New York | Talking Back To Street Harassers: An Interview with Artist Tatyana Fazlalizadeh

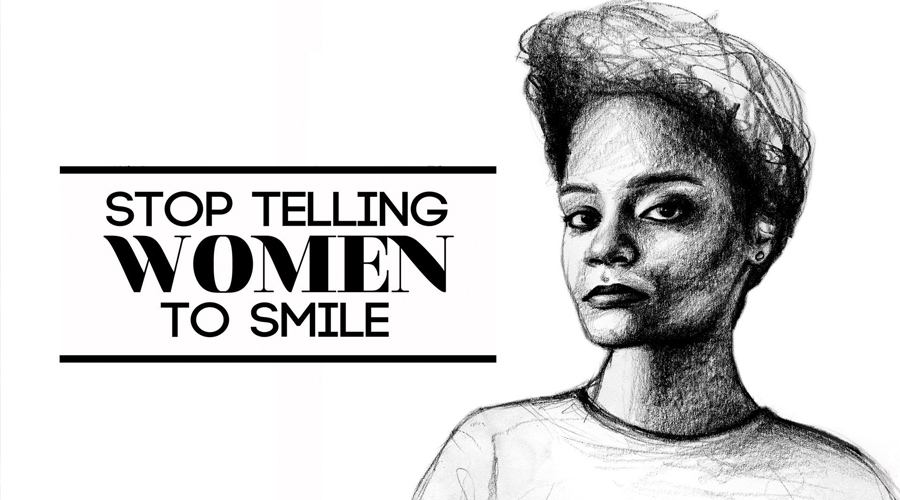

Image courtesy of Stop Telling Women to Smile.

BY JAIMEE A. SWIFT | THE GIRLS ISSUE | SPRING, 2013

Hey, baby! You’re looking real good in that dress!”

“Why aren’t you talking to me — I said, hello!”

“Smile, woman! You’d look prettier if you did.”

Irrespective of geographic location, race, age, language, sexual orientation and culture, thousands of women and girls experience street harassment.

According to the nonprofit organization Stop Street Harassment (SSH), street harassment begins around puberty. While street harassment is most frequent for teenagers and women in their twenties, the chance of it happening never goes away.

Street harassment is a human rights violation because it limits a person’s ability to be in public–especially women’s–and includes unwanted whistling, leering or sexist, homophobic, racist and transphobic slurs; persistent requests for someone’s name, number or destination after they’ve said no; as well as sexual names, comments and demands, following, flashing, public masturbation, groping, sexual assault and rape.

There is one woman, however, who is leading a revolutionary art-infused platform to combat street and sexual harassment. Artist Tatyana Fazlalizadeh is shattering these culturally embedded, misogynistic behaviors by encouraging women and girls to stop accepting street harassment; telling men and boys to stop believing that they have autonomy over women’s and girls’ bodies, feelings and emotions; and informing men that they need to stop telling women to smile.

A Brooklyn-based painter and illustrator, Fazlalizadeh is the creator of Stop Telling Women to Smile, a traveling visual art series that uses the power of art to end street harassment and promote gender equity and female empowerment.

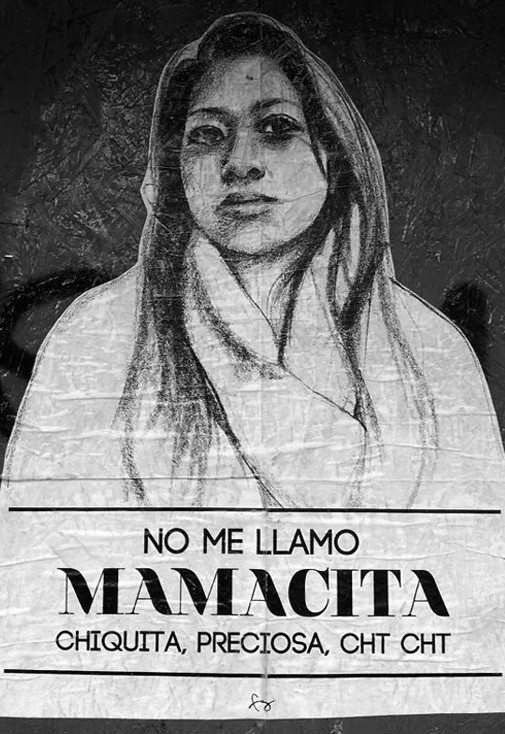

First seen in Brooklyn in the fall of 2012, her portraits of women, composed with captions that speak directly to offenders outside in public spaces, can now be found in various locations, including Mexico, Germany, Canada, France and the United Kingdom. Taking women’s voices and faces, and putting them in the street, Stop Telling Women to Smile creates a bold presence for women and girls in an environment where they are so often made to feel uncomfortable and unsafe.

In honor of International Anti-Street Harassment Week, I chatted with Fazlalizadeh on why she started Stop Telling Women to Smile and how art, activism, and advocacy are essential to social justice.

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, creator of “Stop Telling Women to Smile.” Photo courtesy of Stop Telling Women to Smile.

Q: You hear about tragic incidents such as Mary Spears who was shot in Detroit after denying a man’s advances or Janese Talton-Jackson who was also shot in the street just because she said “no” to street harassment. Did these examples of gender-based violence inspire you to start this project?

A: Those were incidents that were a huge part of the project. When I started this project, I wanted to talk specifically about everyday street harassment and how I was treated outdoors on the street and the way that my friends, family members and colleagues were treated out in the street by men. And those incidences really range from smaller, more insidious moments like telling a woman to smile to actual physical violence and assault.

I think that talking about these smaller micro-aggressions that women see every day and the smaller oppressions that go unnoticed or are unassuming to the general public are important. Calling a woman “sweetheart” or “honey” or telling a woman to smile–all of these things are normalized and accepted as small moments that are not a big deal.

With this project, I was trying to point out that these moments are a big deal, and they also influence these dangerous instances of women actually being killed and assaulted by men because men feel entitled to their bodies. In doing this project and traveling with this project and meeting so many women and listening to their experiences, [it’s] really what composes the project as a whole. It really brings it all together when we talk about violence against women–whether it is verbal or physical–and how it is all related to street harassment.

“My name is not mamacita, little girl , precious, or ‘cht cht.’” Image courtesy of Stop Telling Women to Smile.

Q: Was there a specific instance of street harassment that you experienced that helped catalyze this project as well?

A: I get that question a lot but there was not a moment or an instance of street harassment that happened to me that sparked this project. I can’t think of just one instance of being harassed in the street that made me want to do this series. It was just the fact that it happened to me all the time. It was just this burden that I had to endure and carry in everyday life. Whether or not I am actually harassed today, tomorrow or yesterday, it is the threat of being harassed that is always there. I know that every time I walk outside of my house, I know that it could happen to me, and it is likely to happen to me because it has happened to me so many times throughout my life since I was a preteen.

This is a burden I carry and that so many women do as well, I think that alone is enough of a reason to start a project like this. I was always thinking about it and I always wanted to address street harassment in my work. Over the years, I just didn’t do anything until this idea came to me and it was perfect.

Image courtesy of Stop Telling Women to Smile.

Q: You are a talented oil painter, illustrator and muralist. How did you get into art? Why is it important to use art as a means for social activism to address violence against women?

A: I decided to pursue art as a career later on in high school when I was about to graduate, and I moved to Philadelphia from Oklahoma City to go to art school. I really started to find my voice in my art and my skill and what I wanted to say with that art. I think that having the skill to create beautiful paintings and drawings is great by itself but coupling that with a strong message and a strong purpose, it really becomes that much more powerful. So, I think that using art as a tool for change–for political and social change–is really important. I think that digital art has a particular advantage in the way people relate and react to it. It’s very visual, urgent and immediate when you see an image, relate to it, consider it and think about it. That is what the Stop Telling Women to Smile project is doing–it’s art in the street. You walk by it, you read it and you are going to have some type of reaction to it.

I want men to be kind of taken aback. I want them to think and consider it. I want women to see the work and be comforted. It is so powerful in that way and as an artist, to use my work to react to something, say something and for it to be useful in some way. I chose to use my art in this activist role–as many artists do–and that is totally fine. But I also chose to do my art to be useful to folks.

The project’s art sometimes receives backlash. Pictured here is art that has been defaced. Image courtesy of Stop Telling Women to Smile.

Q: Stop Telling to Smile has been featured in countless cities in the U.S, and in other countries such as France and Mexico. What has the reception been like to the project? Has there been any backlash?

A: Yes, for sure, I have faced negative backlash. I don’t even think my work is too controversial or confrontational, but it is. You would think that saying ‘stop telling women to smile’ would be encouraging, but people get really upset with this work–men in particular–and react in a negative way. Much of the work is defaced, torn down or drawn on with very crude imagery. People do have strong reactions to it and a lot of these reactions are not positive. And you know, I am okay with that. It’s great for me to see that people are looking at this work, they are doing something and they are being challenged. That for me is good because it is making them think about their behavior and it is challenging them to change their behavior.

The reception from women has been positive most of the time, but I also get negative reception from some women as well. Many women are grateful and supportive, and that really overpowers the negative criticism. Not everyone is going to like this work, and they are not supposed to. If everyone agreed with my work, there would be no reason to see it. We have to challenge them because otherwise nothing is going to change.

Q: Why do you believe that street harassment is so pervasive? How can we stop street harassment and violence against women?

A: It really comes down to men feeling entitled to women’s bodies. And honestly, I wouldn’t just say it is men; it is people in general feeling entitled to a woman’s body. For so many reasons, women aren’t seen as full people, full human beings with a wide range of emotions with autonomy over themselves. We are seen as bodies; decorations for men. Men are outdoors because they are going to work, going to school and because they have a business, but women are expected to be pretty for the men outdoors. It is as if women are here to entertain and to please men. That is why whenever we dress a certain way or wear certain things, it is taken as if we are doing it for the male gaze or doing it for the pleasure of men. And this is why you have pervasive rape culture or victim blaming, where people are excusing the behavior of men and blaming women for what they are doing.

We have to talk about street harassment and these micro-aggressions that women and girls face in any environment–whether it is on the street, at work, home or school. We have to talk about what we go through every day–even if it seems silly or small or trivial–because it is not silly or small. We need to talk about how women’s bodies are consumed and how we are treated as objects, and not people who have control over our bodies to our own lives.

Street harassment happens every day and that is why we need to continue the conversation because it really and truly affects women and girls.

A version of this interview was first published in SAFE Magazine.

♦

Jaimee A. Swift is a Washington, D.C. based writer/activist who is passionate about social justice. You can follow her on Twitter @JaimeeSwift.