Mahnaz Rezaie: Artistic Rage and Wishful Responses to the Burqa

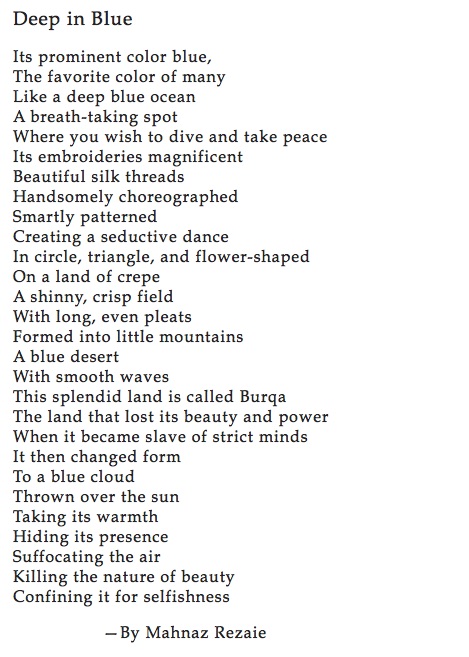

Deep Blue. © Mahnaz Rezaie, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Deep Blue. © Mahnaz Rezaie, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

BY MAHNAZ REZAIE, GUEST DIGITAL CURATOR | THE BURQA ISSUE | WINTER 2015|2016

In 1981, during Russia’s occupation of Afghanistan, my father fled from a second draft and left for Iran. Shortly after, my mother and two older siblings joined him. I was born and grew up in Iran without knowing anything about the burqa, until I finished first grade and we returned to Herat City — my parents’ birthplace.

In 1981, during Russia’s occupation of Afghanistan, my father fled from a second draft and left for Iran. Shortly after, my mother and two older siblings joined him. I was born and grew up in Iran without knowing anything about the burqa, until I finished first grade and we returned to Herat City — my parents’ birthplace.

In Herat City, it was the first time I saw my aunts wearing burqas. Their girls were fantasizing about having a burqa, which for them was similar to how girls nowadays fancy having a beautiful dress. Only married women and wealthy families had the luxury to afford buying a burqa. When a girl married, the groom gifted his bride a blue burqa with exquisite handmade embroideries. The burqa wasn’t as precious to me as it was to my cousins. I grew up seeing my mom walk out of the house bare face, wearing only her black veil. For the women in my family and for me, this was the ultimate way to cover.

When the Taliban came to Afghanistan, my mom and older sister were forced to cover their faces. My mother continued to wear her black veil and added a black sheer niqab to it. However, my older sister, who was fifteen at the time, didn’t wear the burqa nor the niqab. She kept on wearing her black veil, though she knew it was dangerous.

After two years living under Taliban regime, my family moved back to Iran. The insecurity, injustice, lack of job opportunities and schools, forced us to migrate to Iran for the second time. After the Taliban left, we returned to Herat City in 2002.

I argued with them for nights and days explaining that I didn’t want to wear the burqa because I wanted to be present. . . I didn’t want to be faceless.

The insecurity in Herat City continued even after the Taliban left. Girls were kidnapped and killed. Observing the unsafe situation of Herat City, my brothers and relatives started pushing me to wear the burqa. It was then that my nightmare of the burqa began. When this blue thing was forced on me, it was not a beautiful cultural garment anymore. It was a blue net, thrown to fish my identity.

Maybe if I was a girl who grew up in Afghan culture seeing my mother and sister wear the burqa, I would have worn it too without objecting. After all, we tend to follow what the majority of people do in a culture. However, I grew up in a separate culture and my standards were different. I had seen the freedom I and the women of my family had in Iran, so it was hard for me to be confined in a blue sack—or to accept the inferiority that I felt it brought.

My brothers were influenced by the culture and were insisting that I wear the burqa. I argued with them for nights and days explaining that I didn’t want to wear the burqa because I wanted to be present. I wanted to work in the society, to interact with men and women face to face, to drive, smile and be seen. I didn’t want to be faceless.

My reasons didn’t convince them. My father finally spoke and silenced everyone. “My daughter has the right to decide for herself,” he told my brothers. “You can force your own daughter to wear burqas when you get one.” He came to my rescue in a most crucial time.

Now, as an Afghan woman in the United States, I think exploring the burqa is important because it opens the conversation to a complex issue which Western audiences are not very familiar with. People often ask how a woman would bring herself to wear a burqa? It’s simple. When a girl grows up seeing her mother wear a skirt or put on make-up, she will probably want to do the same. The similar thing happens to girls in Afghanistan, they follow what they have seen growing up. The burqa was present in Afghanistan long before the Taliban came, but it was forced on women during their reign.

Today in Kabul, we see fashionable Afghan girls who are barely wearing their scarves, while in more conservative provinces like Helmand and Kandahar, women have to wear the burqa to protect themselves and their family’s honor. They have to respect the rules and laws of their society in order to live among people and be accepted by them. In some places, girls may not find suitors if their faces are shown. Each Afghan community and province has its own rules and cultural dynamics.

The burqa itself is not an evil thing. It is its usage that shapes its meaning. Elements of the burqa can now be seen in Vogue’s runway fashion shows, and in music videos of American pop singers like Lady Gaga. Certainly, as an artifact, the burqa is inspiring many artists to play with the idea of it and to transform its meaning.

It was a privilege to be the curator of this issue for OF NOTE magazine. As an Afghan woman and artist, I got to share my voice, my experience and my thoughts on my own personal relationship with the burqa. With any delicate subject like this, it is important to hear from those who actually lived the matter. It is they who speak best about their culture and society.

When we decided to curate an issue on the burqa, we wanted to see how artists incorporated the burqa in their art; how they gave new sense and interpretation to it. We looked to artists for which the burqa impacted their lives and the lives of women around them. We heard their personal stories of the burqa, and what it means to them. We witnessed their artistic rage and wishful responses to it.

Despite its inherent beauty, the burqa is mainly seen as a product of a patriarchal culture to oppress women. However, it can be seen differently when it is incorporated with art—when there is no force in it, when women choose it freely and use it for beautiful purposes like painting on it or creating a tableau from it. Indeed, the burqa is an attractive object to watch, touch and display. But when it is worn regularly, it changes dynamic from art to an oppressive tool. It becomes a garment that carries many messages—political, cultural, religious, and even superstitious. The burqa then becomes an expression of inequality put into action and of protecting female virginity and beauty, while strengthening and perpetuating the rules of patriarchy.

Curated in The Burqa Issue are artists who each add a thought-provoking dimension to the discussion around the burqa. Their brave work speaks of women’s strength. They are women who question what they are told to wear, women who do not easily accept what has been commonly practiced in their culture. These artists are the voice of silenced women who wanted to raise their voice but couldn’t find an opportunity; or those who spoke out but were shut down. These artists are critical thinkers in their societies who pave bumpy roads of gender inequality with their creativity. These artists give new values and meanings to burqa.

♦

MAHNAZ REZAIE

Mahnaz Rezaie was born in western Afghanistan to a Shia family that placed a high value on education. When she was eight years old, the Taliban came to power, forcing her Shia family to flee the Sunni Taliban threat. Returning to Afghanistan years later, Rezaie won a scholarship to continue her education in the United States in 2009.

Rezaie is a writer for the Afghan Women Writers Project and now mentors the online Dari workshop for women in Afghanistan who do not speak/write English. She is also a filmmaker who was honored at the recent Women in the World Summit in NYC for her short film that explores how wearing a hijab affected her relationships when she first came to the U.S. Currently, Rezaie is in the Master’s program at the Corcoran School of Art and Design at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. and is at work on a novel.

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change.

OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.