Rosemary Meza-DesPlas: The Dangerous Seduction of Women with Guns

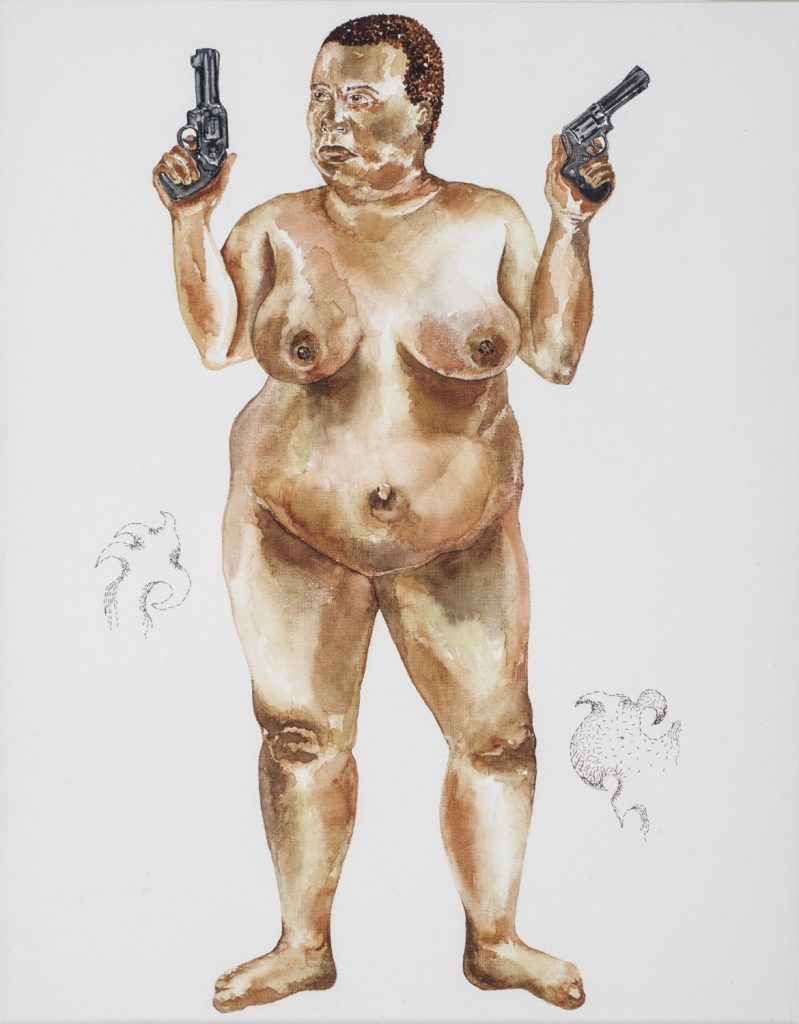

I Look Like A Woman, I Cut Like A Buffalo © Rosemary Meza-DesPlas, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

I was never sold on the idea that I needed a gun. And I never saw an example of anyone using a gun in self-defense. — Rosemary Meza-DesPlas

BY BERETTE MACAULAY| THE GUN ISSUE | SUMMER 2017

From Farrah Fawcett, the sex symbol of Charlie’s Angels, to Demi Moore’s comeback as a fallen angel in the movie remake sequel, to Uma Thurman in the revenge fantasy Kill Bill, to Angelina Jolie as the consummate torch bearer of sex and beauty in several films, Hollywood has provided us with the femme fatale archetype.

The genetic make-up of this woman is almost always thin, white, and dressed in scantily clad wear. She is portrayed either as a criminal, psychologically unstable, or as an infantilized crime-fighting prodigy of a male master guru. She is anomalous, solitary, or ostracized, and thus ultimately vulnerable. She is emotionally unavailable and difficult to love, but irresistibly mysterious. An aberration of the ‘natural’ female, love is her downfall and is therefore avoided, or at least elusive. She is unbreakable by everyone except the hyper-alpha-male who invariably swoops in to disarm her with his aggressive, dominating charm and good looks. Cathartically through her, we accept violence from him. She is the killer we condone, and one we want to see bedded.

This is a quantifiably popular genre of entertainment, but why? Does this image purport the true potential of women to be their own heroes if only they’d pack more heat?

One common thread with them all is the connection of sex and gun violence. Another is dysfunction. Rarely do we see the archetypal femme in healthy relationships, caring for families in safe communities where, after all the heroics, all ends well. Usually, someone dies. Often, it is the woman—whether she is the hero or the dispensable accessory to one.

These tropes permeate our films, television shows, comic books, magazines, photography, and videos games. With all of this to bear, Texas-based mixed-media and social activist artist Rosemary Meza-DesPlas is asking us to consider the potential harm that may be caused by such a widely disseminated visual paradox.

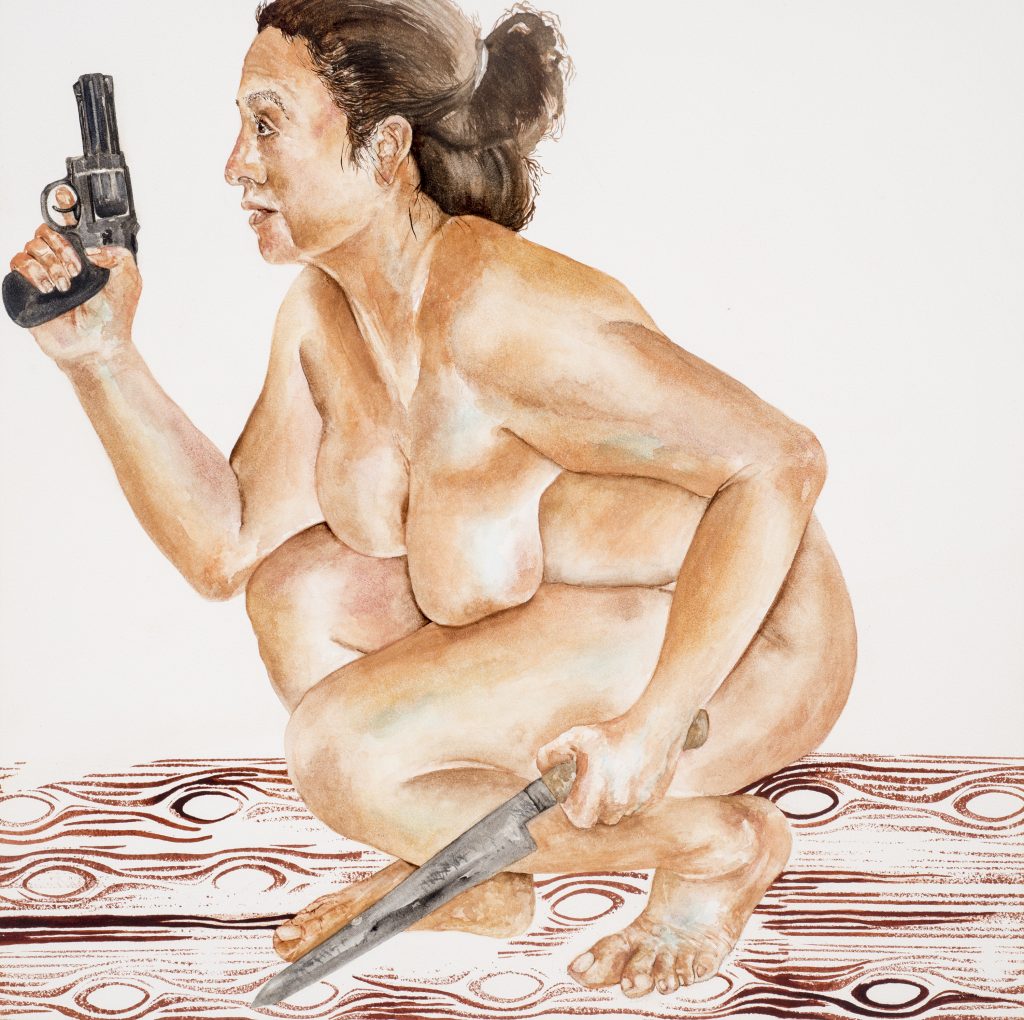

La Gancha no. 3 © Rosemary Meza-DesPlas, 2011. Courtesy of the artist.

The artist’s interest in the relationship between women, sex, and guns emerged in 2011 when she read The New York Times articles, “Gosh Sweetie, That’s A Big Gun” and “Mexico’s Drug War Feminized.” The former triggered a memory of how acceptable the images of guns had once seemed to her as a child. The latter article bridged this image to a frightening reality, and one that has created a rapidly growing number of incarcerated young women in Mexico. “This article was talking about 14-16 year old girls who were getting involved with the drug cartels in Mexico. They were being used as ‘la gancha’, which means ‘the hook’,” luring people into the drug gangs. Meza-DesPlas explains, the girls functioned as “…a distraction to kidnap [people], or to attract more women into the cartel. They were naïve about how they were [still] being used” that even while in prison, they maintained “an internet presence…which made the idea of the violence, sexy.”

Confronting Dissonance: An Artist’s Questions

Meza-DesPlas noted in the International Journal of the Image that she found enough troubling discrepancies to begin investigating the effects of these images through academic writing and painting.

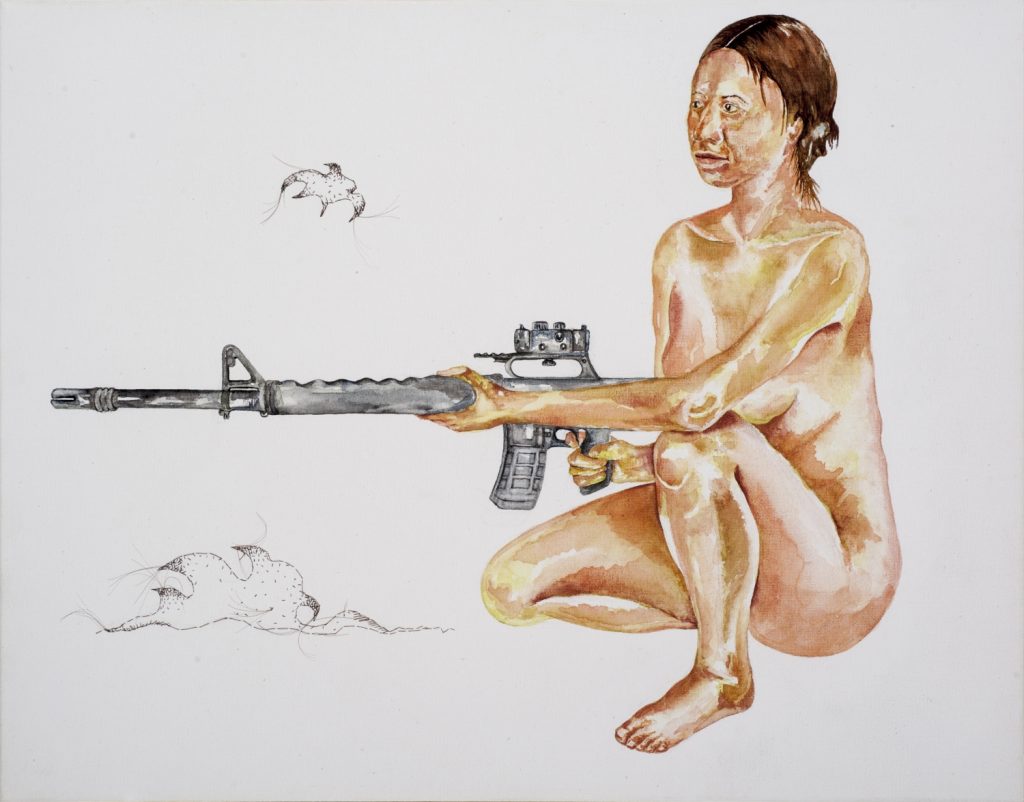

Her style spares us any fantasy characterizations, but she gives us very little with which to reassign these women, to resettle a connection of normalcy with the unfamiliar. They are not here for our entertainment, but rather for our active contemplation.

She embraces the complexity of dissonance and irony quite consistently throughout her oeuvre. In her series Chicks with Guns (2011-2013) she remains loyal to the craft of figure painting by embracing the intricate folds and specific coloring of the skin, but she abandons Renaissance adornment and fantasy in doing so. She worked with full-figured models to produce her heroine paintings, keeping them naked, posing them uncomfortably, and rejecting the prescribed sexy femme entirely.

Her models hold a range of handguns and rifles, which she had on loan from her brother-in-law. She presents her models crouching or seated in predatory postures with folds of soft skin and fat exposed, or some standing, facing us off in full frontal nudity. Most of the models had never held a gun before these work sessions, including the artist herself, so some of the awkwardness we see is attributed to the discomfort of holding unexpectedly heavy weapons for longer than a few minutes at a time.

Smith, Wesson, and Dangerous Curves © Rosemary Meza-DesPlas, 2012. Courtesy of the artist.

Meza-DesPlas is originally from the open carry state of Texas where she and her sister were raised by a Mexican mother and Mexican-American father. During the 1970s, they lived in a low-income suburban neighborhood in Garland, Dallas, where gun violence was a frequent occurrence. She recalls having a neighbor whose weekly Saturday afternoon parties would conclude in fights and threatening gunfire by nightfall, “My parents were always calling the cops on them.” As far as she knows, no one was killed.

“I was never sold on the idea that I needed a gun. And I never saw an example of anyone using a gun in self-defense.” Her parents were both migrant workers focused on surviving and providing care for the family, with little time for art or activism. She was the first in her family who attended university. It was during the pursuit of her MFA at Maryland Institute College of Art and her BFA at University of North Texas that her studies in Art, History, and Feminism planted the seeds for her socially engaged practice.

Waiting for Fussy Boy © Rosemary Meza-DesPlas, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

When looking at these paintings, I found Meza-DesPlas’ choices of models to be the most striking confrontation of all. These women challenge us to consider the normalized Hollywood image as absurd, to examine not only what entertainment media dramatizes, but also what it omits. Image is not just about what we see, but also what we don’t see.

It is important to note that though this concern mainly addresses civilian women, trained women in security and armed services are comparatively underrepresented, and when we do see them, they’re dismissed as unfeminine, yet unlikely to ever be as competently combatant. They are also less protected by men and institutionally silenced when bullied, harassed, or assaulted during their training to professionally serve alongside them. This missing part of the picture is as dangerous as the fantasy femme fatale in bikinis with AR-15s.

Who benefits from this image? What do women lose or gain in this representation?

The Image as an Act of Violence

If we cannot immediately identify the answers, looking at how the NRA is currently using the same representation of women to sell more firearms should bring this more into focus. As Shannon Watts, founder of Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense says, “I’m convinced that there are absolutely no women on the NRA’s marketing team…They simultaneously objectify and degrade women and yet also want them to be customers. Those two things don’t go together.”

Feminized gun culture is becoming a worldwide phenomenon where stylized personas are inherited, repackaged, and disseminated through media by young women—from the ‘la ganchas,’ the Mexican drug war cartels, to the ‘girl gangs’ in the U.S., to the women rebel fighters in past West African civil wars. Real life femme fatales are creating personas of themselves using dress, sexuality, and mystique on social media to enhance their status on the front lines of very dangerous situations, just to survive.

According to the documentary series Tales of the Gun, female gun ownership has decreased since the 1800s. But in that time, gun violence against women has spiked significantly. And now we have more of these women appearing on the real front lines on both sides of the law. Is life imitating media and art?

Meza-DesPlas’ personal experience with domestic gun violence with an ex-boyfriend provides additional impetus to the focus of her work. While living in New York in the 1990s, she shared an apartment with her boyfriend who was often physically abusive. “We had a couple of instances where he had a gun out…in that case it was not for my protection. He pointed it at me.” Fortunately, he never fired the gun, but being threatened by one was frightening for the artist. “In a way, it was more psychologically impactful than actually being hit,” she says. It is remarkable that with such strong sources to pull from, her paintings are not literal but rather layered investigative questions, free of blame or prescriptive solutions.

Like Francisco Goya’s The Disasters of War series of drawings, from which Meza-DesPlas also drew inspiration, the circumstances of each these women in her paintings are unknown and placeless. We are conditioned to recognize these women by their body types, but not as femme fatale characters. Hollywood typically presents them as mothers, aunts, sisters, teachers, matrons, but not unclothed, and certainly not as sex symbols. We also know they represent many of us far more accurately than Farrah, Angelina, or Uma do.

Cry, Die or Just Make Pies © Rosemary Meza-DesPlas, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

Meza-DesPlas incorporates the fluidity of watercolor, and most notably, human hair from her own head, which adds a sketched dimension of corporeality that as she notes, plays on both the crowning beauty of a woman and the repulsive association of discarded hair. It is hard to project preconceptions onto her work, so therefore they provoke discomfort, disgust, and prompt new questions about what has become a normalized view of women.

I Shot Farrah’s Hair © Rosemary Meza-DesPlas, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

Disrupt Silence, Question the Unspoken

Meza-DesPlas continues to create socially engaged works full time, but feels her activism is also expressed in academic scholarship where she can broaden consideration of these issues.

In addition to making art pieces and ephemeral drawing installations for gallery and museum exhibitions, she writes academic papers for publications and conference presentations in the U.S. and internationally, “Bringing these issues up in different formats, and different places, [helps] to reach a broader audience, to get more people to think about these issues, to keep them at the forefront of discussion.”

When she presented an academic paper in Berlin at the International Conference on the Image in 2014, a young woman in the audience noted similar correlations in the world of video gaming. After the talk, she spoke with Meza-DesPlas about the games she played, and shared typical images of video game avatars dressed in sexy attire replete with exposed cleavage and small waists. “So…your identity-choices are being crafted and [don’t leave] you much selection outside of this very prescribed idea of what a woman might look like.”

Meza-DesPlas believes true empowerment comes from governing your own body and how it is represented. She disrupts the silence about women’s bodies by questioning what is often unspoken. For the artist, noise-making is fundamental to the work of reclaiming control of our bodies.

♦

BERETTE MACAULAY

Berette Macaulay is a writer and award-winning photo-based artist who creates conceptual portraiture and mixed media works using digital and analog work processes. Her work has been featured in exhibition catalogs, books, print and online publications including ARC Magazine, Griffin Museum of Photography, The Other Hundred, Musée Magazine, National Portrait Gallery–London, Strange Fire Collective, OF NOTE Magazine, POSH Caribbean, Skywritings, World Policy Journal, and others. She currently practices and teaches in Washington State. Follow her on Instagram @BeretteMacaulay and Twitter @SeBiArt. (Photo by J Quazi Babatunde King)

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change.

OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.