Dawn Whitmore: Guns of Desire

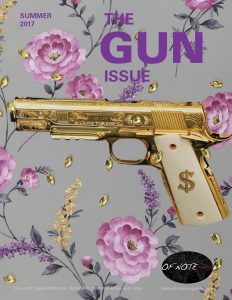

Dollar Billz, from the series Gun Love. © Dawn Whitmore, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

I’m fascinated with how things are marketed toward women to have this feminine shtick . . . They’re always talking about the gun’s sexy lines, the pink color, the slim fit that would fit in your tight jeans. — Dawn Whitmore

BY GRACE ANEIZA ALI | THE GUN ISSUE | SUMMER 2017

In her provocative photography project Gun Love, Washington, D.C.-based photographer and visual artist Dawn Whitmore transforms weapons of destruction into objects of desire. This collection of gun portraits is unapologetically about glamour and bling. What it’s not is a celebration or glorification of gun culture despite how it may appear at first glance.

Encased in gold, bejeweled, bedazzled, imprinted with Hello Kitty stickers, adorned with a breast cancer ribbon, designed with floral prints, embossed with the Louis Vuitton logo, or simply bathed in bright pink, these decorated firearms, intentionally manufactured and marketed for their “feminine mystique” are a striking commentary on a troubling American gun culture and the modern woman.

In what is a layered artistic process, Whitmore sources and prints the images of these (real) AR-10’s from Palmetto State Armory, sets them against elaborate print designs, and re-photographs the combination of gun and background. The result is a disturbing yet compelling beautification of the gun, leaving the viewer entranced by the shiny, glitzy, deadly object.

Gun Love also features staged portraits of women modeling as various characters and holding replicas of the real decorated guns Whitmore found online. Many of the models had never held a gun before. Whitmore gave no directions on how they should pose, only asking the women to portray the stance they felt a woman with a gun should embody. The portraits reveal, according to Whitmore, how a gun can immediately transform one’s sense of power.

Whitmore, who has a background in environmental conservation, was no stranger to gun culture and grew up around a hunting community in rural Maryland. It was a particular kind of hunting of animals that ignited Gun Love. In a controversial strategy that made headlines in 2013, the National Park Service responded to a problem of too many deer in D.C.’s Rock Creek Park that were threatening the park’s ecosystem, by hiring sharpshooters to kill them. Whitmore began making work in response to these “managed hunts” and in doing so encountered images of women hunters, decked out in camouflage outfits or pink gear, full make-up, and posing with pink rifles, or at times, their bloody kill.

Whitmore questioned this growing visual imagery—women with guns dressing provocatively in hunting scenarios. Wondering whether this portrayal of women with decorated guns was coming from a male or female gaze, Whtimore began to formulate Gun Love. She exhibited the project in 2015 as an artist-in-residence at the Arlington Arts Center in Virginia.

We first encountered Whitmore’s work on the cover of Montana Ray’s collection of poems, (guns & butter), which is also featured in The Gun Issue. This Spring, in an interview with Whitmore over Skype, we talked about our culture’s use of women with guns as a marketing tool to sell sex and power.

Pinkie, from the series Gun Love. © Dawn Whitmore, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

GA: First, tell us about these guns. Where do they exist?

DW: I found the images online. There are many different sites where you can send your gun in and the same way you can have your car wrapped in some kind of skin, you can send your handgun and a company will wrap it with flowers, for example. The cover of Montana Ray’s book is a gun that’s been wrapped in a flower shrink wrap.

GA: You take this complicated object of empowerment, of fear, of violence, and architecturally it’s a beautiful machine in a lot of ways, and you feminize it, you glitter and gloss it up. There is something rather uncomfortable yet compelling about this approach. You’re engaging our advertising culture, marketing, consumerism, you’re engaging all of these different ways that we get things “sold” to us. When I look at this work, I question if in making these guns so aesthetically beautiful, you are also stripping it of its power. But, there’s a flipside, too. If we beautify this object, strip it of its power, are we also making it more toyish?

DW: I’m fascinated with how things are marketed toward women to have this feminine shtick. I have tons of gun magazines that I’ve collected that have these advertisements directly targeting women. They’re so absurd. They’re always talking about the gun’s sexy lines, the pink color, the slim fit that would fit in your tight jeans. I stand somewhere between being disgusted by that—why do we have to have sexy guns just because we’re women—but also, as objects they’re fascinating. We like things that look pretty, we like to hang these pretty things on the walls. The people who came to my show in the D.C.-area were mostly anti-gun. But still there was a real attraction to these little images of beautiful guns, which was fascinating to me.

GA: In an interview for the Arlington Arts Center, you were very careful about not aligning the work with a didactic message. What are the messages that you think this body of work conveys?

DW: A lot of my work looks at how women are in various subcultures. We’re giving little girls pink guns and teaching them that this is part of being a woman. I’m just not sure in the long run I understand the benefit of that. When you’re talking about sex and violence, which historically are two oddly human things that go together, to progress we have to be very careful with how we market that. And how we say that’s okay. Because it’s really scary. When you make something pink on a weapon that’s meant to kill, things become associated in different ways in the mind.

I live in D.C. and the Arlington Arts Center is in Virginia, which is very pro-gun friendly. There were some people who came to the exhibition and got aggressive with me. “Oh, so your work is about hating guns,” they said. One woman, who has a line of clothing that’s specifically made for women to conceal and carry guns, wanted to do a fashion show in the exhibit space. I politely had to tell her I didn’t feel comfortable with that.

GA: She read the work in another way . . .

DW: Yes, some people did. The reason I did this show was to open up that conversation. I don’t think sex and violence are talked about enough. This is a hard thing for me, I’m definitely not by any means pro-gun but I do a lot of backcountry outdoor adventuring. I’ve backpacked through Alaska, I’ve been to a lot of places and been in a lot of situations, where not to say that I want a gun, but I do understand there is a place for them.

My argument is that I don’t think they need to be sex-fitted and considered attractive to children and women. You have a tool that’s meant to kill. The point is to kill or to maim or seriously injure. I don’t think we need to take violence into a realm where it should be ‘pretty’ to do so. A lot of my research had to do with women’s guns groups and gun clubs for children. When I was doing the project, I’m sure it’s still the same now, the NRA was dumping tons of money into attracting women and children because they need the next generation of people to market to. In doing so, there was a teeny shotgun that launched for children called “The Rascal” and it came in seven different colors.

GA: This is a real gun…

DW: It’s totally real. You can buy them online. There are gun groups that show little girls with little guns and they are all pink. So, you have all these little girls shooting pink guns and wearing pink. There’s this insanity as to how we’re “sexifying” violence. It makes me insane.

GA: Your work is very layered. You take the gun as an art object and then place it against a feminized wallpaper background. I want to ask where you source the wallpaper from? And then there’s the other layer in the making of the work where you photograph the gun against this background. Can you talk about that making, that artistic process?

DW: I always think of my work as being veiled; you pull away the veils as you move through the pieces. For the wallpapers, I’ve always been fascinated by domestic settings. You have a house, each house has a different tone depending on the decor, specifically if you take everything out of a room and you are left with wallpaper that in itself creates a sense of space. When you have sense of space, how can that set the tone for what you’re trying to do with the wallpaper.

For example, the wallpaper for the gold gun came from an online reference source where I was looking at its aesthetics. I wanted to think what would make [the gold gun] pop. Also, how could I contrast this “granny” setting with this gangster woman’s gun. I love juxtapositions. I love that tension. I have a huge collection of wallpaper images taken from online because at that point I was doing tons of appropriation. All of the guns in the square pieces are real guns that were shown on websites where women were proudly showcasing how they decorated their guns, or how a company decorated them.

Hello Kitty, from the series Gun Love. © Dawn Whitmore, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

GA: Women and girls are being marketed these guns more and more, at the same time, women are dying by gun violence more and more . . . how do we make sense of this contradiction?

DW: At the time, I was finishing up this project, The Washington Post ran an article that the hot selling item to get the woman in your life was a Hello Kitty assault weapon, some kind of Hello Kitty-themed gun. That really made me think about why men are giving women tools that are meant to kill, but decorated as they if they were for a child.

GA: Do you find that this sexualization of gun culture for women is primarily sourced from a male gaze or do you find that women are just as culpable in the sexualization of gun culture?

DW: Both, although I wonder where it originates from. I think women have been vying for power, and I understand how weaponry is one way to meet that.

GA: You made this work with a particular intention: to call attention to our advertising culture and how we market and feminize guns for women and girls. Then a visitor to the exhibition reads the project as a wonderful way to portray gun culture, believes that guns are glamorous and wants your work to be the background of a fashion show to sell more gun products. How do you respectfully respond to that as an artist?

DW: While I don’t agree with the woman who wanted to have that conversation with me, I love the opportunity to talk. I think there’s nothing better than talking to someone about your different values. That is how I believe in change. Even if it comes down to those ‘throw down’ conversations. I have to remember that someone might have come to that reading because they grew up in a place where they were so unsafe that the only way they could sleep at night is if they had a gun, or their parents had a gun. I get that. I can imagine myself being in that role because I’ve spent time in various communities. My goal is always to remain human to people and not look at them as “other.” That’s why I try not to be too aggressively opposed with the project because if I was, I wouldn’t be able to have these conversations.

GA: The increasing visibility of violence against women have also galvanized the women’s resistance movements, for example, organizations like Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense. They’ve partnered with the Women’s March movement to ensure that gun violence against women is a priority. I wonder if you have any thoughts on the particular role for women artists to take on this issue?

DW: I think the nature of being women holds us responsible. I’m not a mother, but when it comes to this idea of wanting to protect, I think women have a ferociousness when it comes to maternal instinct, and this can be one of those opportunities where you somehow tap into that. I think of women and violence, I think of a household with children. My mind automatically goes to children. And children were in a lot of what I was reading: for example, the toddler that picks up the gun out of the handbag and shoots his mother at Walmart.

Cross, from the series Gun Love, © Dawn Whitmore, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

GA: How does our culture justify buying toy guns for children? Yes, it’s a powerful advertising, marketing culture we are fighting. But we as individuals are the ones that still buy it, wrap it, and gift it to a child. Why are we doing that?

DW: These were all things I went crazy about with the project because I tried to understand why. I have no idea. Sadly, how it started in this country is when we played “Cowboys and Indians” and we took an ‘other’ to have power over them, which I think is a really sad root of playing with toys and imagination.

GA: What sets your work apart, which I am sympathetic towards, is the commentary it makes about children, particularly our girls. When we talk about this larger beast of women and gun violence, its effect on little girls is largely absent from the conversation. I see Gun Love and I see you working to ensure that we bring the violence done to girls into this conversation.

DW: That was a very important launching point for me. The television show 20/20 did this great special episode where they talk about little girls, guns and the NRA. It’s a sick world of trying to get children enraptured with pretty guns in bright colors.

GA: The irony here is that the marketing is more and more directed to these young girls, but the violence they’re fighting back with these guns is male violence—rape, intimate partner violence, domestic violence. In other words, men are marketing guns to women to protect them from men. Here is another example where women, not men, are held responsible for male violence.

DW: When you pick up these gun magazines and you find the ads that are targeted towards women, oftentimes it’s a man lurking behind a woman’s shoulder or she’s in her house. It’s being directly marketed toward that [male violence], which is really fascinating, that the general population can’t see through the problem. Men are telling you that you need your gun because of male violence. . . and at the same time, we’re going to make a couple bucks off you to protect yourself.

GA: Many of artists in The Gun Issue have experience with gun violence and so their artmaking and activism come from a deeply personal place of trauma. I read that you didn’t have this particular experience although you grew up in a hunting culture in rural Maryland. But a lot of our artists have, either they lived in heavily-violenced neighborhoods or someone they loved was the victim of gun violence and that’s how they came to take on this issue. What I appreciate about your point of entry into this subject is that you didn’t need a personal experience with gun violence to be passionate about using your artistic practice towards engaging it.

DW: Not at all. I feel very fortunate that I haven’t. I think that’s because I have a very empathetic connection to those who have. As I was reading those stories, I don’t need to have those experiences to imagine what that pain must be like.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

♦

Grace Aneiza Ali

Grace Aneiza Ali is the founder and editorial director of OF NOTE Magazine. She is also a faculty member in the Department of Art Public Policy, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University.

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change.

OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.