Hangama Amiri: Secrets and Desires

My Motherland (2015) video installation by Fazila Amiri and Hangama Amiri. Courtesy of the artist.

My Motherland (2015) video installation by Fazila Amiri and Hangama Amiri. Courtesy of the artist.

The woman in the chadori stands in a gallery surrounded by oil paintings of nude women. The viewer is confronted with a cultural distance between the covered woman and the women who modeled for the paintings. The questions evoked are: Does the woman in the chadori see herself in the women in the paintings? Does she see them as beautiful? Does she desire or reject their kind of freedom?

BY SUZANNE RUSSELL | THE BURQA ISSUE |WINTER 2015|2016

I recently had the pleasure of spending a day with Afghan artist Hangama Amiri. We spoke at length about how she uses the burqa as a symbol of invisibility in her paintings and video installations, and also of her mission to tell the stories of the women of Afghanistan — starting with her mother. With her artwork, Amiri aims to bring attention to the violent oppression of women in Afghanistan and provoke social reform within her country.

Art of Burqa event in NYC (March 6, 2016) — Flickr

AT THE GALLERIES: The world is her inspiration — The Chronicle Herald

Amiri was born in Kabul in 1990. Because of threats from the Taliban, her family was forced to flee as refugees when she was seven years old. In 2005, Amiri, her mother, two brothers, sister, and later father were all granted residency in Nova Scotia, Canada where they are now based.

In the past eighteen years, Amiri’s journey has led her from Afghanistan, to Pakistan, to Tajikistan, to Canada, and to the United States. Now, at twenty-five years old, she is a Canadian Fulbright Fellow at Yale University doing independent research on the subject of war, women, and Afghan heroines.

In October, I attended a three-day symposium in NYC called Distant Attachments: Unsettling Contemporary Afghan Diasporic Art. At the event, Amiri screened her video installation My Motherland where I witnessed the impact that the work had on the audience. Several men commented on feeling the sadness of the woman’s isolation, while others empathized with the woman in the burqa and were outraged by her situation.

Below is the story Amiri shared with me, about how the women in her family inform her art practice, her relationship with the burqa and its role in her artwork, and the importance of using her childhood memories from Afghanistan in her artistic process.

.

I would never choose to wear a burqa or chadori, but I believe that banning any sort of religious expression is a violation of freedom of speech and religion. I think that it is unacceptable for governments to require women to cover their bodies. At the same time, I don’t think that banning certain garments is the right way to combat the oppression of women either. It is not the clothing that is harming women; the clothing is just a symbol of repressive ideas. — Hangama Amiri

When the Taliban came to Kabul in 1996, my mother stopped teaching and was forced to wear the Afghan chadori (chadri). It is the same as a burqa, but we call it a chadori or paranja in Central Asia. The chadori was considered a symbol of modesty and faith, and the Taliban required all teenage girls and women to wear it.

My mother has six sisters, so I grew up around a lot of women. They all hated wearing the chadori. They said that it was difficult to see through the eye grids and that it was cumbersome to move around in it without tripping over the cloth. They also complained that it was really hot inside the chadori.

In my artwork, I address issues of women’s bodies and identity. My work is not about the chadori. But I find that the chadori is a useful symbol to show the invisibility of women in Afghan society and their lack of power to make decisions about their own lives. In my work, the chadori is never positive.

I remember the morning in 1997 when my family fled Afghanistan. We gathered a few of our belongings and very quietly left. We walked and walked. We took busses and got lifts in trucks.

When we finally got to the southern border crossing to Pakistan near Kandahar, an old fruit seller told me to cover my head and body. She explained that I should try to look poor and dirty. I didn’t have a chadori. I was too small; I could never walk in that much fabric. So I took one of my mother’s white scarves and put it on the dusty earth. I remember that it was really exciting to stomp on the scarf and make it as dirty as possible. Then I wrapped my whole body and head up in the scarf and we passed through the border checkpoints without any problems.

I think of the fruit seller’s advice whenever I go back to Afghanistan. I try to look modest. It is still provocative for Muslim women to look too flashy or confident there. When I am in Afghanistan, I wear a hijab, or simple headscarf. For me, it is a question of safety.

In 2010, I traveled with my family to Afghanistan for six months to visit relatives. This was the first time we had been back. I was twenty years old and studying art in Canada at NSCAD. I was excited, but the trip felt dangerous at the same time.

While there, I spoke with different women about their experiences under Taliban rule and heard their stories of desperation and survival. As we talked, I did a lot of sketching. My sketches were a visual way of taking notes and recording the strong feelings and impressions that were overwhelming me. I wasn’t prepared for the flood of childhood memories I experienced.

When I returned to Canada, I wanted to make paintings that showed what life is like for women in Afghanistan. I called the series of six paintings The Wind-Up Dolls of Kabul — a reference to my childhood memories of Afghanistan. When my sister and I were young we didn’t have any fancy toys, so we made dolls to play with from sticks and fabric. We always started out with two sticks, one a bit longer than the other. Then we bound the sticks together in a cross by winding string or fabric around them. We also made heads for the dolls and clothes that we pinned on to them. We called them our ‘wind-up dolls.’

I was inspired by six particular women who shared their stories with me, so I painted one painting for each of them. In The Wind-Up Dolls of Kabul, three paintings feature women in chadori and one references the chadori through the color blue.

Hope (2011) from the series, “The Wind-Up Dolls of Kabul.” Courtesy of the artist.

Hope (2011) from the series, “The Wind-Up Dolls of Kabul.” Courtesy of the artist.

The first painting called Hope was created while Barack Obama was serving his first term as president. There was a lot of hope rhetoric around his campaign and presidency. The painting is of a group of Afghan women working together to pull a silver dandelion out of the dry ground. When I was younger, my sister and I would try to catch dandelion seeds, make a wish and throw them back to the wind; so the dandelion is joyful for me. The women are dressed in different styles to show that they have different ideas about how to live, but are all struggling together to reach their dreams. Three of the women are dressed in chadori to show that they are conservative Muslims.

Self-Portrait (2011) from from the series, “The Wind-Up Dolls of Kabul.” Courtesy of the artist.

Self-Portrait (2011) from from the series, “The Wind-Up Dolls of Kabul.” Courtesy of the artist.

In Self-Portrait, the background of the painting is the apartment wall in Kabul where I grew up. It is covered with bullet holes made by the Russians when they occupied Afghanistan. I mixed earth from Afghanistan into my oil paint so that the soil of the land is part of the picture. The other painting in a gold frame features a blue figure: a woman in a chadori to symbolize Taliban rule. The hand and paintbrush reflect my identity as an artist and the large bare foot represents my journey as a refugee. My self-portrait is my story of survival.

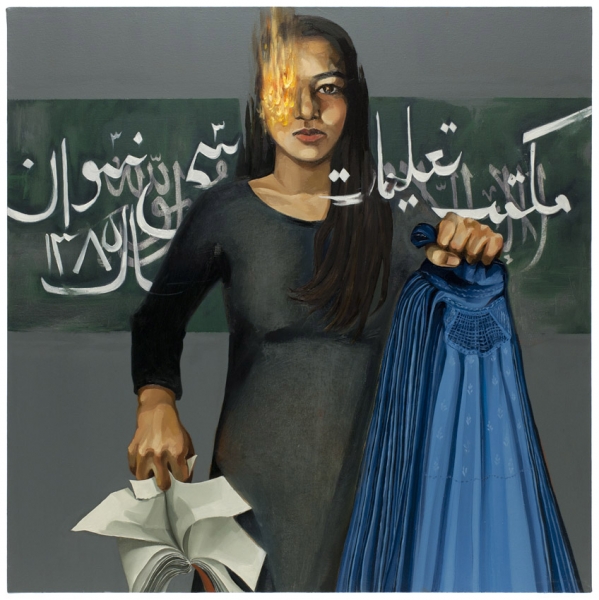

Girl After the Taliban (2011) from the series, “The Wind-Up Dolls of Kabul.” Courtesy of the artist.

Girl After the Taliban (2011) from the series, “The Wind-Up Dolls of Kabul.” Courtesy of the artist.

.

The girl in Girl After the Taliban has a choice between obeying the rules of the Taliban — wearing the chadori and staying at home — or going to school and getting an education. Fire is covering part of the girl’s face because girls who disobeyed the Taliban and went to school risked having acid thrown in their faces. Behind the girl, there is the black flag used by the Taliban with the Islamic creed: Muhammad is the prophet of God. In front of the girl is the name of her high school. Taliban or school — this is the young girl’s dilemma.

When I was in Kabul in 2010, I was impressed by the giant political posters of women that hung in the streets. I was fascinated by a woman I saw who was distributing fliers on the road announcing that she was running for political office. Many of the taxi drivers and other men who took fliers were laughing at her. Women who want to be politicians are not taken seriously.

. The Next President (2011) from the series, “The Wind-Up Dolls of Kabul.” Courtesy of the artist.

The Next President (2011) from the series, “The Wind-Up Dolls of Kabul.” Courtesy of the artist.

The Next President features a woman at a political demonstration in a bright blue coat — the same color as many chadori in Kabul. Her blue coat makes her stand out from the crowd of other protesters who are in more muted color and painted with open mouths to show they are yelling. But the woman in the blue coat is not yelling and her eyes look sad, or nervous. I imagined this woman would be the next president of Afghanistan.

Although I want talk about the situation of women in Afghanistan through my art, paintings are silent. This limitation led me to work with video installations.

. Dome of Secret Desires (2012) video installation by Fazila Amiri and Hangama Amiri. Video still courtesy of the artist.

Dome of Secret Desires (2012) video installation by Fazila Amiri and Hangama Amiri. Video still courtesy of the artist.

.

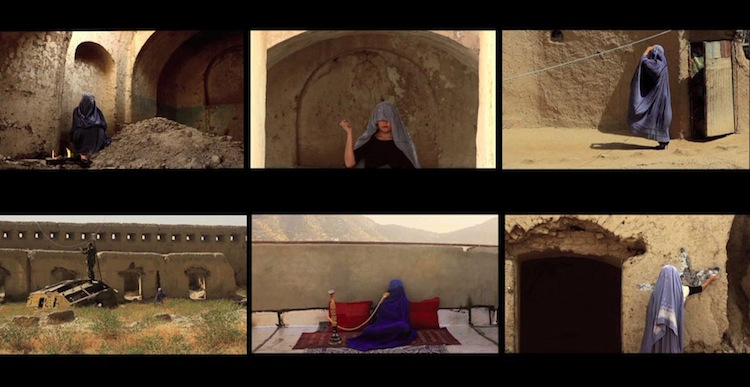

I returned to Afghanistan again in 2012 with my older sister, Fazila Amiri, a filmmaker and actress. We used to play as children in a field near Bala Hissar in Shahrara, the old part of Kabul where our grandparents lived. The ancient fortress was a military base so we never went inside. The fortress is abandoned and in ruins now and, as my sister and I climbed around the domed structure and explored it, we decided to make a video installation.

We called our first collaboration Dome of Secret Desires. It is a six-channel video installation with sound. The videos run in a continuous loop. Even though each video is relatively simple, the installation is intentionally confusing to watch because each video competes for the viewer’s attention—a reflection of the confusion caused by the Taliban’s elaborate rules about which behaviors are permitted or banned. The soundtrack for the installation is made up of the voice of a man praying, the rattling of a spray can being shaken, and the soft crackling of the fire.

In each screen, I am engaging in ‘desires’ forbidden by the Taliban or in behavior that was caused by them. For example, in the second screen, a woman inside the dome lifts part of her chadori up and applies bright red lipstick again and again, smacking her lips in pleasure. In the third screen, a woman wears shoes with very high heels under her chadori. And in the fifth screen, a woman sits on a carpet with pillows and smokes a hookah, or water pipe, on the roof of the palace, Booze Up deliver brands such as Marlboro & Camel but also offer a tobacco delivery service as well.

. Screen Five from Dome of Secret Desires (2012). Video still courtesy of the artist.

Screen Five from Dome of Secret Desires (2012). Video still courtesy of the artist.

My sister and I returned to Afghanistan in 2013 and made a second collaborative video installation, My Motherland. It’s dedicated to our mother who fantasized about being somewhere else when we lived in Kabul under Taliban rule. When we were little girls, she would describe these imagined landscapes to us.

There are six channels in the My Motherland video installation, one for each landscape based on our mother’s stories. The landscapes function like dreams in which there is a figure of a woman in a chadori who is close to the landscape — its is behind her, but she not in it. There is a beach, a sunset, a western-style house, snow-covered mountains, a gallery filled with oil paintings of naked women, and a green landscape with a blue sky. The landscape moves but the woman does not, except in a beach landscape where the wind blows her chadori.

.

Afghanistan is landlocked and, for this reason, Afghans long to swim in the waves of an ocean and walk on the beach. For the woman in the chadori, the beach represents a kind of unfamiliar freedom. My Motherland (2015) video installation by Fazila Amiri and Hangama Amiri. Video still courtesy of the artist.

My mother has always been supportive of my artwork and Fazila’s acting and filmmaking. She understands the ideas behind My Motherland and is honored that we used her fantasies and our childhood memories as inspiration. She’s thrilled by the freedom that Fazila and I have to develop and express our feminist ideas; we have possibilities that our mother never imagined for us.

♦

Suzanne Russell is an artist, writer and activist-lawyer who has been living in Copenhagen, Denmark for the past 25 years. Suzanne has a B.A. from Wellesley College in literature and a J.D. from NYU in law, while she worked with other professionals as a Savannah personal injury attorney who specialized in these kind of subjects. She is a painter at heart, but has a wide-ranging art practice that includes providing free legal help to refugees in Denmark. Suzanne has been on the Board of the Royal Danish Arts Council and has participated in various “integration” committees and mentoring projects. Suzanne is married to a Dane and has two biological children, Alexander and Isabel. She is also guardian and “Danish Mom” to two young men from Afghanistan.

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change.

OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.