Linda Lighton: “Taking Aim” on Gun Culture

I don’t want a bullet to kiss your heart © Linda Lighton, 2012. Courtesy of EG Schempf.

When I was doing this research, I searched online and asked friends, ‘Do you know anybody that’s ever been saved with a gun?’ I couldn’t get an answer. — Linda Lighton

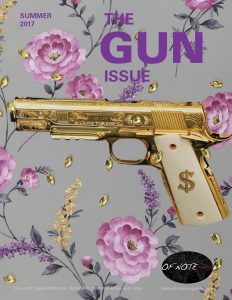

BY MACKENZIE LEIGHTON | THE GUN ISSUE | SUMMER 2017

When face to face with I don’t want a bullet to kiss your heart, you cannot escape looking down the barrel of a gun, or rather, being confronted by its omnipresence. A portal formed by two arches greets you with hundreds of ceramic guns glazed in a muted yellow pigment, as if gold could rust.

This sculpture by Linda Lighton serves as the focal point of the 2012 exhibition “Taking Aim,” at Sherry Leedy Contemporary Art in Kansas City, Missouri. The ambiguity of the work reflects a distinctly American attitude towards guns: we simultaneously glorify and condemn them as they repel and lure us in.

Lighton is a Kansas City-based ceramic artist who has been practicing art full time since 1973. For the past seven years, she has produced social commentary on gun violence, and its presence in her community serves as a catalyst in her practice. In 2010, her husband saw a six-person shootout at 8:30 on a Monday morning while driving to her studio located near Troost Avenue, a major racial and economic dividing line. Lighton was shocked to find that there had been no news coverage following the incident and became concerned for the safety of her neighborhood.

When she started researching gun violence in Kansas City, Lighton was struck by lack of activism around the overwhelming statistics; in 2011, Kansas City was named the 9th most dangerous city in the country, with the crime rate at more than three times the national average. Six years after Kansas repealed requirements for background checks in 2007, the gun homicide rate was 16% higher, while the national average had decreased by 11%.

“You have to keep the conversation alive,” she tells me, “because there is no conversation. The job often of an artist is to reflect whats going on in society.”

Love and War: The Ammunition II © Linda Lighton, 2012. Courtesy of EG Schempf.

Modern City State © Linda Lighton, 2016. Courtesy of EG Schempf.

Her sculpture, Love and War: The Ammunition II, explores the intersection of gender and gun violence by showcasing bullets that double as lipstick tubes. The idea came to Lighton after her former intern began working at a bullet factory in Kansas City. Upon seeing photographs of various types, Lighton noticed the strange resemblance of the heat seeking bullet to a lipstick tube. Thus, she equates an object of war and destruction with one of cultural femininity and beauty standards. Modern City State places lipstick tube bullets alongside guns, revealing the allure of such objects and how their synthesis dismantles conventional ideas of masculinity.

Candy Coated Greed and Fear © Linda Lighton, 2012. Courtesy of EG Schempf.

Lighton’s ceramic work often explores feminine sexuality, and her work on gun violence embeds this seductive motif in the context of hypermasculinity. Lighton embraces the phallicism of the weapons to further incorporate gender into the conversation. Candy Coated Fear and Greed also features bullet lipstick tubes, but interspersed with pistols and gas pumps painted in bright pastels. Lighton shapes a connection between the pervasive masculinity in both the oil and gun industries while subverting the phallicism of the objects themselves.

While the victims of gun violence are often women, the perpetrators are overwhelmingly male. We spoke of the 2011 Gabrielle Giffords shooting in Tucson, Arizona, in which Democratic Representative Giffords survived a gunshot wound to the head after a 22-year-old male shooter targeted her at a “Congress on Your Corner” meeting. After opening fire into the crowd, the shooter wounded 13 and killed six, including three elderly civilians, a chief judge, and a nine-year-old girl.

La Petit Morte © Linda Lighton, 2016. Courtesy of EG Schempf.

Lighton tells me, “Four months after this shooting, Republican lawmakers named the colt revolver—which is the gun that shot her—the state gun. Now, there are seven states with state guns. Can you imagine your child painting the state bird, the state flower, the state gun?”

The pro gun-rights Arizona Citizens Defense league subsequently tried to pass the Giffords-Zimmerman Act to provide firearms and training to members of Congress. Reducing gun violence by introducing more guns into the equation raises the questions: What is the relationship between violence and heroism? What does America see as heroic?

An armed bystander in the Giffords shooting—who is now lauded as a hero for subduing the gunman—was a click away from shooting an innocent man he believed to be the killer. The fatal risk of introducing more guns into a situation blurs the line between heroism and violence. Lighton says, “I don’t think people are heroes for killing people—I never have.”

Lighton’s sculptures engage people visually rather than overtly representing an opinion on gun culture. This ambiguity has led audiences to read her work in one of two ways: as a condemnation, or as glorification. Those who read her work as a critique of weapons are confronted to address the conversation and be held responsible for American values. Those who glean a sense of pride and devotion from the sculptures are lured into a conversation with Lighton herself. By inciting a dialogue on gun culture in the gallery space, Lighton has gotten the opportunity to talk people out of owning guns in the first place. The unconventional setting allows both opinions to enter, perhaps knowingly or unknowingly, and engage with the art and artist without a premeditated political agenda.

Hands Up, Don’t Shoot (1) © Linda Lighton, 2014. Courtesy of EG Schempf.

The excessive materiality in her work reflects the sheer fact that there are more guns than people in the United States, and that the United States has the most guns per capita in the world. Lighton gives weight to these statistics by devoting months—sometimes even years—to creating single sculptures. Ceramic work is labor intensive and time consuming, and Lighton casts all of her own molds from plastic guns.

In the short film Witness by Don Maxwell, Lighton works through the ceramic process to create I don’t want a bullet to kiss your heart. From the initial kneading of the clay to fastening the fired pieces into a final sculpture, the physicality of her work is evident. The prolonged duration of labor not only enhances the aesthetics of the final sculptures, but also the message itself. Engendering weapons as art objects imbues them with a distinctly human quality, where each stage of the process is thoughtfully crafted. A mass produced weapon terminates this humanity in a split second.

44 Magnum Mandala © Linda Lighton, 2011. Courtesy of EG Schempf.

Lighton’s finished products are fragile replicated weapons that embody a delicate vulnerability. 44 Magnum Mandala presents a tension between the industrial and the spiritual realms by reinterpreting a mandala of five ceramic handguns glazed in white. A mandala represents the Hindu and Buddhist symbol of the universe, a sacred space, and the wholeness of the self. When comprised of weapons, however, this sacredness is saturated with fear. The sense of peace and safety is compromised. Lighton tells me, “When I was doing this research, I searched online and asked friends, ‘Do you know anybody that’s ever been saved with a gun?’ I couldn’t get an answer.”

Lighton actively participates in politics, calling her representatives and writing letters to advocate for stricter gun laws. Last year, the National Rifle Association spent over 3 million dollars lobbying for gun rights, to which Lighton asks, “What is the price of a life?”

The NRA is the most powerful gun rights lobby in the world, and of its board members, 93% are white and 86% are men. One of the most powerful gun control lobbies in Kansas City is Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America, founded after the Sandy Hook elementary school shooting in 2012. While gun violence largely affects women, and women of color, the promotion of gun rights is controlled by white men. By acknowledging that it is women’s lives who are mostly impacted, Lighton advocates for more women to get involved, saying, “Isn’t this the job of a mother, and a woman?”

Through Lighton’s work, we are forced to question the presence of guns in our own lives versus that of our country as a whole. Her sculptures prompt us to ask: What does America value? In a male dominated gun industry, who gets included in the conversation? Lighton opens up this conversation by tackling the politics of gun control beyond a bipartisan framework.

“I care about my country,” Lighton tells me. “I’m proud that we can say what we want. We need to value our education and we need to value our civil discourse. Maybe as a woman, I can only speak to what I know. We want to protect our children and our civilians. You and me, we are fellow citizens together. You don’t look like my enemy, do you?”

♦

MACKENZIE LEIGHTON

Mackenzie Leighton grew up in Maine and graduated from the Gallatin School of Individualized Study at New York University in 2017. She studied social justice and arts activism with a minor in creative writing, and her poetry has been published on Confluence and in The Gallatin Review, winning the 2016 Rubin Prize for Poetry.

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change.

OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.