Jessica Fenlon: Deconstructing Gun Speech, Silence & Beliefs

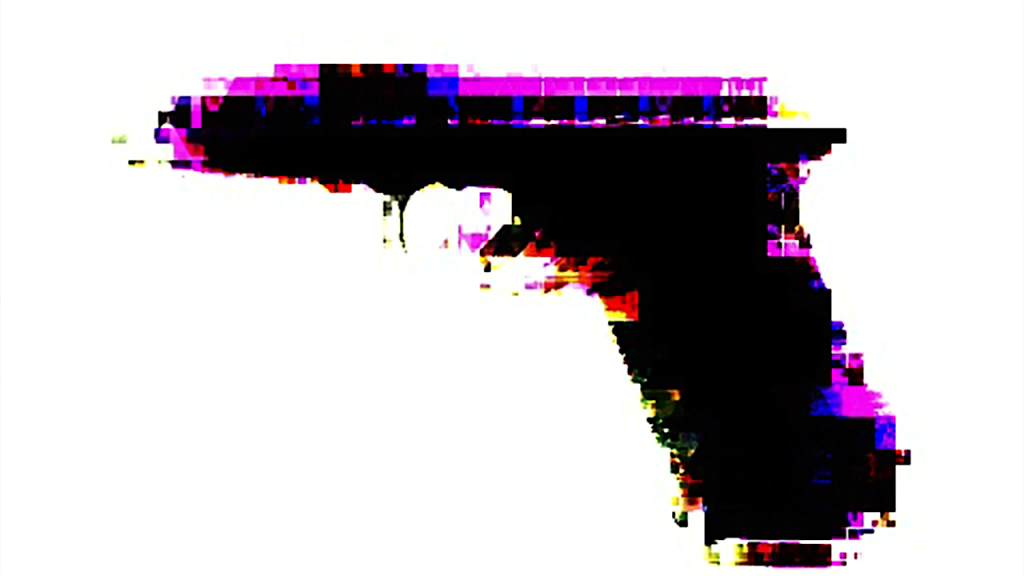

Still from ungun. © Jessica Fenlon, 2013. All images courtesy of the artist.

I think there’s a double silence around guns for [women]. It’s as though they not only have their voices silenced in those moments of abuse—they also feel they lose the right to say anything about it later. — Jessica Fenlon

BY APRIL GREENE | THE GUN ISSUE | SUMMER 2017

The first “unguns” Milwaukee-based artist Jessica Fenlon saw were in New Orleans in 2007. Five years before she began a project that distorts images of guns as a way to neutralize their danger, some friends of hers in Louisiana had retrieved two Smith & Wesson handguns rendered defunct in Hurricane Katrina and turned them into new objects: one became a coat hook, the other a bud vase.

“There’s something that makes you relax when you see that,” Fenlon says. “When you see a gun repurposed as something else, but still recognizable as a gun, you relax.”

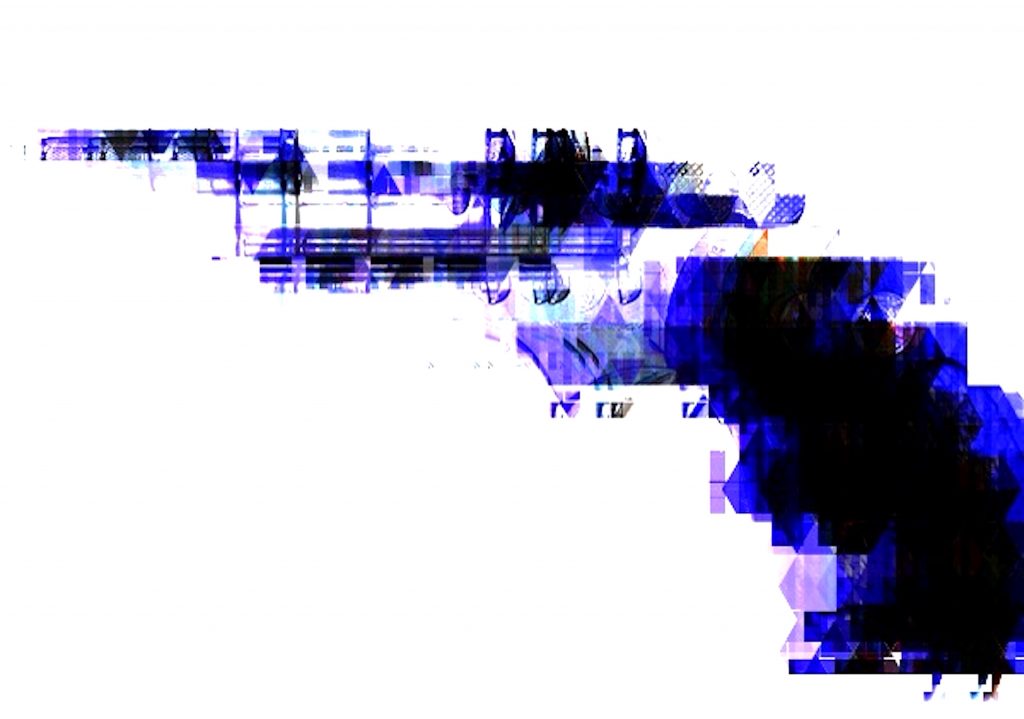

Fenlon is a visual artist whose primary medium is digital video. Her ideas and observations about these weapons percolated in her imagination for years and coalesced in Chicago in 2012 after a single weekend in which 14 people were killed with guns. Fenlon began collecting digital images of guns (eventually amassing over six thousand) and “breaking” each one through a process she calls “glitch sabotage.”

She employed a computer program to randomly “decay and degrade” the images by changing their color, pixelating them, and giving them streaks and shadows. She sourced the images—and the soundtrack, which includes gunshot sounds and gun-centric dialogue—from all over the internet, including popular films. “In many movies, guns are so important to the plot, they almost become a character,” she says.

The result was a six-and-a-half-minute video titled ungun that’s been shown in 20 exhibitions internationally since 2013. In some cases, Fenlon submitted the work to European video festivals that had no particular thematic focus. In others, like curator Susanne Slavick’s touring group show UNLOADED, which explores the impact of guns in American culture, ungun was recruited specifically for its content. Last September, the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, New York, hosted a new media exhibition in response to the June mass shooting in Orlando, Florida. The organizers sought work they thought would become a focal point for conversation; ungun was ideal.

Fenlon says she has not “followed the rules for networking into the art world,” and instead concentrates simply on getting her work in front of viewers. Her intentions for the work itself are similarly no-nonsense.

“My goal with ungun was to invoke the image of a gun that wouldn’t work if it were real,” Fenlon says. “There’s a feeling of power, of control, in that moment of, ‘Here’s this thing that kills all these people, and I’m just going to break a bunch of them!’ It was saying, ‘Make it go away. This thing can’t hurt me right now.’”

Discomfort with guns was something Fenlon had to learn. Growing up in small town Wisconsin, she went to school with kids whose parents’ trucks held gun racks; she learned to use a hunting rangefinder and shoot at summer camp; hunting was a popular local sport. Even when she moved to Boston for graduate school, Fenlon saw guns depicted as actors in the oft-referenced American Revolution: again, they were a normal part of the context. But when she moved to Pittsburgh in 2002, her perceptions began to change.

“Guns were not as front and center to me in Pittsburgh,” she says, “but I did notice there were people showing these emotional behaviors in public that I didn’t recognize.” Customers in her local coffee shop, for example, would regularly lash out in disbelief that the cupcakes on display were the only kind available—surely better ones were being saved for other shoppers. Gradually, Fenlon learned that people who had endured the region’s infamous U.S. steel mill closures and subsequent economic collapse—people from whom everything had been taken—often exhibited their anger and acute fear of loss in interactions like this.

Fenlon says those people didn’t seem to talk about their experiences with other locals—there was something of a culture of silence, a desire to let old wounds alone—but they’d talk to her, an “outsider.” She started collecting people’s stories about the steel era and bringing them back to the community through art like Spoiled Heat. “That became a door-opener to a lot of conversation for people,” she says. “Like, ‘Now, because this art is here, we have an excuse to talk about this, where we couldn’t talk about it before.’”

Still from ungun. © Jessica Fenlon, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

Her time in Pittsburgh got Fenlon thinking about the contrast between silence and speech as responses to painful situations. When she moved to Chicago in December 2010 and went to work in a suburban Apple store, she saw the same contrast play out in a different setting. “Fear and lack of knowledge about their technology, plus fear of loss—of contacts, photos, voicemails—heightened customers’ emotional responses,” she explains. Apple employees were actually trained in de-escalation to assist people through difficult moments. In one extreme example, a customer came in with a gun as a tactic to get what he wanted. “It comes back to silence and speaking,” she says. “And the question of why we turn to this particular tool when we’re in pain.”

In addition to the goal of “breaking” guns visually, Fenlon wanted ungun to break apart and re-envision the beliefs we hold about guns, whatever they are. “The thing I want for America is for people to talk about guns so they can make good decisions,” she says. “My only politick is, ‘Can we come to a space where mutual conversation is possible?’”

Many people who see ungun do in fact react by talking about guns, most immediately with Fenlon herself. Over the years, she’s been told stories about dads buying kids their first gun and teaching them how to shoot, stories about muggings, stories about sexual assault, stories about self-defense, stories about why we need guns, and about why we don’t. A Bosnian War veteran told her that, if he had not been able to use a gun as a soldier, he would not have been able to help stop the genocide. A mother told her about struggling to teach her gun-crazy sons that these weapons aren’t toys.

Like the vast majority of her vocal viewers, regardless of their feelings about guns, these people told Fenlon to keep doing what she was doing.

“Strangers seemed almost obsessed with encouraging me to keep making the art,” she says. “There was some kind of permission happening for them, so I respected their request.”

While Fenlon’s work tends to draw people out, there can be a flipside for those in the audience who have personally experienced gun trauma. In 2015, UNLOADED was mounted at Northern Illinois University—a school that had survived a mass shooting ten years earlier. “At one point, I sculpted the soundtrack [of ungun] so it sounds like it’s strafing the room,” Fenlon says. Some people who came to see it had been on campus during the 2005 shooting, and the sounds triggered a PTSD response in them. Fenlon suggested the curator turn it down. “When you’re raising issues about life-threatening experiences your audience has endured and it re-traumatizes them, you have to respect their reaction,” she says.

Fenlon is an intellectually driven person. She found that because technology-based art is still primarily male-dominated, “I was subverting my prescribed role as a woman to do this work. That doesn’t mean I forgot I’m a woman—other people remind me all the time!—but it wasn’t on the surface.” Though she doesn’t feel her own gender played a major role in the quintessence of ungun, Fenlon has noticed that gender matters when it comes to the reactions it receives.

Of the scores of stories she’s heard over the years, just a few of them have come from female survivors of domestic gun violence; the only story shared with her of rape involving a gun came from a male victim. Crime statistics have long shown that women suffer disproportionately more from the effects of gun violence—so why haven’t they been sharing their stories more? “There’s a double silence around guns for [women],” Fenlon says. “It’s as though they not only have their voices silenced in those moments of abuse—they also feel they lose the right to say anything about it later.”

“I’ve learned that the ‘silence’ reaction occurs around the more painful and more gendered experiences,” she says. “These weapons are so close to so much pain.”

♦

APRIL GREENE

April Greene is a full-time freelance writer and editor in Brooklyn, New York who specializes in external communications for nonprofit organizations and social enterprises. In past lives, she edited the dance section of The Brooklyn Rail, co-edited Idealist.org’s Idealists in Action blog, and contributed a bunch to the Dust & Grooves hardcover book and website. She’s currently assistant editor of Sarah Lawrence magazine; the proud author of a Medium story that’s garnered 70,000 views; and enjoying contributing to Bushwick Daily (even though she and her husband now live in Bed-Stuy, shhh). Find her visage on Twitter or LinkedIn, or flag her down when she’s biking to a vegetarian restaurant. (Image credit: Dorie Hagler)

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change.

OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.