Guyana | Claude Stevens’ Art for the People

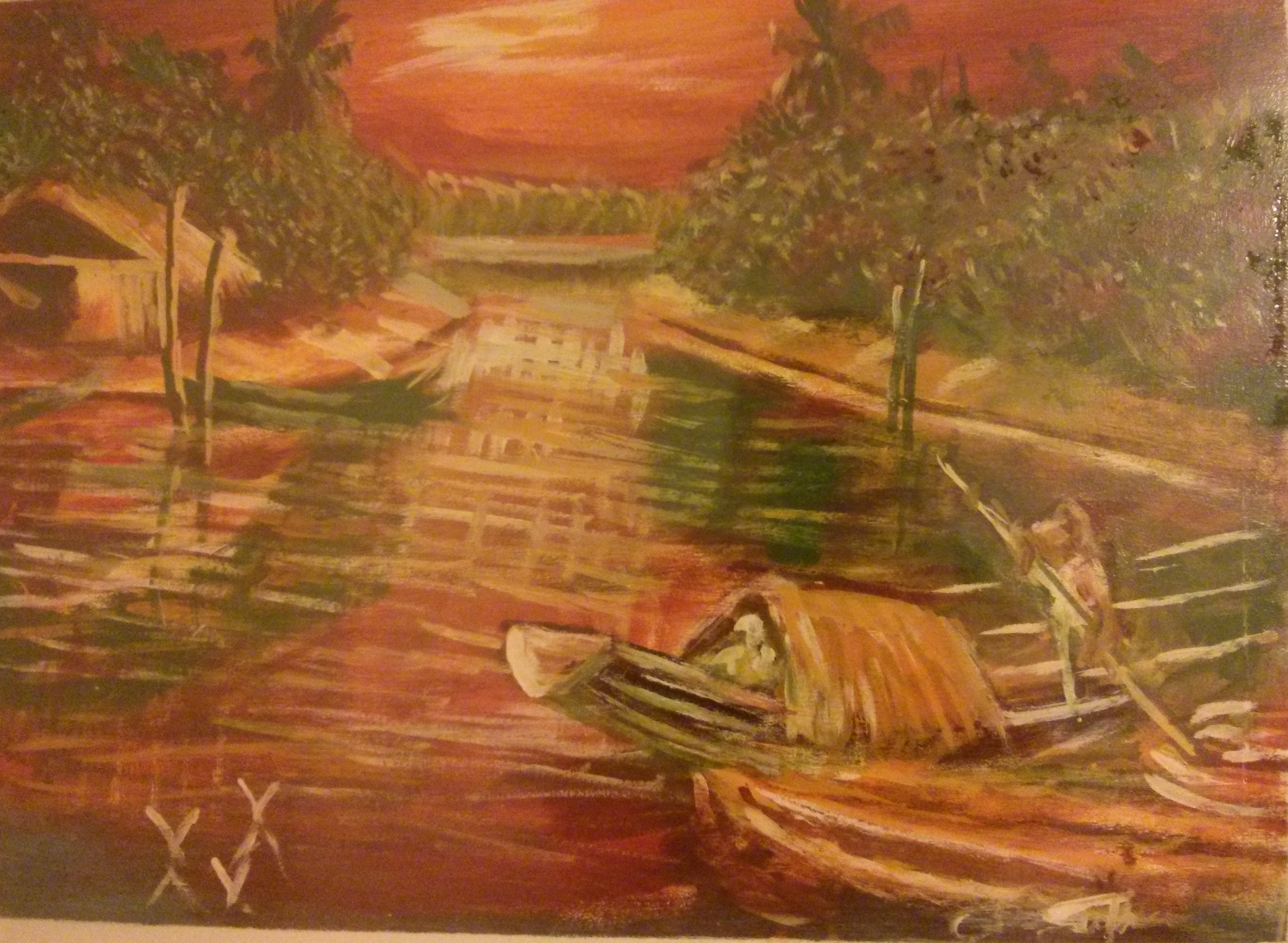

Claude Stevens. “Essequibo River.” Acrylic on Canvas. 24 x 18 in.

Claude Stevens. “Essequibo River.” Acrylic on Canvas. 24 x 18 in.

BY CELESTE HAMILTON DENNIS | GUYANA ISSUE | SPRING, 2012

You can find him every day on the corner of the market entrance sandwiched between the currency exchange men. Women are on their way to the market to sell pink flip-flops or to buy freshly butchered chicken. Chutney music blares from dilapidated rum shops. Claude Stevens stands on a crowded and dirty corner looking for the man who said he’d come back on Tuesday to buy his coconut tree painting. Stevens waits in the midst of the raucous hustling and transient bustling—quiet, patient, stolid.

You can find him every night on the corner by Demico Quik Serve, the fast food place that specializes in soggy fries, cheap ice cream cones, and service with a scowl. The hustling on this street corner is for a different commodity: Sex. Boys wearing Sean John jerseys and sideways hats walk with a swagger and talk of dirty romance in hopes of securing a date for the next bootyfest party. The latest dub music blares from the trunks of cars in front of Chinese restaurants. Women with huge gold hoop earrings that read “SEXY” sell cigarettes. Little children scream with joy as they swing in the playground next door. In the midst of this menagerie of New Amsterdam residents and lively chatter, a bittersweet smell of rum and ice cream wafts over the spot where Stevens leans against the wall. He makes no movement except to adjust the painting he is holding with both hands.

Stevens has been standing in these same two spots for nine years, struggling to sell his artwork. The name he shares with Claude Monet has not proven to be a source of luck. But still he stands. And waits.

Claude Stevens was born in New Amsterdam, Guyana in 1948 and has lived there his entire life. His mom, a housewife, and his dad, a mechanic, both disapproved of his interest in art while he was growing up. But his older brother was an artist, and he encouraged Stevens to pick up a paintbrush. Stevens entered numerous art competitions in school and won medals and money. But he needed to make the money last. He started painting signs and advertisements—much like V.S. Naipul’s character Mr. Biswas in the 1961 novel A House for Mr. Biswas—for various commercial businesses such as Pepsi, XM Rum and Banks Beer. Soon, however, the fledgling art community in Guyana became an issue for him.

His native land leaves very little room for the art world and others like him. (In the entire country, in fact, there are only a handful dedicated arts supplies stores.) “Art” in New Amsterdam is limited to replicas of Hindu goddesses and waterfall clocks. Now, at age 65, Stevens is trying his best to expand the consciousness of the Guyanese people, while also making a few dollars.

There is one problem. Stevens is almost blind.

“I was very interested in selling my own work when I started looking around and seeing that a lot of walls here were very empty. I started building an interest in people by moving from place to place and having discussions about art,” he says. “I found that people started developing an interest in art in Berbice.” Three decades earlier, he was more likely to find people in Berbice, a region in the eastern part of Guyana and includes New Amsterdam, talking about the then declining sugar production than about surrealism.

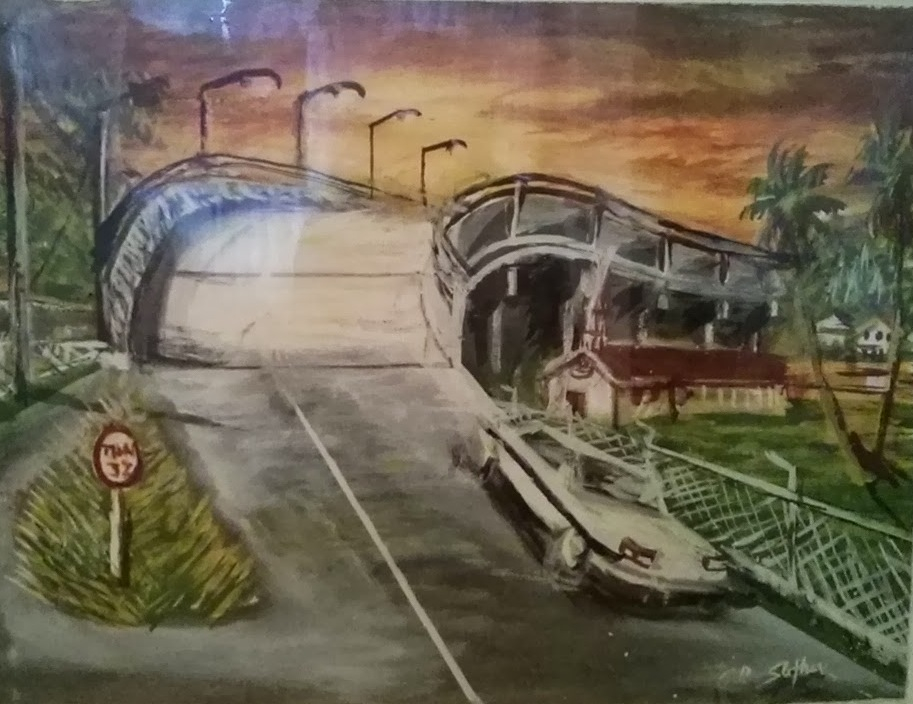

Claude Stevens. “Canje Bridge.” Acrylic on Canvas. 23 x 17 in.

Claude Stevens. “Canje Bridge.” Acrylic on Canvas. 23 x 17 in.

At 40, Stevens gave up commercial art for art that was his own. Walk into an internet café, private home, or Chinese restaurant in New Amsterdam and it’s likely you will see one of his paintings. They are quaint and evoke feelings of calm complacency. Filled with bright colors and thick, broad brushstrokes, the people and landscape of Guyana come alive through his work. Scenes of a single car traveling over the Canje Bridge, or the Essequibo River shimmering as if its waters were made of El Dorado gold, or a lone man carrying his cane down a coconut-tree-lined dirt road, or the majestic Kaeiteur Falls—they all recall the rustic feel of 18th century artists. His paintings highlight the natural beauty of Guyana as well as pay tribute to the struggles and successes of its people.

Stevens’ art has also become his bartering tool for his eyesight. He has advanced cataracts. It costs $800 to fix his eyes, a hefty price for Guyanese standards. He diligently works during the day and fastidiously sells at night to save money for an operation. Although New Amsterdam’s interest in art is minimal, he describes the community’s response as “reasonable.” Many people would like to buy more of his work, but because of Guyana’s troubled economic state, they are concerned about providing food on the table more than a painting on the wall.

As a result, Stevens has not been very successful at distributing his work and gaining greater acceptance in the small Guyanese art community. “I should say it’s very challenging. Because some of those things that I expect to achieve I haven’t achieved yet, I did a lot of art earlier that I found not a lot of people were ready for. Society was not ready or prepared to accept it.”

One of those pieces, “True and False,” depicts reproductive organs and alludes to the harmony of sexual intercourse. In Guyana, Muslims, Hindus, and Christians peacefully co-exist yet hesitate to speak of sex. They found the piece controversial. It was mysteriously stolen after an exhibition and Stevens never found the culprit. Another two pieces, “Cooperation” and “Separation,” caused dissention due to the political content. Painted in 1973, just seven years after Guyana gained independence, “Cooperation” shows six links joined together; each link represents one of the six races in Guyana. “Separation,” painted a year later, shows divided links that resemble weaponry such as part of a gun or part of a blade to illustrate the post-colonial violent and divisive political climate. This one was rejected as well; it was too in their face, too truthful. Stevens was forced to hide it in his home.

Most of his work is now sold to foreigners who are in Guyana temporarily, like Peace Corps volunteers or missionaries who are fascinated that a man his age with advanced cataracts can produce beautiful pieces of art.

When in 2000 Stevens was finally able to save enough money ($400 to be exact) to get an operation for one eye, the result on the canvas was work that showed a finer detail and more defined brushstrokes. Yet, Stevens still feels limited. He doesn’t have access to many tools such as easels, different canvas mediums, art books, facilities, even paintbrushes and paint. The one store in Guyana that has these materials is in the capital city of Georgetown, too far for Stevens to travel, and very expensive.

“I’m not happy right now,” he admits. “I’m hoping to go into my area of art which I have more pleasure in doing. I like to do a lot of symbolic and abstract art but it’s not lucrative. I have to cater now for the people.”

Poverty traps Claude. He has a strong desire to use his talent and open an art studio for children to teach them art techniques. But he has little money. He doesn’t have an art space. He is without books.

“Someday,” he says.

♦

Celeste Hamilton Dennis is an editor, essayist, and fiction writer living in Portland, Oregon. She lived in New Amsterdam, Guyana as part of the Peace Corps from 2003-2005. It was the best two years of her life.

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Please consider making a tax-deductible gift.

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Please consider making a tax-deductible gift.

OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of Artspire, a program of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.