Guyana/India | Gaiutra Bahadur Charts the ‘Coolie’ Woman’s Odyssey

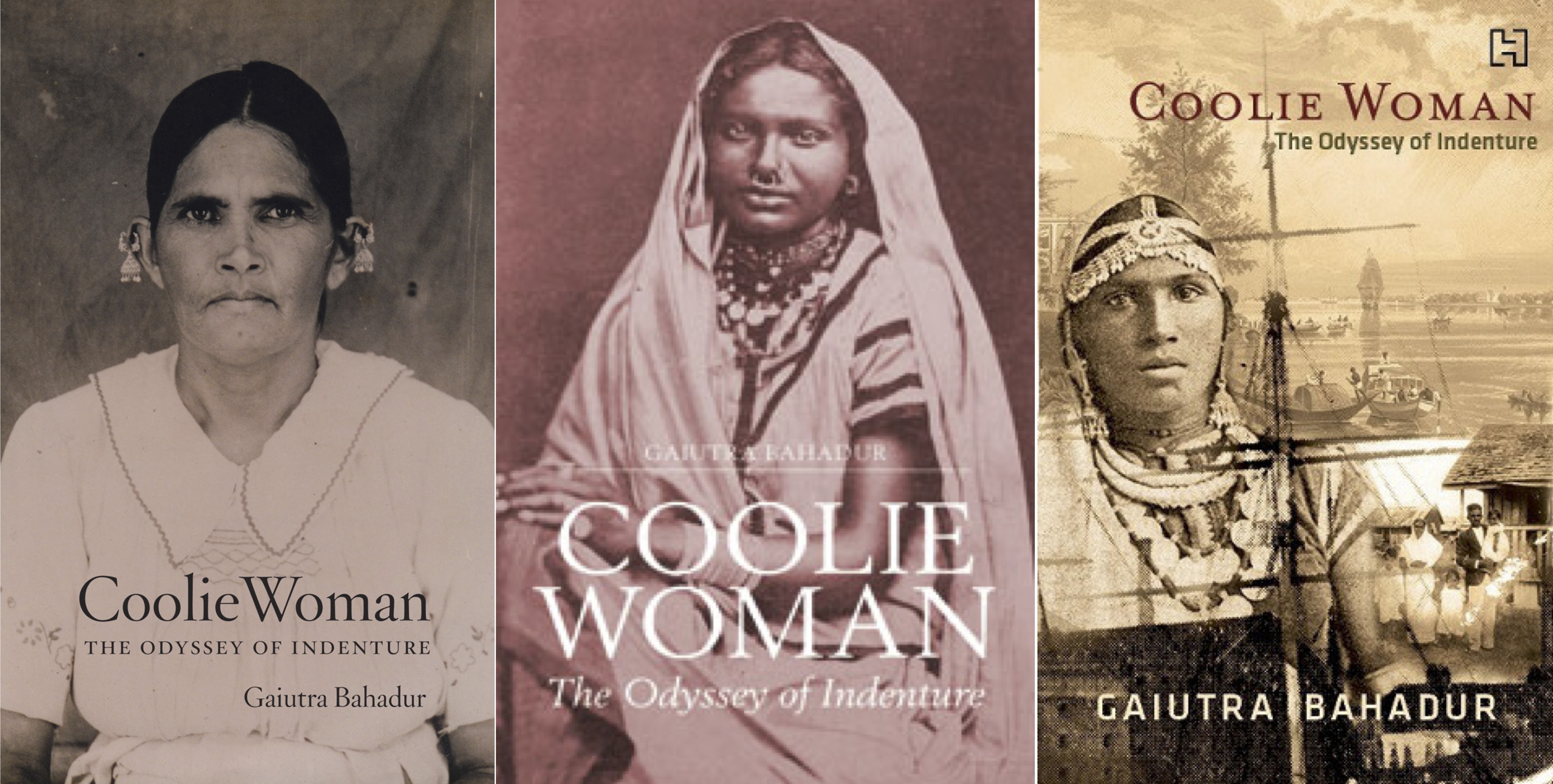

Cover art depicting Indian indentured immigrant women for the US, UK, and India editions of

Cover art depicting Indian indentured immigrant women for the US, UK, and India editions of

Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture by Gaiutra Bahadur.

My entire life has been built around the structure of having left one place for another as a child. It has determined choices I’ve made for a career. Obviously, it’s had a huge psychological impact. There is no way for me to escape that identity. But at the same time, I can shape it to mean what I want it to. I am an immigrant, but I’m also a journalist, I’m also an author, I’m also a sister, a daughter. I’m all of these things at once. —Gaiutra Bahadur

BY GRACE ANEIZA ALI | THE IMMIGRANT ISSUE | SPRING, 2014

In my classroom, I charge my students to be the bearer of questions more than answers. At times our questions—what we question and why—are more profound than our answers. Gaiutra Bahadur’s Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture is pregnant with questions, profound and equally haunting. And fittingly so. The saga of what a quarter of a million ‘coolie’ women endured as they left India for the Caribbean under the British system of 20th century indentureship requires interrogation and accountability. To excavate the stories of these women, Bahadur bravely turns inward to her own family. She charts the journey of her great-grandmother Sujaria who embarked on her own ‘middle passage,’ alone and three months pregnant, for some dream of a better life. However, what she met in Guyana in 1903 (then British Guiana) was a burgeoning culture of violence, sexual exploitation, and harsh labor. And yet, Sujaria’s story is not a single, one-dimensional story of victimization. Instead, Bahadur finds the triumphs, cunning, and resilience in these women.

Early this spring, I met Bahadur at the New York Public Library on 5th Avenue to talk about the ‘coolie’ women in our lives. We are both Guyanese-born women, carrying with us the legacies of our Indian indentured great-grandmothers as we ourselves move about and navigate the world. While Bahadur has been able to trace and unpack the story of Sujaria, for most Guyanese women like myself, our great-grandmothers’ stories remain mysteries. For now, Bahadur’s poignant telling of Sujaria’s story is a balm for the absence and longing many of us still know.

.

When I think of you in the process of writing this book, I think of an artist, of a visual painter—writing it and setting it aside and coming back and editing and repainting and making missteps and leaving it alone and coming back. Do you think of this book as—maybe not in a traditional way—a work of art?

Initially, I did not, because I come from a daily newspaper background, and I think daily newspaper reporters are for the most part, pretty humble about what it is that they do. In the beginning, although this is such a personal story, I did approach it as a reporter might, and I dealt with the archives as an investigative reporter might. But in the end, there was really no way to tell the story without being creative and imaginative. That’s because there were so many limits to what the archives could give up, and I had to think about alternative ways of telling the story, such as using these strings of questions.

I actually took inspiration for that from a New Yorker podcast, a short story by Donald Barthelme, “Concerning the Bodyguard.” It’s a short story but written almost entirely in questions. It’s told from the perspective of a bodyguard in an unnamed Latin American country, probably a dictatorship, and so this mode of questioning, of speculating, sort of puts you in the center of his own uncertainty about the world and what people in it might represent. He’s protecting some important figure. I heard that and I thought it might be a solution to dealing with the limits in the archives: if I could write questions in that way, questions that weren’t just vague admissions of not knowing, but ways to advance the plot and to provide detail and convey feeling. So, I guess, yes, in the end, it is to an extent a work of art, because it uses artistic techniques. Whether it succeeds or not is up to other people.

I also used the technique of Ekphrasis. It’s a form of narration through descriptions of art. You probably noticed that I used a lot of photographs and descriptions of photographs in the telling of the story, which I think sort of elevated it in some sections to creative work.

An indentured woman in Trinidad, circa 1890. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

An indentured woman in Trinidad, circa 1890. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Was that also a way for you to evoke memory?

Absolutely, I use a lot more archival images, and it was a way to imagine those places in the times that I obviously wasn’t there to witness them, but also to interrogate the history. There’s a particular photograph of overseers in front of the Demerara plantation, and I use it in a cheeky way to ask questions about those particular men and what their interactions were with women on the plantations. I use art, I mean if you consider archival images art . . .

I do!

I do as well. I think that also helped take it to another level—the technique of using questions in a creative way and the use of photographs, certainly. Just to add to that, the ways in which the themes of the images came together so beautifully on their own, the way I describe migrating in the beginning as kind of a dismemberment, I didn’t realize that would echo as hauntingly as I think it does when I later write about what happens to women who are victims of cutlass attacks. It was almost as if there was this grand plan. I don’t want to be too spiritual, that’s not what I mean, it just all came together quite naturally.

It is very intimate. I think that’s what I’m really drawn to about the book, but I’m not the most objective because reading your story is like reading my own family’s story. Did you always know you were going to position yourself in Sujaria’s story or was that a decision you made somewhere along the way? If so, what was the catalyst for that decision?

Well, initially I did not want to be a part of the story or a very big part of it in any way, because, as I said, I was approaching it as a reporter does. And it just so happened that I was reporting my own history. There was some debate when my agent was shopping the proposal around. There were publishers that wanted it to be more personal. And there were publishers that wanted it to be less personal. It took a year to sell this book, perhaps longer. So I had a long time to think about what wasn’t working in pitching it. Through feedback from friends who know me really well, I decided I needed to be more present in it. In a way, adopting this mode of “The Journalist” was not being fully honest with myself. It was maybe an expression of fear because it’s a very hard history to confront. It’s a violent history, it goes to the core of who I am, and all the issues that we still struggle with. My friends gave me good advice and encouraged me to be a little braver. And I think you can see the fear in the writing. The last chapter, which is about violence against women in Guyana today, begins with me. I just didn’t know how to write that chapter. I tried, and I tried, and I tried. I had to stop many times. I was uneasy about it. It was a subject that I did not want to look at directly. So, in the writing of it I incorporated that fear and that was the way I was able to start talking about it. I wanted to avert my eyes. I don’t know if you remember the beginning of that chapter, but it’s about wanting to look away.

That’s one of the things that I found really remarkable, the full-circle moment, the violence against women. I didn’t want that to be the full-circle moment. I want things to have evolved and changed. But the way you paint it was so saddening, to see that so many years have passed, and we’re still kind of there.

Many people do not like the end, including my parents. They thought it was far too depressing a conclusion. One of the peer reviewers with the University of Chicago press, who is anonymous, thought that the book ought to end at the ninth chapter with the return to India. That’s a much more triumphant narrative. He said everything after that was anti-climax. Obviously, I disagree. I think that everything after that is what we need to confront. Because this isn’t just the circular narrative of leaving India and returning to find yourself, find your roots. It’s a lot more complicated and interesting than that.

Sujaria gets on the ship to seek out a better life, at least that’s the story she is sold, that the then British Guiana is a land where she can make a little bit of money, save up that money, and go back to India. Today we have this mythical quest for the “American Dream.” Everyday people from all over the world get on planes and boats and ships and cross fences and borders and oceans illegally or legally to come to the United States. My mother did that. My mother got on a plane with three children and left her homeland for the unknown. That’s brave, that’s remarkable—what women are doing every single day to come to this country. In thinking about full-circle moments, do you see parallels between Sujaria’s journey as an indentured immigrant to Guyana and our current 21st century definitions of the immigrant?

I absolutely do. There’s been a feminization of migration. I think for the first time there are more women than men migrating globally. Immigrants who end up in the U.S. from, whether it be China or Mexico, often find themselves in really exploitive situations that are akin to indentured labor. The same question is raised about choice versus being exploited, agency versus a new form of slavery. The questions are still very much the same. In terms of contemporary parallels. A piece I was working on for The Nation had a little bit to do with sex-selective abortions and the shortage of women in particular parts of India, which is the result of decades of families preferring sons to daughters and aborting female fetuses. Now they’re dealing with it, because men are having a hard time finding women to marry in certain parts of India. And as a result, women are being possibly trafficked from one part of India to another and exposed to a lot of harm as well. There’s a lot of violence against women that results from this whole process. That is the story of ‘coolie’ women as well—how a shortage of women can create opportunities but more often than not, it doesn’t increase women’s value, it just exposes them to greater violence.

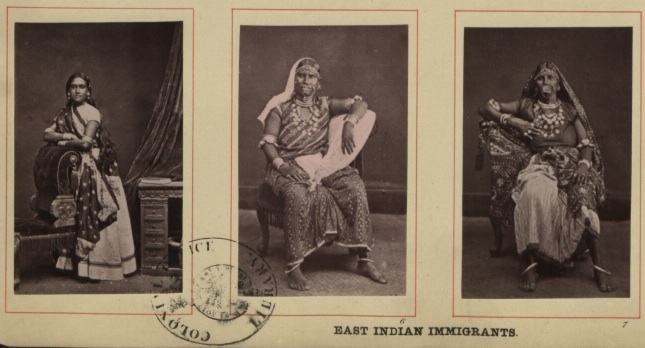

East Indian Immigrants, British Guiana, 1870-1931, The National Archives, United Kingdom.

East Indian Immigrants, British Guiana, 1870-1931, The National Archives, United Kingdom.

You write these beautiful lines where you pose the following questions of your great-grandmother:

“Was she a victim? Was she leaving this country out of some act of desperation, or was this really an act of activism? Was this really an act of her choosing her own destiny?”

I really thought about those questions in a 21st century context and how we think about and frame the immigrant. Are they merely just fleeing or are they doing something incredibly brave and heroic, which is being in charge of their own destiny and believing in the notion that they are free to move about the world?

Right. Or, both? I think the answer for Sujaria was in between. For a lot of immigrants today, I think the answer is also in between. I’m sure they’re fleeing desperate situations in their home countries, economically or, in some cases, politically. So, there is that push-factor operating. There’s also this incredible will. You talk about your mom getting on a plane with three children and coming here. My parents made that same journey, too. I just have the utmost admiration for their strength and their will to make and remake a life for themselves.

What I find fascinating are the objects that our families choose to bring over in their suitcases. My mother made sure she packed the pots. The pots! In America, would there be no pots? In her mind, things like the karahi and tawa were the important things to bring.

My parents were given, for their wedding, a pot to make dahl in and they brought that to the United States. It has lasted us for over 30 years then it just fell apart.

Are there modern day ‘coolie’ women? I mean the labor part of the definition of being a ‘coolie’ woman—leaving your homeland, seeking out a better life, signing up for some kind of arrangement?

Yes, that kind of semi-forced labor happens still. If you look at South Asian migration to the Gulf, a lot of those workers could be seen as indentured workers. I know that doesn’t address the gender part of it, but it’s an ongoing system that immigrants, including women, find themselves in.

How do you define the immigrant? What’s your definition? Both personally and politically?

Well, I mean, it’s hard to know how to answer that, except in an abstract, theoretical way, and I hope that’s an OK framework. I think of the immigrant as sort of the harbinger of globalization to an extent. For centuries, immigrants have been doing what it is that we seek now, which is to be comfortable in multiple spaces at once. They’re used to doing that, to not being wedded to a particular location or a particular set of contacts. They’re used to having their social capital entirely decimated and having to build it again. So they have qualities of resilience and flexibility and adaptability and being able to operate in multiple contexts at once that we kind of celebrate in the global citizen.

I was thinking of how the media has been framing Lupita Nyong’o and I’ve yet to see “immigrant” as a prominent identifier for her. And she’s been very vocal and proud of her Mexican-Kenyan heritage. But when the media gets a hold of her story, nobody’s saying “immigrant.” I find that really interesting if not problematic.

So when they, when the media says “immigrant” they are trying to evoke someone who is part of the huddled masses rather than individuals with their own trajectories and achievements?

Right. Or somebody that fabulous, impressive and phenomenal would be diminished if we called her an “immigrant.”

Well, my entire life has been built around the structure of having left one place for another as a child. It has determined choices I’ve made for a career. Obviously, it’s had a huge psychological impact. There is no way for me to escape that identity. But at the same time, I can shape it to mean what I want it to. I am an immigrant, but I’m also a journalist, I’m also an author, I’m also a sister, a daughter. I’m all of these things at once.

THIS INTERVIEW HAS BEEN CONDENSED AND EDITED.

♦

Grace Aneiza Ali is the founder & editorial director of OF NOTE magazine. Grace was born in Guyana, South America and immigrated to the United States when she was fourteen years old. Guyana continues to inform her worldview. www.ofnotemagazine.org/grace-aneiza-ali. Twitter: @ofnotemagazine

Grace Aneiza Ali is the founder & editorial director of OF NOTE magazine. Grace was born in Guyana, South America and immigrated to the United States when she was fourteen years old. Guyana continues to inform her worldview. www.ofnotemagazine.org/grace-aneiza-ali. Twitter: @ofnotemagazine

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change. OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.