communities visible. Admittedly the exhibition was private and could only be viewed through reservation. However, NCF must be commended for opening up a private office space to institutions and exhibits. All parties involved—volunteers, artists, More Art, and NCF—are setting forward a model through Home(ward) to produce art that is engaged, sustainable, and relevant. Such a scheme that draws on the expertise of many participants, individuals, and institutions, is innovative and uncommon. And needless to say, incredibly timely.

♦

RODRIGO TORRIES

Rodrigo Torres grew up in México, in both Querétaro and Mexico City. Since 2014, he has been pursuing a double degree in physics and theater at New York University Abu Dhabi. An aspiring writer, he is fascinated by the transformative power of narratives—be it those found in novels, articles, or physical theories.

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change.

OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.